ArtSeen

Bhupen Khakhar You Can’t Please All

On View

Deutsche Bank KunsthalleNovember 18, 2016 – March 3, 2017

Berlin

Bhupen Khakhar was a true original. An iconoclast. Born in 1934 in Bombay (now Mumbai) to a middle-class family, Khakhar earned a degree in economics at the urging of his widowed mother, working for most of his life as an accountant. Yet, from an early age, he also pursued drawing, painting, and writing with the passion, and arguably the freedom, of an autodidact. A lifelong admirer of Gandhi and champion of the lower classes, Khakhar rebelled against Nehru’s vision of India, against the “good taste” of the middle-classes, and against the modernist style of painting then popular among many of India’s artistic elite. While his style evolved over time, from experimentation with a Pop Art style in the 1960s, to a more eclectic blending of references to artists like Henri Rousseau and 14th-century Sienese painters like Lorenzetti and Simone Martini in the 1970s and 1980s, Khakhar nonetheless maintained his own voice. Khakhar is as famous for his intense use of color—fiery saffrons, saturated teals, and pinks so electric that they almost illuminate the canvas—and unique figurative style, as he is for his exploration of what was once a taboo subject in postcolonial Indian art: male homosexuality.

You Can’t Please All at Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle is the second iteration of an international retrospective of Khakhar’s work, first debuted at Tate Modern in mid-2016. Organized chronologically, the survey showcases the career of the artist dismissed by critic Jonathan Jones, in a controversial review of the exhibit, as a “bad painter” who’d been given a “soft ride” by the Tate because of “some misplaced notion that non-European art needs to be looked at with special critical generosity.” Such dismissiveness reflects a lingering imperialist gaze. Khakhar was not a naïve painter who, lacking the skills or sophistication to work within the framework of Western art history, resorted to a poor imitation of it. His specific motifs, palette, and style were consciously developed and derived from an idiosyncratic dialogue between tradition and modernity, Western art history, and Hindu sacred and popular practices. The result is a highly subjective, deeply personal, and immensely compelling body of work, one that often soars beyond the confines of its particular framework to speak to a condition with which we must all contend, the human one.

Even in his earliest works Khakhar displayed a singular vision, a fresh way of incorporating Western and Indian references and techniques. Interior of a Hindu Temple III (1965) uses bright orange paint synonymous with small Indian shrines to crudely outline the Hindu gods Ram and Hanuman and the goddess Lakshmi. Below the three painted figures appear eight mass-produced posters depicting Vishnu and his avatars. In its pastiche of Indian religious and street culture, the work maintains a somewhat cool, distant perspective, but without irony or disdain for local religious traditions and practices.

Throughout, Khakhar’s oeuvre displays a strong curiosity about the social world of India’s petty bourgeoisie and lower orders. This is embodied most clearly in a series from the early 1970s referred to as the “trade paintings,” in which he portrays different professions in a manner that references both 18th-century colonial painting and Hindu iconography. At the center of Man with a Bouquet of Plastic Flowers (1975) stands a balding, middle-aged man in a collared shirt, arms folded across his chest. His flatly rendered face, with its direct but indifferent gaze, suggests not so much an individual as a type. While such an anthropological impulse might be Western in origin, Khakhar gives it a local inflection by framing the painting with small vignettes, a technique found in 17th-century devotional art. Here they portray not Hindu gods but scenes from Indian daily life: a man napping in a chair, or three men chatting in a small bedroom. Beyond combining two narrative forms, the conceit plays with the tension between society and the individual, and the boundaries between the public and private self.

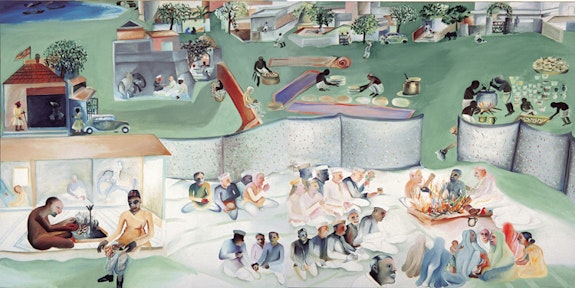

After his mother’s death in 1980, Khakhar no longer felt compelled to keep his homosexuality hidden. His “coming out” piece, and the painting from which the exhibit draws it name, You Can’t Please All (1981), is a subtle embodiment of the desire to both hide from and participate in society. A naked man leans over a balcony and looks out over a village square, observing the scenes playing out below: someone repairing a car, a group of men gathered in a circle, a woman picking fruit from a tree. Amidst the tableau of village life plays out Aesop’s fable about a man and his son who, obeying the advice of well-meaning villagers, end up unintentionally killing their donkey. While the title makes the underlying message clear—follow society’s strictures at your own peril—the central figure’s calm expression conveys ease and curiosity more than fear or judgment.

In his final years, suffering from prostate cancer, Khakhar abandoned the aloofness of his earlier works and painted with a visceral directness. Idiot (2003, the year he died) employs muddy brown paint that seems to have been smeared rather than painted to render a wild-eyed man pissing into his shoe. Staring straight at the viewer, he tears at his cheeks with both hands, as if trying to split his face in two. His feral gaze is not merely that of a crazy man; it’s desperate, haunted by a fear and a pain so overwhelming that he seems completely indifferent to the presence of the man behind him, who points and laughs. The violence and pain of social isolation and the agony of illness and anticipated death are so vividly rendered, so raw, that it is as if Khakhar himself had merged with the canvas. It is an image you will not soon shake.