- India

- International

Thirty-two winters ago, the hookah, the hukumat

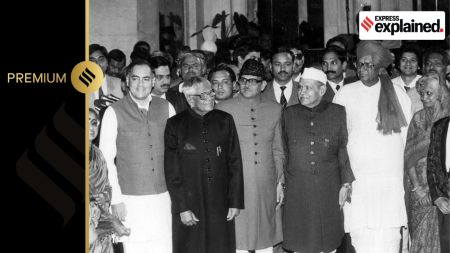

For a week beginning October 25, 1988, nearly 500,000 farmers took over the heart of the Capital, occupying Boat Club and its lawns, within earshot of North and South Blocks, and Parliament where the winter session was to start days later.

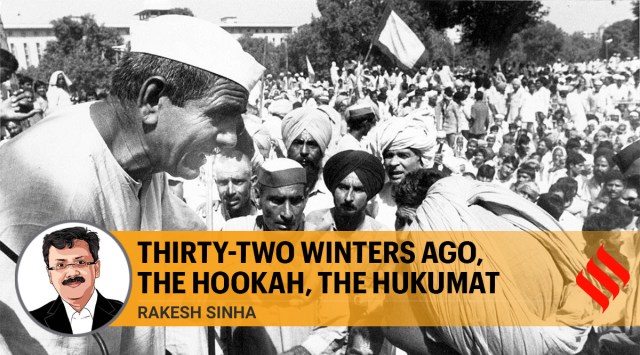

Mahendra Singh Tikait with farmers from western UP on the Boat Club lawns, during a protest that lasted a week in October 1988. (Express Archives)

Mahendra Singh Tikait with farmers from western UP on the Boat Club lawns, during a protest that lasted a week in October 1988. (Express Archives)At first, there was a trickle. Within hours, that trickle became a flood as tens and thousands of farmers — on trucks, tractor-trolleys, bullock carts, motorcycles — showed up at the gates of Delhi. And camped to press their case.

Thirty-two winters before farmers from Punjab and Haryana began their sit-in at the borders of Delhi, Bharatiya Kisan Union leader Mahendra Singh Tikait mobilised farmers of western Uttar Pradesh and headed to the country’s seat of power, determined to get them their due.

For a week beginning October 25, 1988, nearly 500,000 farmers took over the heart of the Capital, occupying Boat Club and its lawns, within earshot of North and South Blocks, and Parliament where the winter session was to start days later.

Curious, surprised and somewhat bewildered, many in Delhi had no clue why the farmers were here — this was still the era of government-controlled news via Doordarshan and All India Radio, and people had to tune into BBC or wait for the morning newspaper for information. There was no 24X7 TV, no private television network, no Internet, no mobile phone.

Tikait and his men wasted no time in disseminating information. They held huddles with reporters, morning to night, patiently explaining each of the 35 demands they hoped that the Rajiv Gandhi government would concede. There was a litany of complaints — of agrarian distress, delayed payments, complicated bureaucratic rules, and an administration cold to their suffering.

Loudspeakers too listed their demands, the emphasis more on a higher price for sugarcane produce, waiver of dues, concessions in electricity and water tariff.

Yet these demands were not new, and Agriculture Minister Bhajan Lal knew that. Because nine months before he showed up in Delhi, Tikait had staged a similar sit-in outside the office of the Meerut divisional commissioner, with the same demands for the Vir Bahadur Singh government in Lucknow.

Several consultations later, Singh had invited the BKU to Lucknow. But Tikait had other plans. Delhi was closer than Lucknow, and he knew that a bigger Congress government sat there, one that had control over Uttar Pradesh.

The October siege of Delhi was an extension of the BKU’s Meerut campaign. It also signalled the arrival of Tikait on the big stage as many thought he would fill a vacuum in western UP. Its tallest leader and the country’s fifth Prime Minister, Chaudhary Charan Singh, had been incapacitated by a stroke in November 1985 — he passed away 18 months later — and the region yearned for one worth his salt.

In Lucknow too, there had been a change of guard. In June, months after the Meerut sit-in, Singh had been replaced by N D Tiwari, the man he had succeeded as Chief Minister, and was called to Delhi where he was made Minister of Communications in the Rajiv government.

By then, western UP was restless, and bristling. So when the call came from Sisauli, Tikait’s home near Muzaffarnagar, hundreds trooped out of every village.

At Boat Club, as the farmers sat out nights, policemen kept watch. There were attempts to wear them out. Every trick in the book was employed — loud music, at times western, was played at night, hoping this would unsettle the farmers and their cattle, and make them leave; water supply in and around the area was stopped, so was delivery of food packets to feed the vast gathering.

But that only steeled their resolve. And the tide began turning in Delhi. Already unpopular because of the Bofors scandal and the resignation of V P Singh, Rajiv Gandhi and his government came under pressure. The fact that the BKU was not letting politicians take the stage to address the farmers — at that point, Tikait wanted to keep it purely apolitical — didn’t go unnoticed, and there were editorials on the hookah and the hukumat as public sympathy slowly began gravitating towards the farmers.

On October 31, a week into the sit-in, the Congress moved its rally on the anniversary of Indira Gandhi’s assassination to the Red Fort grounds, away from Boat Club. The very next day, Tikait lifted the siege of Delhi. There was no formal agreement although concessions were assured. The following year, before the Lok Sabha elections, N D Tiwari signed a pact with the BKU, conceding many of its demands.

Etched in the collective memory of Delhi, Boat Club had a message. Participating in a parliamentary debate, the BJP’s Hanamkonda MP C Janga Reddy —he and Mehsana’s A K Patel were the only two party candidates to get elected to the Lok Sabha in 1984 — warned the government: “The rally held at Boat Club seven days ago is a precursor of more rallies to come. An agitated farmer means an agitated nation.”

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

May 17: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05