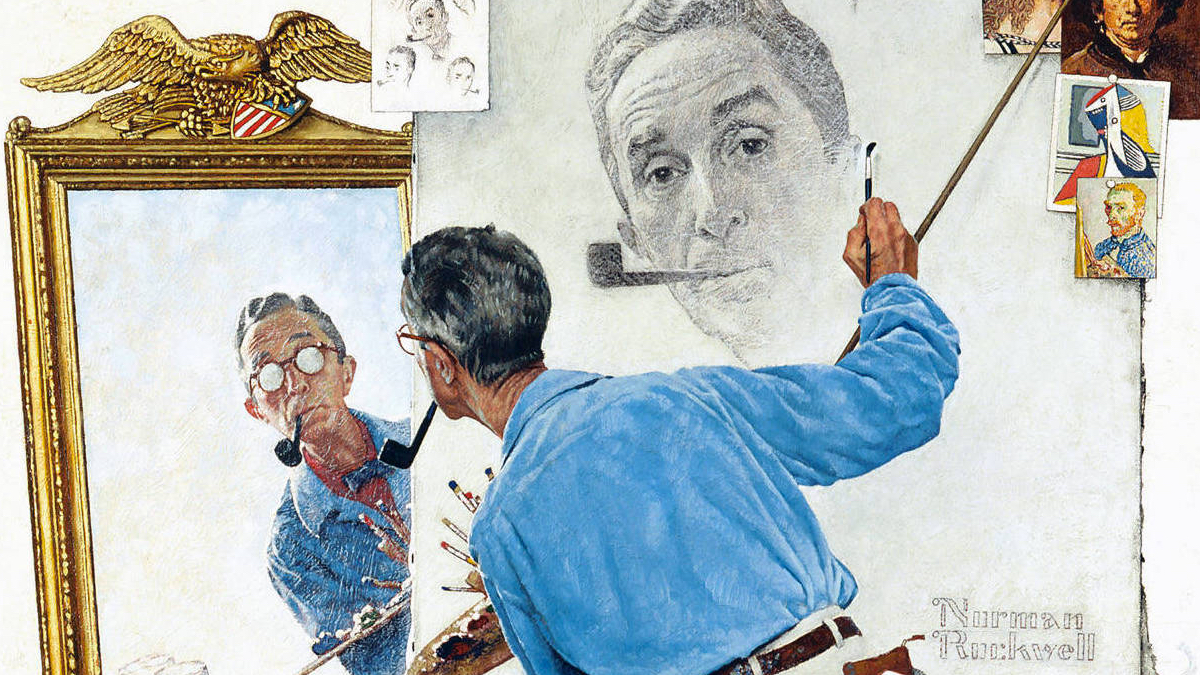

10 Things To Know About Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell is surely the most famous American press illustrator in the world. Born in New York, 1894, and died in Massachusetts, 1978, he is rightly called the “storyteller” of America. Indeed, his works trace the history of the United States in the 20th century. Known for having produced hundreds of covers for The Saturday Evening Post magazine, he is less well known for his talents as a painter. Indeed, each of his illustrations was previously executed in the form of a painting. Discreet and not seeking notoriety, he said little about his life and activities. Artsper has investigated; discover 10 anecdotes about the most famous American illustrator in this article!

1. He’s a drawing genius

Very early on, the young Norman Rockwell shows a predisposition for drawing. He wants to become an artist. That’s why, at the age of 14, he entered the New York School of Art. Two years later, in 1910, he left the school to enter the National Academy of Design. He received his first commission: the illustration of four Christmas cards. In 1912, he became a student in the Art Students League. That same year, at only 18 years of age, he was chosen to illustrate Carl H. Claudy’s book, Tell Me Why: Stories about Mother Nature. Even before he came of age, he was the art director of the official magazine of the Boy Scouts of America. In parallel, he illustrated many other youth magazines before joining the Saturday Evening Post at the age of 22 for 47 years.

2. He’s an avid scout

Norman Rockwell was, throughout his life, very involved in the American scout organization, the Boy Scouts of America. As early as 1912, he was commissioned by the latter to illustrate the Boy Scout Hikebook. His work is particularly appreciated, Rockwell was offered a position as a permanent employee to illustrate the weekly magazine, Boy’s Life. Six months later, he was promoted to art director. Although he left the magazine in 1917, he continued to produce illustrations for the Boy Scouts’ annual calendar from 1925 to 1976. These 64 years were his longest collaboration. As a token of his recognition, the organization awarded him the Silver Buffalo Award, the highest distinction for adults, in 1939. Once a Scout, always a Scout!

3. A hard-working perfectionist, he is a representative of Hyperrealism

As a true narrator, Norman Rockwell gave a crucial importance to every detail of the script he sought to represent on his canvas. Indeed, as an illustrator, he had to ensure that the images best reflected the texts. This meant a long technical process. To be as close as possible to reality, the artist had models pose in his studio, not knowing how to paint from his imagination alone. Later, he used photography so that each element (object, landscape, character, or facial expression) would be represented as realistically as possible.

He used all this material to make a very precise charcoal drawing. This initial sketch was then projected onto an architect’s paper vertically on an easel, using a Balopticon, a sort of projector. After transferring it to the paper by drawing the outlines, the photographs themselves were projected. He then replaced the first sketched figures with the outline of the photographic elements. Once this first composition was completed, he would start again from the beginning, drawing in more detail, perfecting the tones and lighting.

To transfer the final sketch to the canvas, Rockwell either used tracing paper or projected his photograph. For the pose of the painting, he would refer to a study, often done at the beginning of the creative process, in color and the size of the intended reproduction, but much less precise.

A labor of love…

Extremely demanding, he could spend several long days on a single illustration, reworking the same section of a composition several times. The finished work was sometimes even discarded. In addition, he regularly asked his entourage to criticize his work, especially to ensure the clarity of his narrative. His style, more precise than one of the naturalist painters, foreshadowed photorealism. This movement consists of reproducing a photograph in the most realistic way possible.

4. A patriot, he participated in the war effort by putting his art at the service of American propaganda

It was not without difficulty that Norman Rockwell enlisted in the Navy as early as the First World War. Indeed, after a first refusal because of his small weight, he was finally recruited. Serving the army as a military artist, he was responsible for his base newspaper.

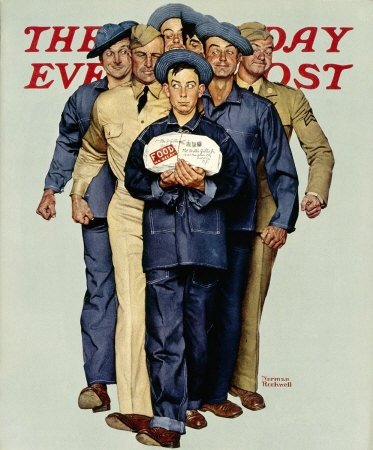

In the early 1940s, he returned to the service of his nation, pencils, and brushes in hand! Aware of the power of the press over the population, he recorded in his covers for the Saturday Evening Post the life of American society during the Second World War. However, they still show optimism and hedonism. Indeed, Rockwell wished, through his images, to maintain the morale of the population and to encourage it to take part in the war effort, in particular by buying war bonds or enlisting in the army. His character Willie Gillis, who was particularly popular, contributed greatly to this. He was a typical young American soldier with whom young boys could easily identify. Harmless and candid, but highly willing and motivated, he is never portrayed in combat or in danger. In 1946, he had his “happy ending” back in his homeland.

However, beyond his activity as a press illustrator, Norman Rockwell worked directly with the State. In 1942, at the request of the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps, he produced a poster depicting a gunner in need of ammunition. Intended to be distributed to ammunition factories, it was intended to encourage production.

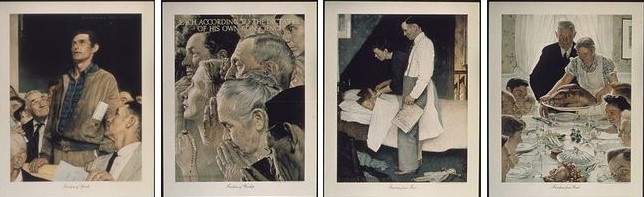

5. His iconic work, The Four Freedoms, almost didn’t see the light of day

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt gave a famous speech to Congress. He set out his vision of the post-war world based on four freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, and freedom from want and fear. Wishing to become more involved in the war effort and inspired by the speech, Rockwell wanted to illustrate these four freedoms in order to make them understandable to everyone. He proposed his idea for posters to the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps. However, in the absence of sufficient resources, the U.S. Army declined the offer. According to some, the American administration actually wanted to use well-known artists to fuel its propaganda rather than an illustrator.

Anyway, Rockwell is not ready to give up his project and he decides to submit it to the editor of the Saturday Evening Post. The latter accepts and, in 1943, they are published on the cover of the magazine. Their success is phenomenal! The government then backtracked and proposed a partnership with the Post to mount an exhibition across the country. The purpose of this exhibition was to promote war bonds and stamps. Indeed, for each bond acquired, a print of the four paintings was offered. It was the most successful war bond sales campaign during the war. In addition, the U.S. Office of War Information decided to print four million sets of the paintings. Combined with the slogan “Buy War Bonds,” they were widely distributed in public institutions. With his masterpiece, Rockwell gave press illustration its letters of nobility!

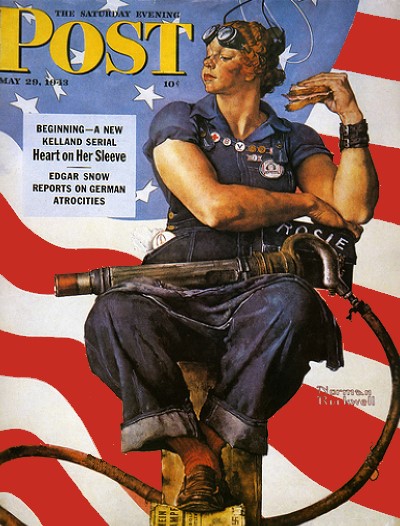

6. He created one of the most famous icons of feminism

Patriot, that doesn’t make Rockwell conservative! On the contrary, he adapts to changes in society and its modern mentality.

During the Second World War, he is aware that war is not just a man’s business. He created the character “Rosie the Riveter” for the Saturday Evening Post. Very muscular, the young worker in overalls tramples on Mein Kampf. An imposing riveting gun rests in her lap. To create this strong image, Rockwell actually found his inspiration in the figure of the prophet Isaiah painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Above all, Rosie evokes the figure of the Virgin Mary! Auréolé, her face stands out against a background of stars, without forgetting her blue working blue which echoes the blue dress of the Blessed Virgin. Thus, Rockwell illustrates that all women, even housewives, had their place in the mobilization of the war effort.

From a patriotic icon to a feminist icon, she became a symbol of independence, which was taken up many times by women’s rights movements.

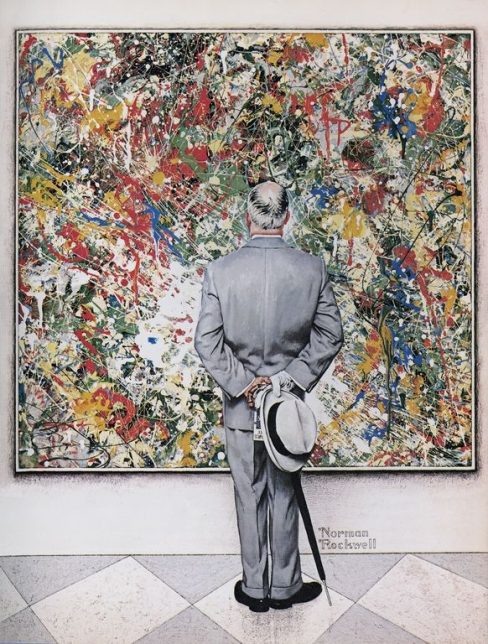

7. He’s long been discredited by the art world

During his lifetime, Norman Rockwell was not recognized as an artist in his own right, but only as an illustrator.

His style was referred to as “Rockwellesque”, often in a depreciative sense. Depicting an idealized and sentimental, even romantic “American way of life”, he was criticized for his particularly approving gaze of his fellow countrymen. Some critics described him as a “bourgeois”, “kitsch” painter to highlight the superficiality of his creations.

Yet Rockwell’s talent for touching the viewer is undeniable. Also, by paying more attention to it, his images seem to carry within them the second level of reading. Indeed, he manages, by the intelligence of his narration, to implicitly tackle more serious problems. Changes in society, the social pressures weighing on youth, the daily difficulties of the working class, and finally racial segregation are all subjects that are evoked. More particularly at the end of his career, he addressed deeper themes, notably concerning the Civil Rights Movement. It is only from this period onwards that his painting began to receive more consideration.

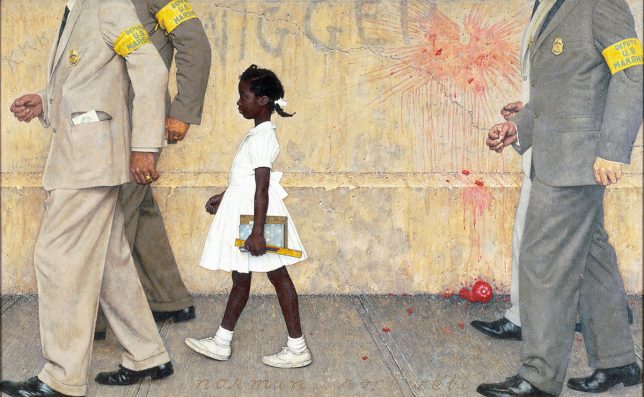

8. He supported the Civil Rights movement

In the 1960s, Norman Rockwell joined the Look magazine. He then had more freedom than in the Saturday Evening Post to express his political convictions. His first contribution was significant for the new, more committed tone of his illustrations. It is the work The Problem We All Live With (1964). It depicts the little African-American girl, Ruby Bridges, on her way to her recently de-racialized school. The presence of four police officers escorting her and a tomato thrown at the wall reveal the threat to the child. The image is profoundly bold for its time. Indeed, the United States was divided between, on the one hand, a persistent segregationist mentality and, on the other hand, the rising demands of the African-American community.

The magazine received as much praise as criticism from its readers. These did not prevent Rockwell from continuing to support the Civil Rights Movement. In 1965, the illustration Southern Justice approaches the murder of 3 militants of the Civil right movement by the Ku Klux Klan. Then, in 1967, in New Kids in the Neighborhood, he again focuses on the desegregation of the United States through the world of childhood and sketches the hope for greater tolerance and social mixing in future generations.

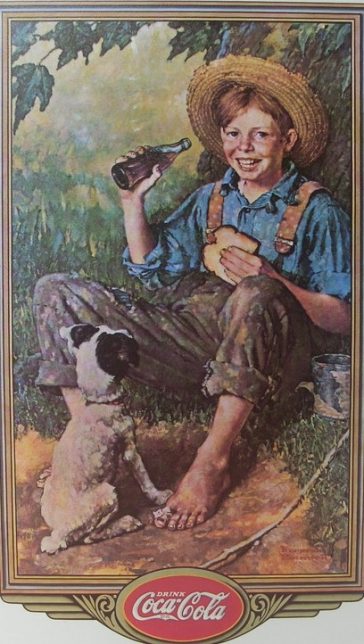

9. He is also a great publicist

Rockwell is much less well known for its advertising. However, many brands asked him to boost their image or sales. Campbell’s Tomato Juice, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, Ford, General Motors and Pepsi, to name only the most famous, have placed orders with him. He has also worked no less than 6 times with Coca-Cola. After his death, his influence in American popular culture was such that in 2015, the Butterball Group, a poultry producer, reused the painting Freedom From Want, from the Four Freedoms series, on its Thanksgiving turkey packages.

In addition, he has also produced posters promoting movies and covers for novels and music albums. Prolific and varied, his artistic heritage is not limited to his work for the written press.

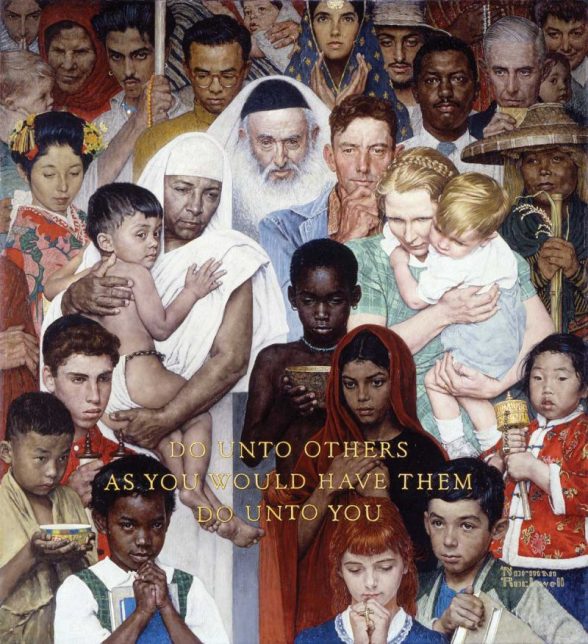

10. The Mosaic The Golden Rule of the United Nations is a rework of one of his illustrations

In 1985, First Lady Nancy Reagan, in the name of the United States, offered a mosaic to the United Nations for its 40th anniversary. The mosaic depicts a multitude of characters from different ethnic, religious, and cultural backgrounds, embodying the world in its universality. In fact, the mosaic is directly inspired by one of Norman Rockwell’s paintings, entitled The Golden Rule from 1961. The title refers to the fundamental moral rule, called ethics and reciprocity, set forth in all major religions. Thus, by writing in gold letters “Treat others as you would have them treat you,” Rockwell wanted to convey a message of peace among men in these times of Cold War, Vietnam War, and colonial independence.

However, as early as 1952, the illustrator had planned to create a painting in honor of the United Nations, called We the People. Finding the subject too pretentious in the end, his sketch was never transferred to canvas. In the end, without knowing it, the artist still contributed to pay tribute to this great institution!

In conclusion

To cut a long story short, Norman Rockwell is the emblematic figure of the golden age of the illustrated press. Despite a style described as hyperrealistic, the success of photography in the 1960s precipitated the end of his career. Able to represent the strengths and weaknesses of the Americans and defending great causes, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom a year before his death, in 1977. By the highest civilian decoration of the United States, President Gerald Ford wanted to thank him for his “living and loving portraits of our country”.

Although his overly empathetic treatment of his subjects was criticized and delayed his recognition by the art world, the Guggenheim Museum eventually organized his first retrospective in 2001. Since then, his works have sold for millions of euros. His painting The Problem We All Live With was exhibited at the White House in 2011 when Barack Obama received Ruby Bridges. Today, Norman Rockwell is no longer just recognized as an illustrator by his peers and the public but is well regarded as one of America’s greatest painters.

About Artsper

Founded in 2013, Artsper is an online marketplace for contemporary art. Partnering with 1,800 professional art galleries around the world, it makes discovering and acquiring art accessible to all.

Learn more