ArtSeen

Robert Frank: After The Americans

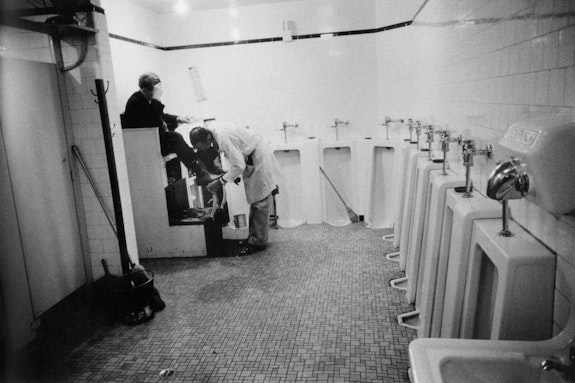

With Robert Frank’s death last September at the age of 94, critics, photographers, and publications—not least the Rail —eulogized him at length as a revolutionary photographer, who transformed documentary photography by breaking the rules, getting personal, and challenging the self-regard of the world’s most dominant superpower as it emerged in the 1950s. The New York Times gave Frank the kind of space usually devoted to major heads of state and a-list celebrities (more than it devoted to Ingmar Bergman, for example, or Michelangelo Antonioni). Writer Philip Gefter titled a collection of essays Photography After Frank (2009), as if this single figure marked a turning point for the medium as a whole. Most of the praise focused on a single achievement, his book The Americans (first edition in French, 1958). It has gone through multiple editions and in 2009 received the ultimate hagiographical treatment from the National Gallery. The exhibition Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans analyzed every aspect of the publication, from the genesis of the pictures, with the holy relics of work prints and contact sheets, to the book’s reception, to Frank’s highly particular editing and sequencing. After The Americans, Frank largely left documentary photography behind in favor of films and other photographic projects. Since the reputation and regard rest largely on this single project, then, it is worth “looking in” at The Americans again to see if the claims for it are justified—or relevant.

What most people who know The Americans know about it is that it ruffled feathers. Certainly Frank’s vision of America was anything but shiny and new. It was, rather, tattered and worn, not to mention a bit dour—“a wart-covered picture of America,” one critic called it at the time. And the American edition carried the hipster credential of a preface by Jack Kerouac, Beat author of On the Road (1957). That imprimatur reinforced, and still does, the idea that the project was aligned against middle class proprieties. It portrayed a raggedly diverse America of subcultures—Black evangelicals, motorcyclists, and urban cowboys, to name a few. Which is why Frank came here in the first place—America was the anti-Switzerland, no place like home. Yet even in the context of mounting Cold War anxiety and nationalist sentiment, Frank was far from the only photographer to deliver a bitter, skeptical pill about this side of the Iron Curtain.

Take the matter of race. One of Frank’s most famous and controversial images shows a segregated trolley in New Orleans. By the time Frank set out on the cross-country trip that would lead to The Americans, race was already established as a central issue in American life, and discrimination was a frequent topic in the northern and national press. Many indelible images were already in circulation, including the most moving photograph of all, David Jackson’s 1955 picture of Emmett Till’s body in the morgue, with a dazed and saddened Mamie Till, his mother, looking on. Gordon Parks, Dan Wiener, Ernest Withers and Helen Levitt, to name only a few, had long since begun to chronicle the urban realities of being Black in America. Frank’s photograph would have seemed rather tame by comparison. It’s a subtle photograph, showing nothing more than passengers, some Black, some White, looking out of the windows of the trolley. To anyone unaware of racial politics in the deep south, the photograph could not be understood without explanation, not to mention the visual context provided by the work of these other photographers.

The realities of race would culminate in the mid 1960s in the searing reportage of the Civil Rights movement, a movement in which Frank played no role. By the same token, in terms of a broader critique of American society, Frank was hardly alone. Indeed, the mean streets were crowded. From Lewis Hine to Louis Faurer, American photographers, many of them immigrants, had already made careers out of revealing that the Garden of Eden was overgrown with thorns, even in the pages of such patriotic drum beaters as Life magazine. And popular culture was rife with evidence of inner anxiety, expressed by Marlon Brando’s star turn as a swaggering outlaw cyclist in The Wild One (1953) and of course by Rebel Without a Cause (1955). These films presage some of Frank’s images, especially leather-wearing motorcyclists festooned with their club symbols in Newburgh, New York and Indianapolis. Trouble had already come to River City.

Unlike Guggenheim Fellow Frank, stamped with the approval of Walker Evans, many photographers operated mostly as photojournalists, and they were under the commercial aegis of editors and curators like Edward Steichen, who masterminded The Family of Man exhibition in 1955. Their work could be edited into an upbeat humanism, whether or not they shared such a view. It is worth asking how much the audience for a book like The Americans would have dovetailed with the broader public that may have seen photography’s role as other than personally expressive.

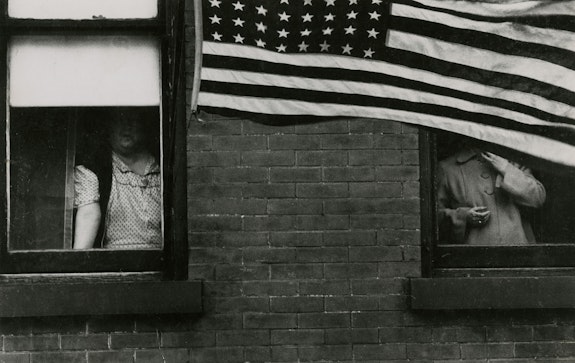

But Frank made one distinctive gesture that would continue to bring him and The Americans, even six decades later, the kind of notoriety most photojournalists didn’t get: he wrapped his cultural criticism in the American flag.

In case anyone missed the point, The Americans opens with a wonderfully dense and disquieting photograph of two people watching a parade from open windows in Hoboken, New Jersey. One is partially cut off from view by a huge American flag draped across the building’s façade. So much for unthinking patriotism. Frank reprises flag imagery at key points throughout the book as critique and visual punctuation. The flag comes in for some pretty ironic treatment in the book, including as an outdoor sun shade in a wildly overgrown backyard in Venice, California. Such images appeared to many critics as if someone from outside, from “old Europe” (Weren’t we still paying their way to post-war recovery and keeping the Soviet bear from the door?) were presuming to tell “us” about our issues. Downright ungrateful. And because the first edition was published in France, the book arrived already with a whiff of foreign effeteness.

But Frank’s reputation depends less on giving offense than giving permission. Like a jazz musician, he is credited with pioneering a new style of documentary photography based on improvisation and rhythm rather than rules of intelligibility. His cool attitude, his ability to shift between formalism and a flirtation with chaos is also reputed to have had a decisive influence on subsequent generations, including Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand. This description, however, is overstated on two counts. First, it downplays many other radical departures in photography of the time. Frank was hardly the only one breaking the rules—if indeed there was a rule book. To take only the most glaring examples, William Klein’s New York 1954.55 provided an immersive visual experience, with all photographs printed full bleed and most shot at an altitude between the knees and the chest, the strike zone of a hitter who always swung for the fences. It’s impossible that Frank wouldn’t have responded to the immediacy of Klein’s stream of consciousness approach. Even earlier, Lisette Model imported into the United States a street style that could be raw, grotesque, often formally challenging, and socially extreme. Mentor to Diane Arbus, Model could justly claim to be underappreciated. Her own credo might have been spoken by Frank: “The picture isn’t straight. It isn’t done well. It isn’t composed. It isn’t thought out. And out of this imbalance, and out of this not knowing, and out of this real innocence toward the medium comes an enormous vitality and expression of life.” For younger women in photography, it is Arbus (and thus indirectly Model), not Winogrand or Friedlander, who, in spite of the moral complications of her work, continues to give permission.

Claims of Frank’s influence likewise need qualifying. Garry Winogrand was already working professionally in the 1950s, and by the time The Americans appeared, he had shot several of his most striking, even iconic, photographs. His signature approach of tactical engagement and undaunted invasiveness, as he waded into a crowd like a man pushing through a turnstile, was fully operational. If Frank saw the social fabric in terms of categories and symbols, including class, race, religion, and occupation—a habit straight out of historicizing old Europe—Winogrand had no interest in specifying those connections. Just the opposite. It is not clear that he thought there was such a thing as society in America, only incomprehensible monads. And where Frank’s contact sheets are among the most concise and productive ever seen, Winogrand simply stopped making them. His legacy was the opposite of The Americans, with its careful sequencing: an inchoate archive of unexamined, half-articulate images.

The Friedlander question is more complicated, and it illustrates the limits of Frank’s approach and perhaps of his relevance now. Like Winogrand, Friedlander was already at work professionally before The Americans, making important photographs on the jazz scene. No question both Frank and Friedlander as photographers saw America as a visually mediated world. Signs are everywhere in their work, along with brand names and logos, features of the American photographic landscape at least since the 1920s. Frank early on recognized television as a binding force in America, for better or for worse, and in 1963, Friedlander published a handful of television photographs titled The Little Screens. But the latter went much further, expanding the notion of mediation to windows, mirrors, even shadows of the photographer himself, and by extension to the medium of photography. It becomes almost a given in Friedlander’s work that the world cannot be encountered directly. This phantasmagoric sense of infinite regress, in which the camera itself plays a central role, diverges fundamentally from both Winogrand’s magical thinking about photography (He never missed a picture because, as he famously remarked, if he didn’t capture it, it didn’t happen) and Frank’s expressive flexibility.

We recognize Friedlander’s preoccupations as themes of Pop art, and in his work’s repetitiveness and attention to language, we see an affinity with conceptual art. For if Frank and his supposed epigones inaugurated a subjective, personal documentary style, concerned “not to reform life but to know it,” as MoMA curator John Szarkowski insisted in his 1967 exhibition New Documents, it was others, often arriving from outside the world of photography, true foreigners, who were thinking more critically about the photograph as document, its use, production, consumption, and distribution. Looking back, Ed Ruscha’s self-published Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations (1963) seems almost a direct response to Frank’s vision of America—unexpressive, unpopulated, and generic. There’s a gas station in The Americans, but its semi-abandoned decrepitude and portentous sign reading “SAVE” seem to symbolize a departed spiritual and economic authority. Ruscha’s gas stations, on the other hand, are about an America taking shape, with the camera as handmaid. The structure of Ruscha’s small book contradicted exactly Frank’s narrative control, substituting a one-thing-after-another seriality.

Only a few years later, conceptual artist Mel Bochner would begin to make explicit the sea change in photography’s place in the art world when he initiated a deconstruction of the medium that yielded Misunderstandings (A Theory of Photography), 10 index cards with quotations revealing aspects of the medium often taken for granted. It opened with a quotation from the Encyclopedia Britannica: “Photography cannot record abstract ideas.” Of course not, since only what light touches can film record. But from the early 1960s on, more and more photographs in an art context were motivated by ideas and not by so-called photographic vision, not by the kind of distinctive, even idiosyncratic attitude Frank’s pictures embodied.

The anti-narrative, typological character of photography would be exploited by artists around the world, most notably by Bernd and Hilla Becher in the archive of obsolete industrial architecture they began shooting in 1957. Many others would use suites of similarly uninflected images to explore issues of series, sequence, and performance. It is difficult to reconcile Frank’s restless expressiveness, and all that it represents of the Beat generation avant-garde, with Giovanni Anselmo’s Interference with Universal Gravity (1969)—20 nearly identical photographs of the setting sun he took while walking in a westerly direction—or for that matter with Hannah Wilke’s Gestures (1974), a suite of 30 closeups of the artist manipulating her own face. The photographs break no rules and look like they could have been taken by anyone.

By now, any photographers following this argument will throw up their hands in familiar frustration and exclaim, “But this is the old story of artists using photography, not photography done by photographers.” However, it’s not just that the house of photography has many rooms but that behind even the most deadpan and modest conceptual use of photography lies the recognition that there is no natural photography, and that all uses of the medium are nested in conventions of presentation and reception. These are, at bottom, linguistic functions. They are coded transactions that operate not solely at the behest of the photographer, no matter how apparently “original” or “revolutionary.” Regardless of what the camera is looking at, regardless of the content of the pictures, the implicit subject is photography itself: how it portrays, how its meanings are constituted, who’s looking at it, and for what reason.

To convey his insights, Frank had to take most of these issues for granted. The self-consciousness of the medium ran directly counter to his intentions. Contemporary photography bathes in it. When Myoung Ho Lee places a sheet behind a tree as a backdrop or when the London-based duo of Broomberg and Chanarin display a seventeen-foot abstraction as an example of conflict photojournalism or even when Nan Goldin, the ostensible visual diarist, chooses to stage her most intimate and revealing glimpses, they may alter our sense of the way things are but much more so of the way things are represented. As for the internet, that platform of supposedly naïve photographic self-regard, when Argentinian Amalia Ulman ended her months-long masquerade on Instagram, Excellences and Perfections (2014), she did it with the thoroughly fictional conclusion, “The end.”

In The Americans, Robert Frank may have appeared as a revolutionary photographer, but beyond The Americans, the real revolution in photography was taking place elsewhere.