By Aadya Narain

Mahasweta Devi (1990) The hunt. Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 5:1, 61-79.

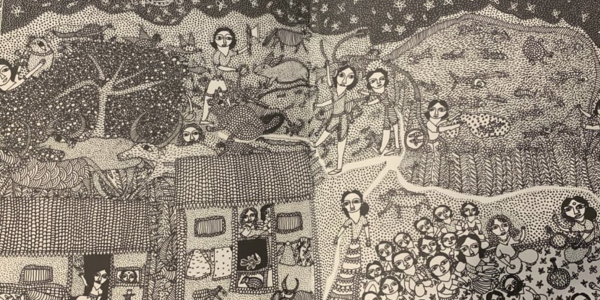

Photo of The Hunt by Mahasweta Devi, taken by the author

Mahasweta Devi is a political activist and author who wrote about subaltern, marginalised communities in India with a piercing feminist gaze. Her deceptively simple and accessible language in “The Hunt” reveals the complex socio-cultural realities of the doubly delegitimised lives of tribal women in India. Tribal communities paid the price of development in a ‘liberal’, postcolonial India, but never reaped the benefits. Women occupy the lowest rungs within these communities, with higher mortality rates, lower nutrition and literacy rates, and increased susceptibility to violence. Published in 1990, this short story traces the life of the fictional Mary Oraon. Forced by her circumstances into a life of autonomy both inaccessible and generally unsustainable for women, Mary navigates survival in a pervasively patriarchal society. Unique to Devi’s narratives is that the prevalent discourse around sexuality in India is reversed; no longer a tool for the oppression of women, it forms the very foundation of their liberation. Through Mary, a dynamic protagonist who exhibits fierce agency, autonomy, independence, and emulates a combination of what are deemed either masculine or feminine qualities, Mahasweta Devi troubles the legitimacy of the rigid gender role imposed upon women.

Mary’s advice about the development of the village and her warnings of the Collector’s exploitative plans are valued by her employer and the villagers alike. She confidently occupies the position of their counsellor and fearsome protector, a role typically reserved for an established male. Her foresight and leadership demonstrates an attachment to community rather than individual benefit. Mary’s commitment to sustainable development reflects numerous contemporary studies evidencing clear linkages between female leadership and pro-environmental outcomes. Moreover, Mary demonstrates astute and far-sighted business sense by working for no wages to earn profit instead, firmly in the androcentric world of earning money and doing business. This is incongruous with the misconception held even in the twenty-first century by managers, and often women themselves, that they lack strategic and financial acumen, despite outperforming men in nearly every relevant skill. Nevertheless, despite reservation and other affirmative policies to empower women in decentralised politics, they remain severely under-represented, or their presence does not translate into power, acting as a façade for men to rule from behind the scenes. Coveted for her indispensable physical labour in Prasadji’s house, ranging from cleaning the house to pasturing cows, Mary dispels notions of the physiological superiority of the male body. Mary’s consistent success in the ‘public’ sphere challenges the notion of the home as the natural and “exclusive site of female labour and affect”, while her independence as an ‘unattached’ woman questions the subjugation of women inherent in traditional familial structures. Simultaneously, transcending her marginalised economic status, Mary unsettles ‘son preference’ prevalent even in modern India, based on the notion that while sons enhance financial resource, daughters ‘drain it through dowries’.

Mary has grown up with the ramifications of ‘illegitimate’ origins and the abandonment of a father who was never held accountable. She has therefore set clear boundaries for any expectations of physical intimacy that her fiancé may have. The arbitrary sanctions imposed upon women rest upon shaky foundations, forcing women to hold themselves to arbitrary standards of morality. Mary is quick to point out the hypocrisy of the heinous proposition by her employer’s brother to “keep her” without any formal relationship. However, she too attempts to adhere resolutely to chastity before marriage, which will be used as a metric to determine her ‘morality’ but must commit a gruesome crime to protect it. Mary’s unflinching demand for consent in sexual encounters exemplifies an integral tenet of the movement for women’s empowerment, which remain unmaterialised in contemporary Indian society where judicial decisions in rape cases value the veracity of a woman’s testimony against her ‘chastity’. Her comfort with wielding her machete reiterates her resolve to preserve her bodily autonomy and tackles the practical consideration of her safety in these male-dominated territories she discomposes. It firmly declares this woman as her own saviour, in stark contrast to the stereotypical ‘damsel in distress’. This tool may also allude to Mary’s determined protest against the dominant patriarchy, owing to its use a symbol and weapon in popular uprisings across the world, particularly against oppressive regimes.

This subversion of dominant gendered norms is fuelled by Mary’s agentive decisions, and a determination to make choices that are wholly her own, as far as possible. A performative aspect of dominant gender norms is the positioning of women as needing to be governed, controlled, protected, or hidden. However, these ‘feminine’ attributes, of sensitivity, kindness, reservation, beauty, grace, generosity, and others, retain a dignified and positive existence outside of their connotation as inferior, personified by Mary’s character. Her behaviour indicates an appreciation of the qualities that constitute both gender roles, and an ability to manoeuvre this fluidity to her advantage. Congenial among peers and admired as the “best dancer”, she could undoubtedly conform to the parts played by women in the only community she has ever known. But “that doesn’t mean she wants to live their life”. She arrives at the marketplace like a “queen” but conducts her business amongst the men as an equal, valued for both friendship and skill. Mary is also coveted by eligible men ready to “fight over her”, and an opportunity for a safe marriage within her place of employment. However, she firmly retains her belief in partnership for happiness, rather than compliance, contends with the ostracization of her traditionally monogamous society for her decision. She has single-handedly saved up the sum agreed upon with her fiancé, but provides him the opportunity to contribute to their marriage evenly, personifying the feminist reimagination of marriage as a less gendered institution of partnership. Devi’s very first description of the character – “seductive” from afar, evincing “rejection” up close– powerfully highlights this dichotomy. Mary’s mixed heritage, partly Oraon tribal, yet possessing the status of a “white man’s daughter”, appears to make her transgression of these boundaries more acceptable. Despite her proclivity for conventionally masculine characteristics of assertiveness and aggression, Mary holds on to her ‘femininity’. She does not fit neatly into either community, nor can she be limited by binary gender roles.

The power of this polarity is evident in Mary’s final triumph over the Collector. Devi sets the scene for this deconstruction and replacement of the dominant through the carnivalesque chaos of the long-awaited ‘hunt’. This year is exceptional, for after over a decade, women are required to prove their mettle at an activity that is often considered the genesis of man as the provider, and thus paramount. Mary foreshadows her ascendancy when she proclaims to her friend Budhni, that after the hunt, she will assume the role of “husband”. This is Mary’s first and only explicit indication of her intention to relinquish the female gender role for the far more liberating male. Mary has arranged a rendezvous with the Collector. She is “laughing” as she seduces him and continues to laugh as she “lifts the machete”, ending his life. The Collector would never have allowed himself to be in a position of such extreme vulnerability with a man, especially one with whom he had recently conflicted. His underestimation of Mary’s potential to take advantage of her position to seek revenge and dignity led to his horrifying death.

Bodily differences between men and women are often used to reinforce gendered biological essentialism. This disparity creates a hierarchy biased against women, who are relegated to a life of subjugation, unexplored and unaddressed by the sheltered female archetype. Intersections of caste, class, race, and sexuality interact to construct various institutions that perpetuate this oppression through socialisation, coercion, and punishment. Mahasweta Devi’s aggressive, enterprising, fearless character has challenged the notion of these attributes as belonging exclusively to the masculine world. Simultaneously, her protagonist possesses those prized ‘feminine’ qualities of consideration, sensuality, nurture, and thus also subverts the notion that the masculine and the feminine must remain mutually exclusive. Mary occupies an unfamiliar and undefined niche eclipsing the binary understanding of gender. That she often cannot confidently inhabit this space she has fought to create, such as when she feels acute fear upon losing grip of her machete (Devi 74) – is yet another failure of a society designed to relegate her to the margins. Devi’s Mary holds steadfastly to all her powerful qualities, not because of her gender, nor despite it, but simply as a response to her circumstances. A challenge is posed to the rigid construction of the female gender role that continues to persevere even today through centuries of entrenched patriarchy. It questions the very idea of stringent gender roles and envisions a more fluid understanding of what truly determines the lives of individuals, their personalities, and the roles they are best suited to occupy.

Aadya Narain is an undergraduate student of law and humanities at the Jindal Global Law School, India.

Aadya Narain is an undergraduate student of law and humanities at the Jindal Global Law School, India.