- India

- International

A River called Ritwik

Ritwik Ghatak's films stand out for their stark depictions of social and cultural displacement.

Ritwik Ghatak’s films stand out for their stark depictions of social and cultural displacement. As a Bengali movie inspired by his life releases this week,we piece together the portrait of an eccentric auteur and his struggle for acceptance

On the morning of February 7,1976,when Calcutta woke up to the news of Ritwik Ghataks untimely death the previous night,stunned citizens poured out onto the streets. Barely three months ago,the auteur had turned 50. When the funeral procession started from the Presidency General Hospital in the afternoon,thousands singing Ghataks favourite songs,trailed the vehicle that carried his body to the burning ghat in Keoratala. In an essay titled The Genius that was Ritwik Ghatak,the late theatre artiste Safdar Hashmi recorded the outpouring of grief in what he called a unique funeral of a unique man.

Thirty-seven years later and 60 years since he made his first movie Nagarik (1952),Ghatak remains one of the most underplayed cinematic legends of India. He was a flawed genius erratic,eccentric,and impulsive to the point of being self-destructive. Ghatak was an anarchist. Yet,he remains the most authentic voice in Indian cinema. Despite his lack of formal grammar in moviemaking,his works remain highly relevant today, says Nabarun Bhattacharya,Sahitya Akademi award-winning Bengali author. Bhattacharya is also the son of Ghataks close associate Bijon Bhattacharya and writer Mahasweta Devi,the filmmakers niece.

Ghatak made eight features and 10 documentary films. Three of his full-length films were released after his death. This includes his first film Nagarik (1952) which he made at 27 nearly three years before Satyajit Ray made his first film Pather Panchali,which ushered in a new era in Indian cinema. Nagarik,the story of a young man in search of a job in post-war Kolkata and his gradual degradation,is as powerful a movie,but it never released in its time,robbing Ghatak of a chance to pioneer the movement for alternate cinema. The print of the film,which was apparently lost,was restored and released around the same time as Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974). By the time these films reached theatres,Ghatak was no more. Even his Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973),which was produced by Habibur Rahman Khan of Bangladesh,was shown in India after his death. Prior to this,Subarnarekha (made in 1962),one of his most celebrated films,too had to wait for three years for release.

While alcoholism and tuberculosis hastened his death,not being able to show his movies broke his heart. This great filmmaker was neglected all through his life by bourgeoise critics,hounded by the establishment and crushed by those who controlled the film industry, wrote Hashmi,terming the censure as a long physical suppression of Ghataks work.

Ritwik suffered a lot. His main anguish was not being able to show his films to the public, says Surama Ghatak,his 86-year-old wife,who lives in Kolkata’s Chetla. Apart from delayed releases,several projects that he started,were left incomplete,mainly due to lack of funds or differences with producers. Feature films,Bedeni,Bagalar Banga Darshan and Ronger Golam,and documentaries on sculptor Ramkinkar Baij and Indira Gandhi are some such instances. Bagalar… and the documentary on Baij were completed by his son Ritaban later on. His refusal to acquiesce to market forces and his inability to be diplomatic worked against him. An arrogantly committed and forthright man,he had alienated many people by his strong sense of conviction and feeling, wrote filmmaker Kumar Shahani in a 1970 essay on Ghatak. Later,in another essay in 1981,he wrote,Ghataks cinematography belonged to the world.

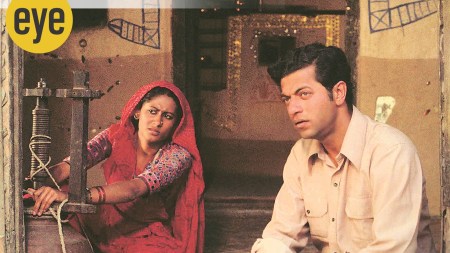

Ironically,the filmmaker,whose long-drawn struggle to complete movies and exhibit them,made a return of sorts to theatres in Bengal this Friday. Through Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star),a Bengali movie written and directed by Kamaleswar Mukherjee,there is an attempt to relive his life and philosophy on the big screen. The movie uses the same title as that of Ghataks masterpiece made in 1960. A story of a migrant Bangladeshi family in West Bengal,it had Supriya Choudhury as the sacrificing Nita,who toils for her familys comfort and dies of tuberculosis. As described by her on-screen lover,she remains the star hidden by clouds.

The new Meghe Dhaka Tara,featuring Saswata Chatterjee (now famous as Bob Biswas of Sujoy Ghoshs Kahaani) as Neelakantha Bagchi named after the lead character of Jukti Takko Ar Gappo,Ghataks last completed film shies away from calling it a biopic. In 1969,Ghatak was sent to the asylum in Gobra. There,he wrote and directed a play in which the inmates of the asylum acted. My movie opens with that and travels back and forth, says Mukherjee,who confesses to being intrigued by Ghataks personality. He was a non-conformist and an erratic genius. My film,though based on him,is partly fictionalised, he says. The film with subtitles is slated to have a pan-India release on June 28.

Mukherjees unit shot the film in West Bengals Purulia in May 2012. To prepare for the role,Chatterjee watched Jukti Takko Ar Gappo in which Ghatak had cast himself as Neelakantha Bagchi. Reed-thin Ghatak,clad in a loose kurta-pyjama,with unkempt salt-and-pepper mop,thick-rimmed glasses and a bottle of country liquor in hand,acted in this movie his most autobiographical film as well as a commentary on the contemporary social and moral degeneration. For Chatterjee,playing the Ghatak-inspired character required deep understanding of the maverick filmmaker. It was a difficult role. I had to study his mannerisms and analyse them, says the actor,who says he prepared for the part for months. By the time,he finished shooting and dubbing,his wife was pointing out the Ghatak mannerisms he had imbibed during the shoot.

Bhattachaya was young when he accompanied his father to Ghataks sets and outdoor shoots. Yet,he retains an image of Ghatak consumed by a divine passion for cinema. He was adept at every aspect of moviemaking. He was a brilliant cinematographer and had a great sense of music. He used to play the flute, says Bhattachaya,who was introduced to western music by Ghatak with Night on Bald Mountain,a composition by Russian Modest Mussorgsky. Ghatak even tried to master the sarod under the tutelage of Ustad Bahadur Khan.

Kolkata-based filmmaker Arin Paul,who has been researching Ghatak for three years,recounts cinematographer Ramananda Senguptas experience with Ghatak. While shooting Nagarik,Sengupta followed Ghataks instructions and frames. When showered with compliments for its wonderful low-angle shots,he had Ghatak to thank for them.

Yet,what set Ghatak apart at a time when Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen were producing great works in Indian parallel cinema is his use of melodrama. That was,perhaps his biggest takeaway from theatre. The penultimate scene in Meghe Dhaka Tara,where Nita tells her brother: Dada,ami bachte chai (I want to live),shows his mastery over melodrama. For this,however,he had forbidden Choudhury from shedding tears. Instead,he had asked her to cry out loud.

Throughout his film career,Ghatak struggled to find financiers,equipment and other support. In a documentary on the filmmaker,actor Anil Chatterjee,who played Sankar in Meghe Dhaka Tara,recalled that while filming the song sequences featuring him,they did not have a playback machine. Vocalist AT Kannan had sung the films classical songs. Since lip-syncing was a challenge without the machine,an IPTA artiste used to sing from a distance and I used to follow him to perfect the lip movement, he said. But then,such innovations,he said,were common practice on Ghataks sets.

Today,Ghatak is feted internationally his films are being screened at film festivals and studied as expositions of his time. Author Rinki Roy Bhattacharya,daughter of filmmaker Bimal Roy,says,He is not forgotten,especially abroad. In 1987,during what could be Titas Ekti Nadir Naams first international screening at a festival in Italy,she did a live translation of its dialogues in English. The audience response to the movie was rousing, she says. This,perhaps,validates Ghataks own prophecy. In spite of setbacks,my father was always optimistic. A few days before his death,he consoled me saying that his films were going to be appreciated,but after his death, says his daughter Samhita,who has recently published a book on him called Ritwik Ekti Nadir Naam (A River Called Ritwik).

Filmmaking was not Ghataks initial choice as a career. By his own admission,he strayed into films down a zigzag path. In an interview,he once said that his father wanted him to be an income-tax officer. He got the job but quit to join the Communist Party of India (CPI). He also wrote a cultural thesis called On the Cultural Front,which talked about mobilising the masses through art and theatre,and submitted this to the party in 1954. The then CPI leadership did not agree with his proposed policy and it languished till 1993.

Before he found his calling in movies,he tried his hand at writing poetry and short stories. When he joined the Indian Peoples Theatre Association (IPTA) and discovered theatre,he had an epiphany. This is where he met a number of his later associates,including his wife. After a very active stint with IPTA when he handled all aspects of stagecraft including lighting,acting,writing and direction he switched to cinema. The medium,he felt,would best convey the reality around him,enabling him to reach out to a large audience. His desire to tell his stories to a wider viewership was so overwhelming that once television came into the scene,he wanted to kick cinema out and turn to TV.

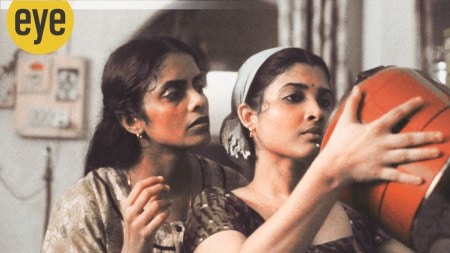

For Ghatak,cinema was an extension of his personality. He was born in Dhaka in 1925 and moved to Kolkata when he was 19. Uprooted from his birth country,he always yearned for it. His personal trauma of being a refugee and the struggle of other refugees from Bangladesh,who migrated during the famine in 1943,the partition of Bengal in 1947 and the War of Liberation in 1971 have been the subject of most his movies, says Sudipto Basu,a documentary filmmaker who assisted Ghatak for nearly a decade. Known as Ghataks refugee trilogy,Meghe Dhaka Tara,Komal Gandhar (1961) and Subarnarekha,remain moving images of human struggle. He returned to Bangladesh many years later to make Titas Ekti Nadir Naam.

The story of Ghataks troubled legacy revolves around alcoholism. This was also speculated to be the reason behind his wife leaving Kolkata and taking up a job at a school in Birbhum. Initially a teetotaller,he started drinking an occasional beer while making Ajantrik. When Komal Gandhar (considered to be a requiem for IPTA days) failed to make a mark at the box-office,he started drinking more frequently. Initially,I did not realise it. Soon,he started consuming country liquor, says Surama. He also used to smoke copious beedis. At his Bhawanipur residence,there used to be a pot filled with stubbed beedis,remembers Basu. He used to turn up slovenly and drunk at our house in Bombay. I used to be scared of him, remembers Roy Bhattacharya.

During his lifetime,the biggest validation of his genius came from his students at Film and Television Institute of India (FTII),Pune. There he taught direction between 1962-67 and set the curriculum. He even served at its vice-principal for two years. Ritwiks students adored him. His lifestyle was bad but his teaching style had a strong appeal on them, says Roy Bhattacharya. According to PK Nair,former director of National Film Archives of India (NFAI),what made him popular was his non-regimented approach to teaching. He once woke up students at 4 am and took them to the Shantaram pond on the campus to watch the sun rise and study light, Nair remembers. Some of his famous students were parallel filmmakers Kumar Shahani,Mani Kaul,Adoor Gopalakrishnan and the Kerala-based John Abraham.

At FTII,he was surrounded by students most of the day. Ghatak used to regularly conduct his classes under a tree on the campus,known as the Wisdom Tree. He held discussions and debates with them after watching movies at 6 pm and 9 pm. I used to choose the films for these evening screenings, says Nair,who used to share a flat with him then. In fact,Shahani once said,In a sense,it was through the adulation of the young that Ghatak and the country rediscovered his work. I remember the unusual childlike incredulity,his helplessness for loving approbation when the FTII first saw and applauded Komal Gandhar.

Though most of Ghataks movies are dark,he made a delicious deviation with Bimal Roys Madhumati (1958),for which he co-wrote the script. It was a story of reincarnation peppered with murder,suspense and supernatural elements. He did not have much faith in its success. During a break from shooting,he apparently joked that this will cause the death of a capitalist filmmaker referring to my father, says Roy Bhattacharya. The film was a huge hit and its story has been copied several times in Bollywood over the years. He also wrote the script for Hrishikesh Mukherjees Musafir (1957). For some months,he worked at Filmistan in Bombay for Rs 300 a month and later,even assisted Roy.

But the glamour of Bombay could not hold him back. Kolkata brought out his cinematic best,even if they were stories of the break-down of moral values. He reacted passionately to this,remaining one of Indian cinemas most authentic and incisive social commentators.

May 20: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05