- India

- International

Bribe case to declaring donor, full circle for JMM

Recently, the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha, the ruling party in Jharkhand, chose to go public about the electoral bond donation of Rs 1 crore it received from aluminium manufacturing company Hindalco.

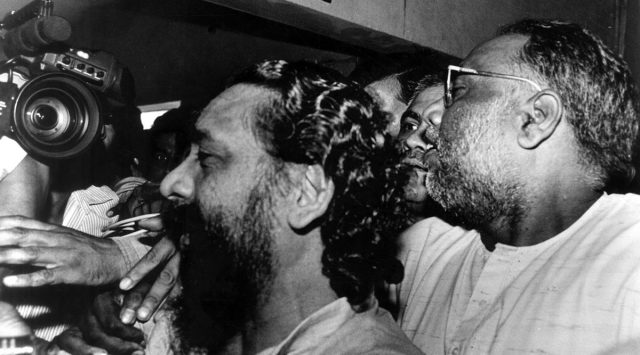

JMM’s Shibu Soren and Suraj Mandal being produced at Delhi’s Tis Hazari Court in connection with the bribery case in 1996. (Express Archive/Arvind Yadav)

JMM’s Shibu Soren and Suraj Mandal being produced at Delhi’s Tis Hazari Court in connection with the bribery case in 1996. (Express Archive/Arvind Yadav)In recent years, electoral bonds have been seen as an alternative to cash donations. Political parties however do not reveal the identity of their donors. Recently, in what was a surprise move, the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha, the ruling party in Jharkhand, chose to go public about the electoral bond donation of Rs 1 crore it received from aluminium manufacturing company Hindalco.

With this step, the wheel has come around a full circle. For, it was the JMM which was charged with taking bribes to bail out the P V Narasimha Rao government in 1993. Indian politics is full of paradoxes and this is one of them.

The famed ‘JMM case’, which went on for years, had far reaching ramifications. It had involved payment of bribes to JMM and other MPs by the then prime minister P V Narasimha Rao in order to cobble together a majority.

The 1991 elections had thrown up a hung Parliament, with the Congress emerging as the single largest party. Narasimha Rao went on to form the government, with the support of regional parties.

Till 1993, he was ably managing the minority government he headed. The temptation to acquire a majority became compelling in mid-1993 and the Congress’s “experts in realpolitik” were drafted to break both the JMM and the Janata Dal headed by Ajit Singh. The JMM affair robbed Narasimha Rao of legitimacy.

Friends had told Rao that he had displayed greater skill at running a minority ministry, managing support from regional chieftains and even the Left leaders, than he did with a government with a majority. But the demolition of the Babri Masjid in December 1992 had unnerved him and more knives were out for him from his colleagues within the Congress like Arjun Singh than from opposition leaders.

A PIL was filed against Rao and JMM MPs, among others. The trial court convicted Narasimha Rao and Buta Singh to three years of rigorous imprisonment. They were later acquitted by the Delhi High Court in 2002. The CBI did not go in appeal against the acquittal, though there was pressure from within the BJP, led by the “Hawala” charged L K Advani, to move against Rao. But Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then prime minister, who had regard for Rao, decided against going in for appeal.

The case also had a huge impact on the JMM MPs. They got embroiled in a matter which they had thought would be a simple affair. They happily went on to deposit the money given to them in their bank accounts at the Nauroji Nagar branch of the Punjab National Bank in Delhi.

Shailendra Mahto, one of the four JMM MPs who had voted to save Rao, later broke ranks with his other three colleagues—Shibu Soren, Suraj Mandal and Simon Marandi. He confessed that they had been paid money by the Congress. He had been won over by the BJP.

Mahto revealed that Buta Singh had taken all four of them to meet Rao two days before the confidence motion. And Rao had assured them that all issues related to the Jharkhand Council that were agitating them would be addressed by him. He urged them to vote in his favour.

The court gave the MPs immunity from conviction. It held that they, as MPs, were public servants, and could not be prosecuted under the Prevention of Corruption Act. This writer remembers some JMM members getting atop a table in the Central Hall of Parliament, holding forth, much to the embarrassment of the others present. This was soon after the no confidence vote, and they were suspected of being “high”.

Later they admitted before the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal that they had received the money. It was not bribe money, they explained, but money “voluntarily” given to them by the Congress for the “welfare of their party” and their state. And they had voted to save the Rao government in “national interest”.

The JMM affair epitomised yet another brush tribal India had with mainland India. Coming from non-monetised economies, though this has changed, the MPs were not adept at handling money. Nor were they fully aware of the implications, of what could follow, given how they deposited the money in banks.

They are “wiser” today. It is another matter that a Madhu Koda (a former CM of Jharkhand) spent years in jail in another case involving corruption while the big daddies behind him escaped unhurt.

In the initial years, BSP founder and Dalit leader Kanshi Ram used to rely on Mumbai industrialist Jayant Malhotra, who he made an MP, to manage his finances. Heartland India can initially be quite overwhelming for those who come from the tribal communities. I remember a Naga friend describing how he had felt when he arrived at Kolkata railway station for the first time, on his way to Chennai to study. “It felt as if mainland India would overwhelm us.”

A large number of tribal communities live in India’s hinterland, on the peripheries of the country’s decision-making processes, which could be enriched by their traditional focus on equity, community and harmony with forests and nature.

Could the JMM’s latest move be a step in bringing a much-needed transparency into our electoral funding or just one of those freak accidents?

The writer is a senior journalist

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

May 09: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05