- India

- International

Film of the Month: Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi tells us everything that is wrong with the Left

Author Kiran Nagarkar praised Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi as "one of the finest political films." The 2005 political drama exposes the hypocrisy of the Left movement by revealing the huge gap between its naïve romanticism/intellectual activism and its utter failure to make a better and more just world.

We begin our ‘Film of the Month’ series with Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi.

We begin our ‘Film of the Month’ series with Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi.

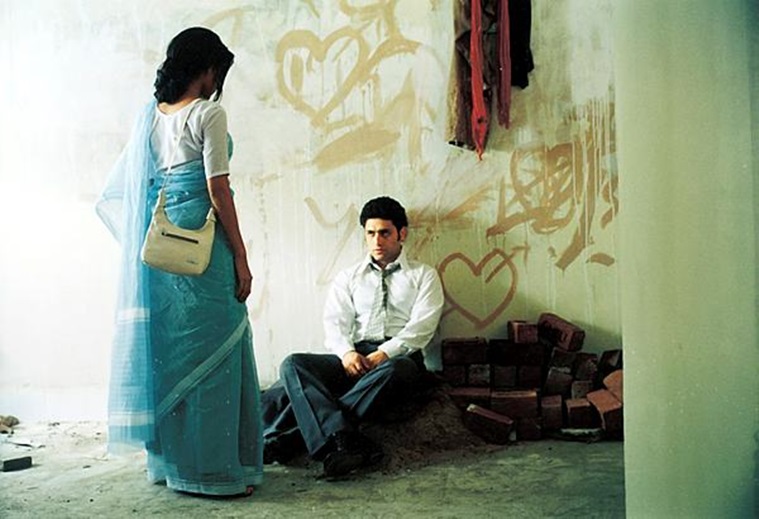

Film: Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2005)

Director: Sudhir Mishra

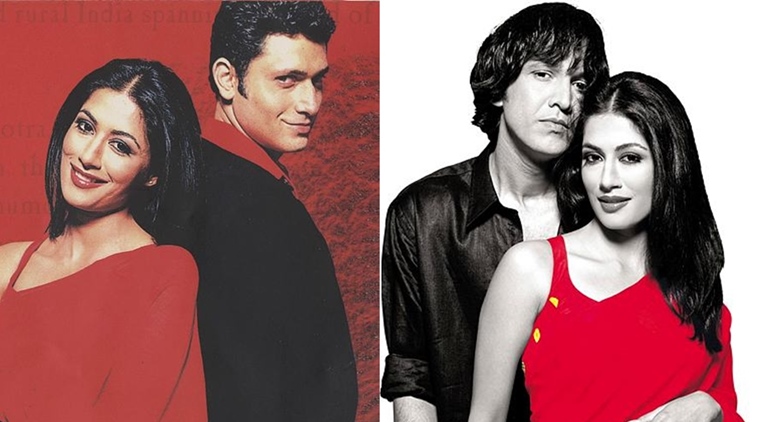

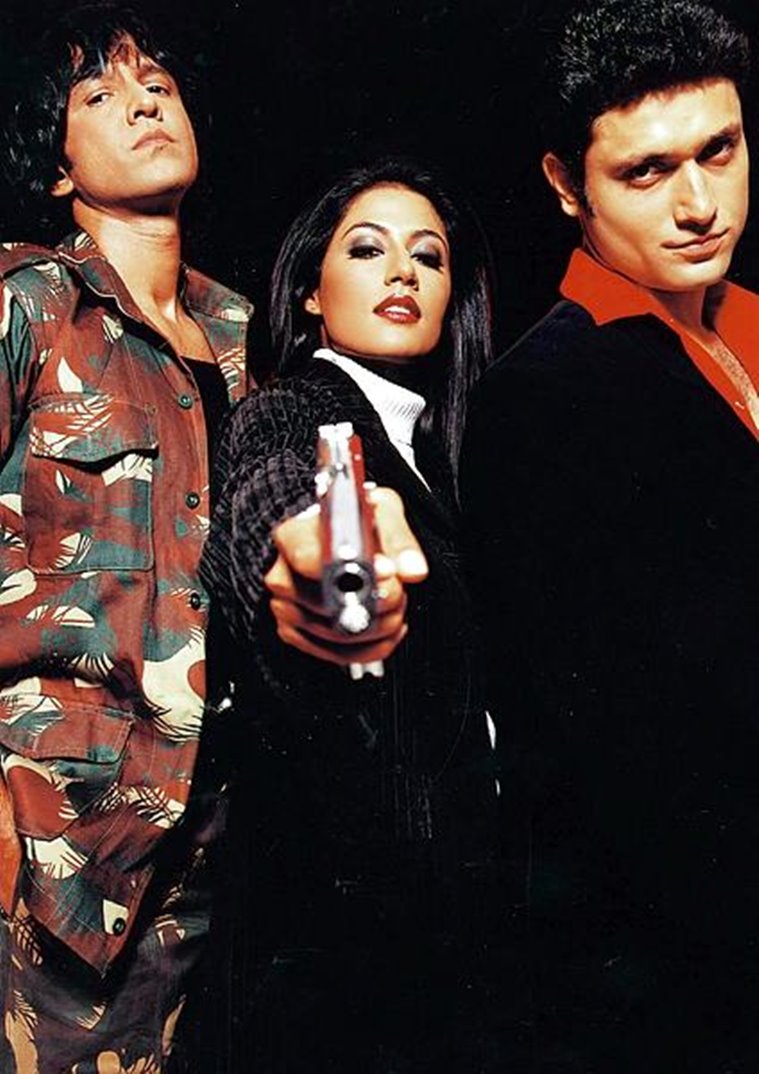

Cast: Kay Kay Menon, Chitrangada Singh and Shiney Ahuja

“Pandit Nehru made a horological mistake.” Thus, begins Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, declaring (though not decrying) the so-called Nehruvian dream as a nightmare. “At the stroke of midnight when India awoke to ‘light and freedom’, the world was not asleep. It was for instance, around two thirty in the afternoon in New York,” the film notes, with irony. Released in 2005, the relatively low-budget, no-star Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi quotes from Nehru’s iconic ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech on the eve of 1947, but the film is really about love and conflict in the time of Indira Gandhi. The daughter of India’s first Prime Minister and the infamous 1970s Emergency imposed by her in the most fascist fashion disrupting democratic ideals forms a heady backdrop for Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi.

With its depiction, and subsequent disillusionment with Nehruvian socialism, Mishra’s political drama recalls a time when revolution was in the air. In essence, Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi is JNU student politics come to life. The high-caste, privileged characters that populate Delhi of the film’s imagination are highfalutin forerunners of – to borrow from the vast and highly innovative vocabulary of the right-wingers – ‘Urban Naxals,’ ‘Twitter libtards,’ ‘Tukde tukde’ gang and ‘anti-nationals.’ Characters in Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi talk about ideals, oppression, poverty, capitalism and inequality with passion but their bourgeois-by-birth background is not lost on the audience. As an astute filmmaker and close political observer, Mishra is interested in this dichotomy and as he goes about charting the course of the three young lives at the centre of his tale, he throws some of his own wit and cynicism into the mix. But in the end, the film is Mishra’s ode to poetry and politics and only this most ardent of Ghalib fanboys could have thought of blending those two distinct forces to craft what is clearly one of Bollywood’s most potent and thought-provoking political dramas.

Children of Marx and Hendrix

The year is 1969. The film kicks off with Siddharth Tyebji (Kay Kay Menon) and his band of opinionated comrades in the thick of revolution. He’s written yet another impassioned letter to college sweetheart Geeta Rao (Chitrangada Singh), in which he expresses a desire to change the world. What about changing yourself? That question is best left to viewer discretion. Brimming with fiery idealism not uncommon in the Marx-reading rich, the radical Siddharth (son of a mixed marriage) has renounced a cushy life to follow what he calls the muddy road to “end the vulgarity of oppression.” In the letter to Geeta, his ideology becomes evident. “The violence of the oppressed is right,” he says. “The violence of the oppressor is wrong. And to hell with ethics.”

Characters in Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi talk about ideals, oppression, poverty, capitalism and inequality with passion but their bourgeois-by-birth background is not lost on the audience.

Characters in Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi talk about ideals, oppression, poverty, capitalism and inequality with passion but their bourgeois-by-birth background is not lost on the audience.

These ideas and thoughts animate pretty much the entire film. The interplay of politics and social change, the role of the individual and that of the state and freedom and exploitation are constant reminders that the world we live in is far from fair and equal but how to make it a better place and whose responsibility is it? Even if it doesn’t work, as Siddharth seems to foolishly believe, “it’s worth the effort.” To counterbalance Siddharth, Mishra drops in the glib Vikram Malhotra (Shiney Ahuja). Ambitious and go-getter, Vikram is the scourge of Siddharth. Like him, he is born to an influential and overbearing father but does not hide his contempt for revolution. A quintessential political climber, he is the neglected son who wants to get rich and famous and probably, break off from his father’s shadow as promptly as the Delhi power corridors can permit. When we first meet Vikram, he’s plotting his way out. “I can’t understand you rich kids playing this ‘let’s change the world’ game. While you are looking for a way out, I am looking for a way in,” goes Vikram’s mantra. Sure enough, some years later, he is described as an “upcoming tycoon.”

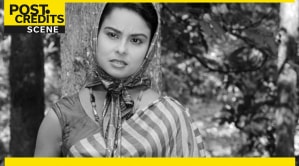

And then, there’s Geeta, played with flourish and sublime beauty by Chitrangada Singh. Shortly after the movie released, critics felt the need to compare her smoky sex appeal to that of the late Smita Patil’s. Indeed, if this were a Shyam Benegal film, bet Patil would have played the victim of male or social exploitation – or both. (Minor detour: It’s foolish but it feels tempting to imagine what if Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi was made in the 70s with Patil, Om Puri and Naseeruddin Shah as its stars and what kind of a film that would have been?) But this being a Sudhir Mishra film, it’s nothing short of literally being worshipful of the woman, especially as Geeta finds herself as the much sought-after romantic interest of the two men. She loves the intense Siddharth, but a jealous Vikram is on her tail, too. Mishra establishes this love triangle early on as Siddharth and Vikram send out letters to Geeta, the one from Vikram unequivocally announcing, “Dear Geeta, first things first, I still love you.” A typical New Woman, Geeta is not afraid to take the sexual initiative and is casual about her sexuality even after marriage (Ram Kapoor; she ultimately ends the marriage). She sleeps with old flame Siddharth behind her husband’s back. If there is any guilt or remorse, it quickly vaporises in Siddharth’s noble arms. After all, the passion that Siddharth ignites in her is not something she can expect from her alcoholic bureaucrat husband.

A lament or love letter to Utopia?

Vikram, Siddharth and Geeta are the archetypical product of the Seventies, or as the Seventies that existed in Sudhir Mishra’s silver-haired memory. The children of Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix dance and drink the nights away even as they try so hard to use the ‘laal salaams’ to justify their lifestyle. Is ‘revolution’ merely an empty talk? A budding politician who visits Vikram in his hostel is alarmed to find pin-ups of Marilyn Monroe, The Beatles and Bob Dylan when it should have been Gandhi, Nehru and Bose. Who do these young folks look up to? Led by Siddharth, the smoke and booze-fuelled discussions on the campus border on ideological wars. One says the Gandhian idea of revolution in the villages predates Mao’s even as someone else counters, trenchantly, “All that Mr MK Gandhi did was to become the guest of rich Marwari businessman.” And with that, the chillum, like the baton, is passed down from one so-called armchair intellectual to another. Amidst this heated round table of politics, Mishra sneaks in a tender scene – Sahir Ludhianvi’s Marxist anthem “Woh subah kabhi toh aayegi” renting the air – between Siddharth and Geeta in which she asks him if he truly loves her. (For those who appreciate finer nuances and devil-is-in-the-detail, note the splendid transition which occurs when a dazed Geeta is spinning to The Seekers’ “Georgy Girl” at a get-together and all of a sudden, the music shifts to the qawwali “Bawra Mann”.)

Mishra’s poetic touch and love for music is at par with his anger and bitter humour, all of which are beautifully embedded into the script. For instance, when Siddharth talks about establishing a new social order and says that life is not all about getting a “proper English education, fat salary and loving one’s parents” it sounds funny, because he’s speaking in English himself and he’s a beneficiary of the same convent education he’s pet-peeving about. The joke in “loving one’s parents” bit isn’t exactly hidden either. Is it the offbeat Mishra’s pent-up outrage against Bollywood’s KJoism and its escapist romps? Well, to Mishra’s credit, he has operated on Bollywood’s margins for decades with nary a complaint. So, let him have the last laugh. Funnier still is a scene in which a rich landlord down with a heart attack agrees to be treated by a lower-caste doctor while his son objects. More hilarities: an heir apparent who still answers to the higher calling of socialism but cannot throw away the trappings of the good life. When Vikram jokes that the state of affairs worries only his father and a total of 30 of his Gandhian comrades and some ne’er-do-well socialists (“Worrying is my father’s main profession”) or when he’s seen urinating under the open sky, reciting, “If there’s bliss, it is this.”

Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi is a love story, equal parts a lament and love letter to a generation that Sudhir Mishra vociferously believes “failed me.”

Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi is a love story, equal parts a lament and love letter to a generation that Sudhir Mishra vociferously believes “failed me.”

Yet, the film, though subversive, irreverent and audacious, is not aiming for laughs. As the years pile on, Mishra pursues the life story of Siddharth, Vikram and Geeta in a loose coming-of-age but he’s eager to impart his characters a pay-off. The commitment to his cause forces Siddharth into years of instability out in the boondocks. Vikram, as rightly predicted, becomes Mr Fix-It in Delhi’s power echelons, ostensibly under the auspices of a figure resembling Sanjay Gandhi. The film’s central conflict comes from Siddharth and Vikram’s philosophical clash. Where does Geeta stand here? As Vikram repeatedly reminds us, she’s the eternal “lost soul.” The film, in that sense, is a love story, equal parts a lament and love letter to a generation that Mishra vociferously believes “failed me.” It received a seal of approval from none other than author Kiran Nagarkar who applauded Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi as “one of the finest political films.” Appearing as a talking-head in the documentary Bawra Mann, Nagarkar added, “I felt challenged by this movie.” Mishra has himself identified it as his most intensely personal work and it is not surprising to discover a dedication to his late wife Renu Saluja in the ending credits. He even appears in it, twice. Once, cracking a joke about snoring and sometime later, as the voice on the phone mouthing tongue-in-cheek one-liners. Revisiting the film in 2011, Mishra told CNBC-TV 18 that, as a filmmaker, he had always wanted a connection with the audience, “but on my own terms.” In Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, more than any other film, he managed to achieve that. The movie straddles all the big issues of the 1970s but never without a touch of poetry and dewy-eyed romance. It is Sudhir Mishra’s angriest (sorry, Saeed Mirza) and yet, his most optimistic film to date.

Most importantly, Mishra deserves credit for seeking to expose the hypocrisy and double standards of the Left and its intellectual activism by revealing a huge gap between the naïve romanticism of the socialist theories and what it can truly achieve on the ground. The Leftists are totally disconnected, the film appears to argue, from the unpleasant realities as they pontificate in their ivory towers, far removed from where all the action is. This disconnect is best interpreted in a throwaway scene at a rally in which a farmer asks, “Who’s Hitler?” and a fellow seated next to him shakes his head, “He’s definitely not from our village.”

The film’s fundamental question, ‘Can socialism ever be a force for public good?’ draws a blank in the end. At best, crusader Siddharth is still trying to find an answer to it before his plunge into the Naxalite movement. Shiney Ahuja’s Vikram was never fully on board while Geeta Rao, the film’s most mysterious figure, is the naif who is lured into it from time to time by her ex-lover. She submits eventually. Sudhir Mishra, however, has the final word. “I think it is about the vestiges of beauty that lasts when youth fades,” the director told Hindustan Times in 2018. That’s why, he said, the title is an inspired moniker alluding to Ghalib’s philosophical abstractions. Nobody knows the answer, neither Marx did nor Ghalib. Certainly not Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi’s well-meaning radicals and their convenient idealism.

Click for more updates and latest Bollywood news along with Entertainment updates. Also get latest news and top headlines from India and around the world at The Indian Express.

Photos

May 02: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05