- India

- International

Why the Chipko movements was truly a people’s movement

Historian Shekhar Pathak’s book connects Chipko to 19th century colonial environmental laws and modern regional politics

Tree-huggers: Chipko was a grassroots movement that spread throughout Uttarakhand

Tree-huggers: Chipko was a grassroots movement that spread throughout UttarakhandWhen most people think of the Chipko movement, the primary image that comes to mind is of a group of village women in the Himalaya, hugging trees to protect them from felling by forest contractors. While that was the key moment when Chipko ignited, eminent historian Shekhar Pathak successfully unravels many other tangled threads of a story that is much more complicated, with far-reaching consequences for the people and forests of Uttarakhand, as well as conservation movements around the world. This carefully researched history draws upon official documents, published works, press reports, lyrics of protest songs and hundreds of personal interviews with all of the main protagonists. Translated by Manisha Chaudhry and edited by Ramachandra Guha, it is a condensation of Pathak’s Hari Bhari Umeed, the original Hindi edition published in 2019 by Vani Prakashan.

This environmental epic begins long before the events in Reni village on March 26, 1973, when Gaura Devi and a group of women held off agents of the Symonds sporting goods company who had been given a permit to cut a grove of ash trees that were destined to be turned into hockey sticks. The roots of Chipko stretch back to the mid-19th century, when the renegade timber baron, Frederick “Pahari” Wilson, clear-felled virgin forests in the Bhagirathi Valley and floated logs down the Ganga. Colonial forest policies placed a high commercial value on Himalayan species of trees like deodar and pine, as well as sal and shisham, at lower altitudes. One of the primary reasons for deforestation in the 19th and early 20th century was the expansion of the Indian Railways, which required thousands of miles of new tracks, all of which were laid upon wooden sleepers. In one of the largest land grabs in history, the Indian Forest Act of 1878 usurped vast tracts of uncultivated land throughout the subcontinent. Suddenly, forest dwellers were dispossessed of their ancestral rights and livelihood while pastoral and agricultural communities faced restrictions on gathering firewood and fodder as well as felling trees to construct farm implements and homes.

In Uttarakhand, deforestation has severe consequences since trees in the mountains are critical to stopping erosion and nurturing springs and wetlands. Realising the quick profits to be gained by cutting Himalayan jungles, the Maharajah of Tehri began to exert control over forests in his kingdom. This led to a number of protests or “dhandaks”, which ended in violent reprisals. Perhaps, the most famous and oppressive of these was in Rawain, where Pathak estimates as many as 100 villagers were shot by the forces of Tehri in 1930. This resulted in further protests organised by the Gandhian leader Sri Dev Suman and other political activists.

The Chipko Movement: A People’s History By Shekhar Pathak

The Chipko Movement: A People’s History By Shekhar Pathak

Following India’s independence and the absorption of princely states like Tehri, the Uttar Pradesh forest department continued to manage forest resources on the colonial pattern, with an eye to generating revenue for the state. The Himalayan foothills contained the largest tracts of trees and these were auctioned off for timber and resin extraction, as well as pulp wood for manufacturing paper. One of the points Pathak emphasises is that forests remain essential resources for the people who live in and around them. Agriculture, animal husbandry and forest-based crafts are all dependent on the presence of trees as well as other plants and grasses.

Just as he paints a detailed picture of the decades of forest-rights agitation that preceded the pivotal protest in Reni, Pathak recounts and analyses the many events that followed in different parts of Uttarakhand. Organisations like the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Sangh, under the leadership of Sarvodaya activist Chandi Prasad Bhatt, were energised by the early successes of Chipko and took the movement forward. Gandhian environmentalists Sunderlal and Vimla Bahugana also fought to keep ecological issues at the forefront. These celebrated leaders represent what Pathak calls two “streams” of Chipko but there were many others as well. Numerous protests were organised by women in different parts of Uttarakhand, resisting state-sanctioned deforestation, such as harvesting wood from the Bhyundar Valley to make charcoal for the Badrinath temple.

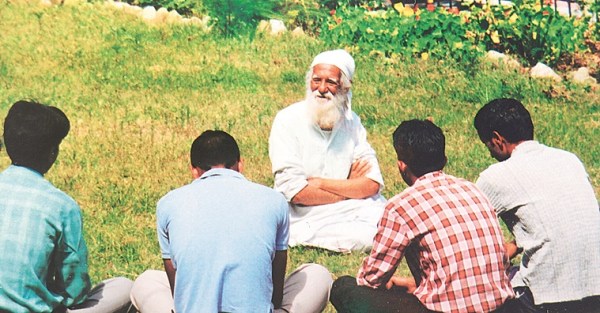

Sunderlal Bahuguna at New Tehri

Sunderlal Bahuguna at New Tehri

The book does an excellent job of showing how a variety of agitations merged together in Uttarakhand, much like the many tributaries of the Ganga. Venerable Gandhians like Sarla Behn were pushing for alcohol prohibition as well as forest rights, while students were demanding the establishment of universities in Kumaon and Garhwal. Pathak himself was one of the leaders of an influential padyatra (foot pilgrimage) campaign from Askot to Arakot, which studied first-hand the social and environmental needs of mountain communities. Meanwhile, construction of the Tehri Dam aroused considerable opposition and helped focus environmental concerns. All of these movements fed into an underlying demand for separate statehood voiced by political groups like the Uttarakhand Kranti Dal.

Though politics and policy lie at the core of this book, there are many poignant, human stories that Pathak relates such as a non-violent agitation in Nainital in which the poet Girish Tiwari “Girda” led a procession in song to stop a forest auction. The book contains anecdotal accounts of wives turning against their husbands who supported the felling of trees and one boy who refused to eat at home until his father gave up a job with a forest contractor. There is also an episode from 1979, when Chandi Prasad Bhatt visits Sunderlal Bahugana, who has taken a vow of silence while fasting in protest at Dehradun Jail. Setting aside ideological differences, the two leaders greet each other with affection and acknowledge that they share the same struggle despite differing visions of Chipko.

The subtitle of this book is “A People’s History”, which is one of its strengths. It documents a grassroots movement that spread throughout Uttarakhand and captured the imagination of people of all ages and regions. The validation of that struggle lies in the Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980, which bans the felling of trees anywhere above an altitude of 1,000 m. The other important outcome was the creation of Uttarakhand state on November 9, 2000. Pathak argues convincingly that the Chipko Andolan played a central role in both of these seminal achievements but he cautions that many threats still remain, including complacency, corruption and climate change.

Stephen Alter is the author of Wild Himalaya: A Natural History of the Greatest Mountain Range on Earth

May 14: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05