- India

- International

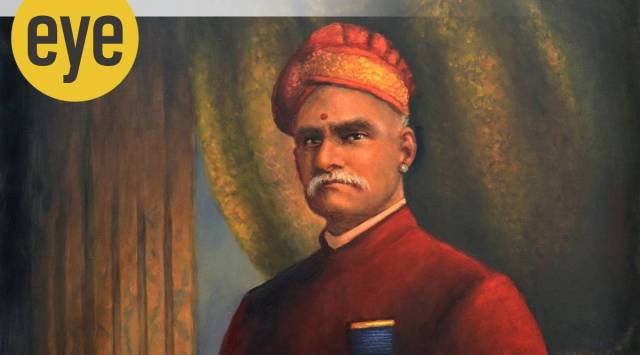

On his 175th birth anniversary, remembering the life and legacy of Raja Ravi Varma

Considered the father of modern Indian art, Varma was arguably the first to successfully combine Indian iconography and portraiture with Western realism and techniques. He was one of 20th century India’s earliest cultural ambassadors

Raja Ravi Varma Portrait by Rukmini Varma. (Pic source: Rukmini Varma)

Raja Ravi Varma Portrait by Rukmini Varma. (Pic source: Rukmini Varma) At Louvre Abu Dhabi, in an exhibition that investigates the origins of Indian cinema, alongside costumes and props from iconic Bollywood movies, are 19th century chromolithographs of Lord Krishna, goddesses Lakshmi and Mohini, painted by Raja Ravi Varma. Gitanjali Maini, managing trustee and CEO of the Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation (RRVHF), points out how Varma not just humanised the deities that previously predominantly rested in temples, but also influenced Indian visual culture and cinematic aesthetics of the time. “(Filmmaker Dadasaheb) Phalke had worked at the Raja Ravi Varma press, and several of his earlier films — such as Raja Harishchandra (1913), Kaliya Mardan (1919), Nala-Damayanti (1927) — were visibly influenced by how Ravi Varma drew his characters; the costumes and characterisation were identical; he made them three-dimensional. In some ways, he brought the still images to life, playing out mythological stories that had previously been seen in Ravi Varma paintings,” says Maini.

Room 2a. January 30, 2023 – Museography technical documentation of the temporary exhibition “Bollywood Superstars”, which runs from 24 January 2023 to 4 June 2023, at the Louvre Abu Dhabi on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Room 2a. January 30, 2023 – Museography technical documentation of the temporary exhibition “Bollywood Superstars”, which runs from 24 January 2023 to 4 June 2023, at the Louvre Abu Dhabi on Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Considered the father of modern Indian art, Varma was arguably the first to successfully combine Indian iconography and portraiture with Western realism and techniques. While his wide spectrum spanned from studio-style portraits of aristocrats and maharajahs to images of deities, his far-reaching imprint has influenced diverse fields, from art and literature to advertising, textiles and the comic book series Amar Chitra Katha. In his 175th birth anniversary year, which began on April 29, there are demands to confer a Bharat Ratna, the country’s highest civilian honour, on the artist.

Folklore has it that Varma was on his way back to Kilimanoor in Kerala from a pilgrimage to Mookambika Temple in Kollur, Karnataka, when KP Krishna Menon, a sub-judge in Mangalore, approached him for a family portrait in 1870. Only 22 at the time, by accepting the commission Varma was taking his first step as a professional artist. “Coming from an aristocratic family, it was unusual for him to have decided to become a professional artist, a career that wasn’t held in high regard when compared to the West,” says Jay Varma, son of Rukmini Varma, great-great granddaughter of Varma.

Narasimha (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Narasimha (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

By this time, however, he had already built a considerable reputation in Travancore, where he had been practising at the royal court since the age of 14, after his maternal uncle Raja Raja Varma, his first teacher, introduced him to Ayilyam Thirunal, the ruler of the princely state of Travancore. Patronised by him, Varma trained under the court painter and was also given access to artworks and books in the palace collection. It is also here that he came in contact with Dutch artist Theodore Jensen, who was reluctant to impart detailed lessons but did permit the young artist to observe and learn as he painted. This is believed to have introduced Varma to the clever use of the chiaroscuro technique, the interplay between light and shade, that he later used not just as a tool for pictorial realism but also to depict spatial relations, adding depth to flat surfaces and bringing his protagonists to life. “No other Indian painter, till today, has been able to supersede Varma in portraiture in oil, a foreign medium, which the artist mastered over time through trial, error and hard work, while understanding the blending, smoothening and the play that was possible with this slow drying substance… (Now) all this excitement over oil and impasto techniques appears excessive… a hundred years back it was like a discovery for an almost self-taught artist,” wrote art conservator and author Rupika Chawla in a publication accompanying the landmark exhibition “Raja Ravi Varma: New Perspectives” at the National Museum in Delhi in 1993, curated by Chawla and artist A Ramachandran.

The Coquette (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

The Coquette (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Born to a Sanskrit and Ayurveda scholar father and a poet-writer mother, Varma was inclined towards the arts from early on. There are accounts of a young Varma scribbling on the walls of his home with charcoal as a child and someone constantly wiping it off to ensure that he could start anew on a blank wall.

At 18, the artist married Bhageerathi Bayi of the royal house of Mavelikara in Kerala, strengthening his ties further with the royalty. Given a studio in the palace to paint, the fast-expanding railway network gave Varma the freedom to travel extensively with his brother C Raja Raja Varma to explore opportunities and patronage across India. “The turn of the century was the first phase of the advance of information technology. The British brought the railways, followed by the wireless telegraph system, newspapers. The kerosene lamp arrived in India, and a little later, Mysore got electricity. All these inventions either came into his lifestyle or art… For instance, he had a woman reading a newspaper, imparting two messages, one is literacy among women and the other is that the postal system has arrived, so it is important to read the subtext… He was certainly a man ahead of his times,” says Chawla. Jay adds, “Till that time, no one had painted Indian scenes the way he did; even European versions of India were very Western. He was able to bring an Indianness with the kind of realism he pursued.” “There was a long period of struggle to get to the point where he could work independently,” says author-playwright Shreekumar Varma, the artist’s great great grandson.

Mohini (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Mohini (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Over the years, as his wide network of patrons expanded, he also forged influential friendships and built significant associations. If Raja Deen Dayal, celebrated court photographer of the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, extended to him an invitation to visit Hyderabad, Fatehlal Mehta (son of Rai Pannalal Mehta, a retired minister from Udaipur, whose portrait was painted by Varma) introduced him at the court of Maharana Fateh Singh. Sir T Madhava Rao, Diwan of Travancore and later Baroda, was instrumental in forging close ties between the artist and Sayajirao Gaekwad III, who gave him one of his most celebrated commissions, offering him a princely sum of Rs 50,000 in 1891 to produce 14 paintings depicting scenes from Indian epics for the Durbar Hall of Lakshmi Vilas Palace at Baroda. Assisted by his brother, the suite of paintings caught immediate public attention when exhibited in Bombay before reaching Baroda.

The reception strengthened Varma’s desire to reach out a larger audience and led to the establishment of India’s first lithographic press in Bombay. With machinery imported from Germany and operated by two German litho-transfer artists, Fritz Schleicher and B Gerhardt, in July 1894 it produced its first oleograph, The Birth of Shakuntala, followed by Lakshmi and Saraswati, sold for less than a rupee. Though the constant demand saw it operate at a capacity of 800 impressions an hour, following the 1896 Bombay plague and subsequent shortage of staff, the operations shifted from Girgaum to Malavli.

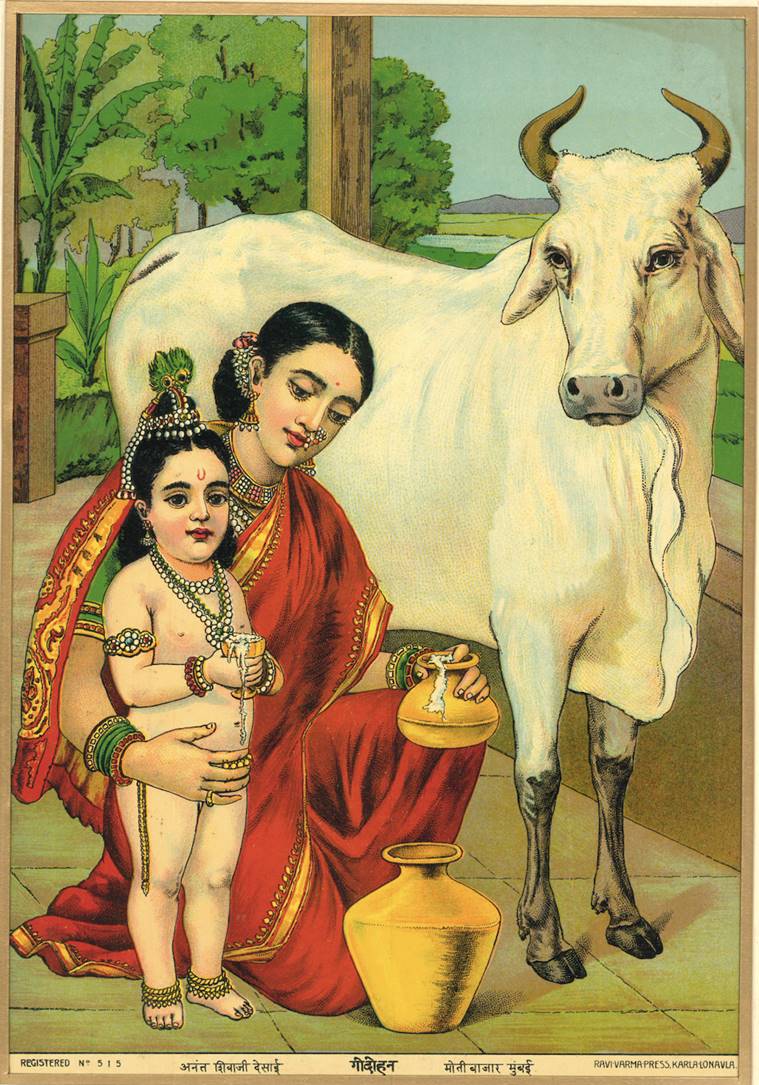

Godohana (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Godohana (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

However, when Varma’s business partner Govardhandas Khatau Makhanji exited the partnership, the artist, who was constantly travelling, found it difficult to enforce stringent financial vigilance and control incidence of piracy. In 1903, the press was sold, along with the copyright for over 100 of his paintings. While the reproductions travelled beyond the Indian subcontinent, within the domestic confines, they played a significant role in creating a pan-India religious iconography that helped democratise the gods whose worship in the class and caste-stratified society was the privilege of a few.

In the early 20th century, Varma could easily be counted as one of India’s finest cultural exports. Estimated to have made over 2,000 oil paintings, in 1873, his work Nair Lady Adorning her Hair, depicting a woman with a jasmine garland, was awarded with the Governor’s gold medal at the Madras Fine Arts Society Exhibition. In 1893, he represented India at the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in conjunction with the first Parliament of the World’s Religions, where Swami Vivekananda was a speaker. The prestigious showcase featured 10 of his paintings depicting women from across India, from a Parsi bride to an aristocratic Muslim to a young Hindu woman. In 1904, the Imperial government awarded him the Kaiser-e-Hind medal for public service. Referring to the award, in his diary, his brother Raja Raja Varma reportedly wrote: “The honour bestowed on my brother came without our seeking. We never spoke to anyone about it nor have we worked for it… This is the first time an artist is honoured in India’s history. The honours so far were given to officials and rich men who donated liberally to charitable causes…”

Lakshmi (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Lakshmi (Pic source: Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation)

Ironically, soon after Varma’s demise in 1906, there was extensive renunciation of his work, particularly in the wake of the Swadeshi movement. Accused of aping the West and adapting European techniques and materials that were anti-nationalistic, he was denounced by the philosopher Sri Aurobindo, the Tagore family and metaphysician Ananda Coomaraswamy, among others, for producing, what was termed as “calendar art”. This perception continued through the 20th century, until more recent re-readings ascertained how the modernist blended various influences and traditions — from Tanjore art to temple murals to European realism, music and literature in Malayalam, Sanskrit and English. “Over the years, he has been a part of public discourse. His works have appeared on matchboxes, soap advertisements. There have been songs mentioning his paintings in Malayalam and Tamil… Now, it is only percolating further… So many of his unknown works are still being discovered,” says Shreekumar.

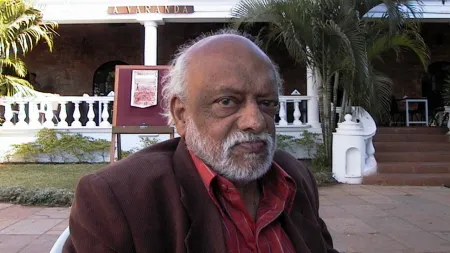

Rupika Chawla (Pic source: Rupika Chawla)

Rupika Chawla (Pic source: Rupika Chawla)

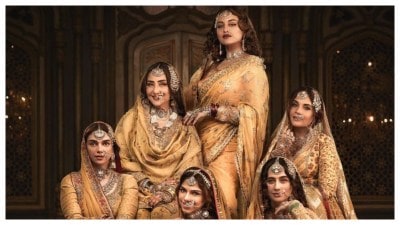

As his works continue to pervade popular culture, there have also been contemporary interpretations. If artist Nalini Malani referenced his allegorical painting Galaxy of Musicians in her 2003 video installation Unity in Diversity, Bengaluru-based Pushpamala N recreated three of his paintings with herself as the protagonist in a 2000-2004 series. Photographer G Venket Ram brought some of his acclaimed paintings to life in his 2020 calendar, with actors and dancers such as Samantha Akkineni, Shruti Haasan and Ramya Krishnan posing as his protagonists.

The commercial success, meanwhile, is evident from the prices he has fetched at international auctions despite the ban on the sale of his works outside India since they are classified as “national treasures”. In 2017, an untitled portrait of Damayanti was auctioned in New York for Rs 11.9 crore, and in 2016 his oil on canvas titled Radha In The Moonlight sold for Rs 23 crore. Last year, some of Varma’s works were also auctioned as non-fungible tokens at an online art marketplace RtistiQ in partnership with RRVHF. “With NFTs becoming a phenomenon, we wanted to explore the digital possibilities with his works and take them to the younger generation,” says Jay.

Varma had been preparing for a grand celebration of his 60th birthday, for which, according to Shreekumar, he intended to invite a large gathering to Puthen Malika, designed by him in Kilimanoor. But the death of his brother and his own tryst with diabetes broke his spirit. Varma passed away at 58, leaving incomplete another project dear to him — a museum to house his artwork. “He had filled his house in Kilimanoor with paintings. Some of the works at the Sree Chitra Art Gallery (in Thiruvananthapuram) have labels that were placed to catalogue paintings for the museum… He knew that everybody could not own his paintings but he certainly aspired for them to be able to see them,” says Chawla.

Buzzing Now

May 03: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05