- India

- International

Drawing from the Margins: Bhupen Khakhar’s art practice was informed by a vibrant radicalism

One of the first Indian artists to come out of the closet and talk about alternative sexualities, Bhupen Khakhar’s art practice was informed by a vibrant radicalism. Fifteen years after his death, as the Indian market begins to appreciate his genius, a look at the enduring legacy of his art and why he continues to be relevant today.

Bhupen Khakhar’s works exist as comments on the functioning of human relationships with each other and with society. (Illustration: Shyam)

Bhupen Khakhar’s works exist as comments on the functioning of human relationships with each other and with society. (Illustration: Shyam)

When Tate Modern, London, held a retrospective of the late Bhupen Khakhar’s work in 2016, it titled it “Bhupen Khakhar: You Can’t Please All”, after a 1981 oil painting by the artist. The painting it referenced featured a naked male figure leaning across a balcony, watching an ancient fable play out below. A father and son were on their way to a market with a donkey. On the long trek, they took turns at riding the beast. At each turn, passers-by had an opinion to offer on who should be riding the donkey. In the end, the father tells his bewildered son: “Please all, and you will please none!” Painted a year after his mother’s death in 1980, the work is cited by British artist Timothy Hyman as Khakhar’s “coming-out painting”.

Probably the first Indian artist to come out of the closet, the personal aspirations and anxieties of Khakhar’s homoerotic self became a subject of his works in later years and resulted in some of the most arresting gay iconography across the world. In an India that criminalises “unnatural” sexual intercourse, which includes homosexuality, under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, Khakhar — often considered India’s first pop artist — was a radical who dared to question convention and challenge what was considered acceptable. “He was an extraordinary visionary and an inspiration. Even today, it is hard to paint on homosexual themes in India and he was doing that decades ago, even before the debate over Section 377 had started,” says artist Balbir Krishan, 44. Like Khakhar, Krishan is homosexual, but the painter from western Uttar Pradesh had to face the wrath of the moral police at his 2012 exhibition dedicated to Khakhar in Delhi’s Lalit Kala Akademi. The show was vandalised because of some works that showed homosexual themes and Krishan, assaulted. “It’s depressing not to be allowed to paint what you want. Khakhar was not scared of regressive elements and his work was never guided by what the market wanted. I wonder, though, if he could have painted what he did now considering the kind of censorship that one is threatened with,” says Krishan, who has since relocated to Albany, USA.

New idioms: An illustration of Bhupen Khakhar based on a photograph by Jyoti Bhatt/Asia Art Archive. (Courtesy: Swaraj Art Archive)

New idioms: An illustration of Bhupen Khakhar based on a photograph by Jyoti Bhatt/Asia Art Archive. (Courtesy: Swaraj Art Archive)

Fifteen years after his death, at a time when India is going through a period of great political and social churn, what makes the art of Khakhar relevant and explains the escalating worth of his work? At the Christie’s London auction “South Asian Modern + Contemporary Art”, on June 12, the lots included three of Khakhar’s works among other highlights, all of which sold above the estimate. Among them was a set of three 1995 works on paper. Estimated to fetch between £4,000-6,000, the lot came under the hammer for £10,000. Last October, his 1972 oil De-Luxe Tailors from his Tradesmen series, whose pre-sale estimate was Rs 2-3 crore, sold for Rs 9.5 crore at a Sotheby’s auction, a record for the artist. “His art is not about depicting everyday life frivolously; rather, it is injected with close observations and humour. His works exist as comments on the functioning of human relationships with each other and with society. His interest in the ordinary, his affinity towards the weaker and the broken, his nature of embracing the ones on the peripheries, all extended to his artistic language,” says Rajeev Lochan, artist and former director of the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Delhi, who had organised an exhibition of his work at the NGMA in 2016. Lochan has also curated the ongoing exhibition “Liberation/ Revelation/ Representation” at the Swaraj Art Archive in Noida that has 149 works by the artist on show.

The youngest of four siblings, Khakhar was born in Mumbai into a middle-class Gujarati family in 1934. Khakhar’s father, who was a woodwork instructor in an engineering college, died when the artist was just four. At his mother Mahalaxmi’s insistence, Khakhar trained to be a chartered accountant and worked for years, first in Mumbai and then in Vadodara. It provided him a steady income at a time when artists had little financial security. Even though he had expressed his interest in a career in art, the announcement that he was moving to Baroda to pursue a Master’s in art criticism from MS University of Baroda did not go down well. “Nobody in the family was talking to me. CA, bungalow, car, flourishing practice, a queue of girls waiting to be matched… all their dreams were shattered,” he said in an interview in The Wordsmiths (1996, Katha), edited by Meenakshi Sharma.

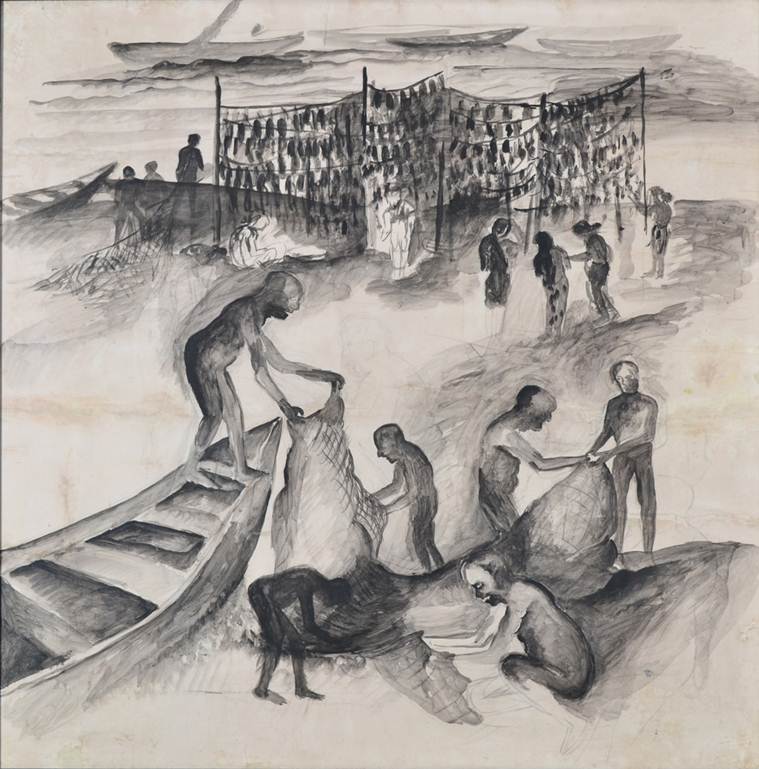

Khakhar’s works on display at the Swaraj Art Archive in Noida; Fishermen, 1989. (Courtesy: Swaraj Art Archive)

Khakhar’s works on display at the Swaraj Art Archive in Noida; Fishermen, 1989. (Courtesy: Swaraj Art Archive)

Artist Gulammohammed Sheikh remembers his first meeting with Khakhar. It was around 1959-60, when Sheikh was pursuing his post-graduation at the MS University. Khakhar was a young chartered accountant working with AF Ferguson in Mumbai who used to attend evening classes at the Sir JJ School of Art in the city. “I think one reason Bhupen brought me close to his mother was that he hoped that I would help persuade her to let him give up his job and move to Baroda,” recalls Sheikh. And he did. With his help, Khakhar quit his well-paying job in Mumbai and relocated to Vadodara, a city where he found the freedom and the anonymity he needed to pursue his art. “I wanted complete freedom,” he wrote in an exhibition catalogue. “At the back of my mind, it also must be my gay attitude.”

The city of Baroda gave Khakhar what he wanted — absolute independence. His home, Parmanand, named after his father, was a venue for informal gatherings, where both friends and strangers were equally welcome. People arrived at all hours, staying back for as long as they wanted. Sheikh, in his essay on Khakhar, ‘Bheru’ (Buddy), writes, “He was a party animal: paint and work all day, enjoy the evening, party every night.”

His education in art criticism familiarised Khakhar with the works of the Western masters. He was in the midst of artists who were at the forefront of developing a modern art aesthetic in newly-independent India, and his art was an expression of a wide amalgam of interests. A collector of film memorabilia and popular art, his early references ranged from Kalighat paintings to miniatures, calender art and even firecracker wrappings. In 1965, when his first exhibition opened at Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay, some critics panned the show, but it was well-received by the artist community at large. “Bhupen was transgressive in different ways at different times. In the 1970s and early 1980s, he focussed on the local, the immediate, and the intimate. He opened up a variety of experiences that had previously not been the focus of Indian art, like the neighbourhood rendered in its specificity, and middle-class domestic interiors. His way of rendering figures, as curiously limp yet animated, and his choice of garish, sometimes shocking, colour, was revolutionary. His second revolutionary moment came in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when he came out as India’s first gay artist, expanding the gamut of Indian art to include experiences that had not previously been voiced, and which were at risk from social sanction as well as the law. The third revolution in his career was not well-recognised — this was his rehabilitation of the sacred in the secularised ethos of contemporary art, especially in his Sri Lanka notebooks and accordion works,” says art critic, cultural theorist and curator Ranjit Hoskote.

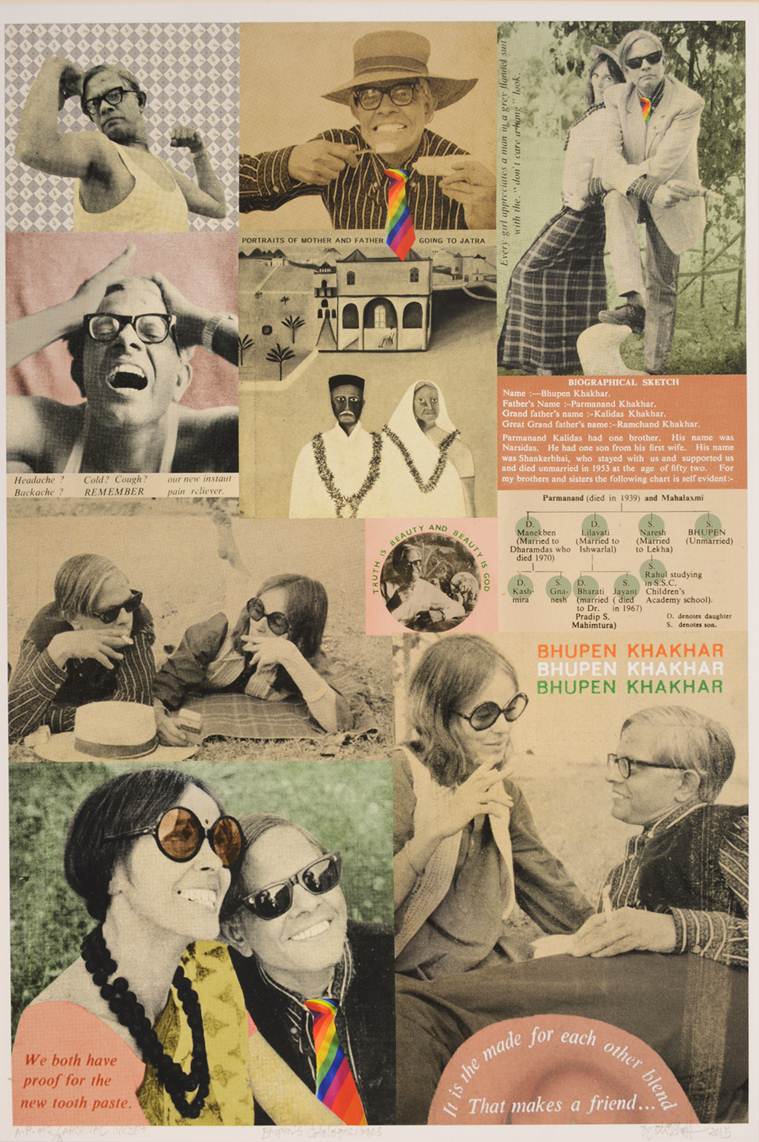

Window to the world: Pages from Khakhar’s catalogues by Jyoti Bhatt. Courtesy: Swaraj Art Archive

Window to the world: Pages from Khakhar’s catalogues by Jyoti Bhatt. Courtesy: Swaraj Art Archive

Among Khakhar’s admirers was Khorshed Gandhy from Chemould Prescott Road gallery who was among the first to exhibit his works. Even though the market did not give him his due, Khakhar’s art was noticed and discussed. “In retrospect, we would do better to see him as laying the ground for a counter class-culture, one rebuking the very class of viewers to whom high art is addressed and to whom, at any rate, it is accessible and available,” writes Geeta Kapur in Khakhar’s retrospective exhibition catalogue for Museo Nacional, Centro de Arte, Reina Sofia, Madrid, 2002.

In the 1970s, when the Baroda School came to be recognised for its focus on figurative art and narration, moving away from the modernism associated with the Bombay Progressive Artists Group, Khakhar was a diarist painting faux naif pictures of barbers, tailors and watch repairers, often playing with imagery and presenting a larger-than-life perspective. Underneath the whimsy and the flamboyance, his artwork spoke of the anxieties of the common man, from a tailor in The De-Luxe Tailors (1972), to a watch repairer in Janata Watch Repairing (1972). One of his seminal works and what has become an iconic painting in the history of modern Indian art, Man with a Bouquet of Plastic Flowers (1976), shows a melancholic figure set against the faux vibrance of calendar art, indicating a life of loneliness and monotony. “Bhupen was among the few artists of the time recreating his observations of the urban middle-class Indian man with acute attention to detail. It was not universal, transformed, stylised figuration, but very specific. For him, art was not something on a high pedestal. He did not want to do decorative paintings, it was about life,” says artist Atul Dodiya, a close associate of Khakhar, who had even assisted him in painting the sets of the Gujarati play Mojila Manilal in 1989. “Despite being self-taught, he had a strong confidence that he was a good artist. That comes through in his work as well as his private and public engagements,” says artist and friend Vivan Sundaram.

In 1979, after his visit to London, Khakhar found the confidence to vocalise his sexuality openly. “I was very much ashamed of my sexuality… Up to 1975 I felt that if my friends knew I am gay, I was prepared to commit suicide… After my visit to England in 1979, I saw that homosexuality was accepted,” Khakhar told Hyman in the 1998 publication, Bhupen Khakhar. In London, on the invitation of the Bath Academy of Art, Khakhar produced some of his most celebrated works, including Howard Hodgkin’s House on Hand Painted Cushion, that was part of the Sothebys October 2017 auction as well as Khakhar’s first foreign solo exhibition at the Anthony Stokes and Hester van Royen Gallerie in 1979. He subsequently returned to the UK to exhibit at Knoedler Galleries (1983) and Kapil Jariwala galleries (1995).

American Survey Officer (1969). (Courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art)

American Survey Officer (1969). (Courtesy: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art)

“At the beginning of his career, the main interest in his work was in Europe and America. He was very well-known and respected in the art community, but it probably took longer for him to gain acceptance in India because of the subjects and treatment of his works. Because he had a reputation of producing more erotic pieces, people were nervous about it,” says Brian Weinstein, American political scientist and retired professor from Howard University, who shared an enduring friendship with Khakhar. Owner of over 100 works by Khakhar, Weinstein also manages a website dedicated to Khakhar, bhupenkhakharcollection.com.

Vijay Kumar Aggarwal, founder of Swaraj Art Archive and owner of one of the largest private collections of Khakhar’s art, says in a country reluctant to talk about sexuality publicly, art depicting homoeroticism is hard to sell. Though he began collecting Khakhar two decades ago, even his collection of 125 works does not feature Khakhar’s more explicit works. “Foreigners are more liberal, but for most collectors like me, art is something that can be displayed in one’s home. Those works I could not,” says Aggarwal.

In the growing culturally intolerant fabric of India, when artistic freedom is increasingly being threatened, would Khakhar have managed being defiant? “Bhupen negotiated very adroitly with his audience, and was adept at camouflaging the radical and transgressive nature of his art. Mob censorship and social stigma were active during his lifetime too, and yet he found ways around this, by braiding the transgressive and the sacred, especially in works like Seva and Yagnya Marriage. He would have figured out a playful yet politically astute strategy to present his work, without any compromise, in the current moment, too,” says Hoskote.

Intimate Geometries: The best of Bhupen Khakhar

Man Leaving (Going Abroad) (1970): In this early work, Khakhar painted two grey-haired men bidding adieu to each other, as one of them sets out on a journey.

Muktibahini Soldier with a Gun (1972): Bespectacled and wearing a white vest, Khakhar’s depiction of a Bangladeshi “freedom fighter” was not a macho figure but someone who seemed vulnerable. Holding a gun against his chest, he overlooks scenes from the street.

Other artwork on display at the Swaraj Art Archive.

Other artwork on display at the Swaraj Art Archive.

The De-Luxe Tailors (1972): Sold for Rs 9.5 crore at a Sotheby’s auction in October 2017, the work belongs to Khakhar’s Tradesmen series. Formerly in the collection of his friend and fellow artist Howard Hodgkin, the oil painting depicts a tailor at work.

Man with a Bouquet of Plastic Flowers (1976): The central figure of a solemn man holding a bouquet of plastic flowers was placed within calendar art.

Death in the Family (1978): Painted after Khakhar visited Sivakasi in south India, the work has a body suspended in the sky, looking down at people bathing after the funeral.

You Can’t Please All (1981): Based on an Aesop’s fable, this is often cited as Khakhar’s “coming out” painting.

The Celebration of Guru Jayanti (1980): The devotees of the Guru occupy a corner in this Khakhar composition where he presents a detailed landscape of the town.

Yayati (1987): A scene from the Mahabharata where an ageing, impotent king asks his son for the gift of youth and virility. Khakhar, depicts himself as a young angelic lover to his older partner.

May 08: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05