- India

- International

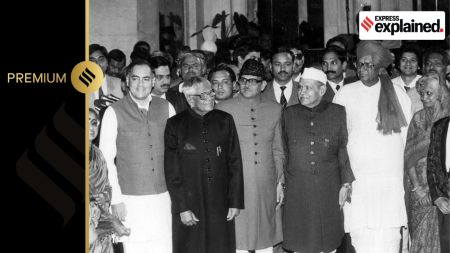

Indira Gandhi as ‘a Hindu first and a Hindu last’, and the grieving mother who blamed herself

Excerpts from a rare insight into the lives of six prime ministers

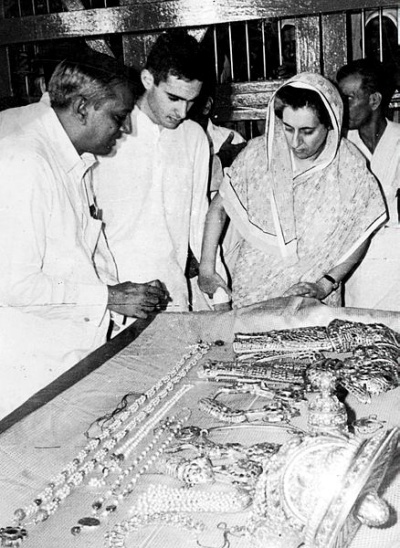

Congress leader Sanjay Gandhi with his wife Maneka Gandhi and mother Indira Gandhi. (Express archive photo)

Congress leader Sanjay Gandhi with his wife Maneka Gandhi and mother Indira Gandhi. (Express archive photo)

How Prime Ministers Decide, a book written by The Indian Express Contributing Editor and columnist, Neerja Chowdhury, reveals rare and untold details from the tenures of Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, V P Singh, P V Narasimha Rao, A B Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh.

Excerpts from two sections in the book:

Hinduisation of Indira Gandhi

‘My sense was that Indira Gandhi turned to this dharamkaram (religious rituals) really for (her son) Sanjay (Gandhi),’ said Anil Bali (the nephew of Kapil Mohan of the Mohan Meakin group), who had come to have easy access to her in the years she was out of power. An astrologer had warned her that Sanjay’s horoscope showed ‘a lifeline cut short’ – this had contributed to her increased temple going after 1977, when she had become overtly religious and paranoid about Sanjay’s safety.

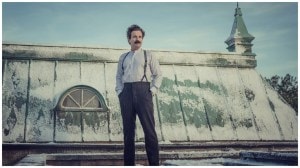

Indira Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi looking at Lord Venkateshwara’s jewels at Tirupati. Express archive photo

Indira Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi looking at Lord Venkateshwara’s jewels at Tirupati. Express archive photo

She had not always been so explicitly religious. In 1966, she took the PM’s oath on the Constitution of India. In 1980, she did it in the name of God. Nehru had been an agnostic; her mother Kamala was a deeply religious woman. She was influenced by both, at various times in her life. When Nehru died in 1964, she decided to cremate him with Hindu rites. She did this despite Nehru’s explicit instructions in his will not to give him a religious funeral. But Indira decided otherwise.

She knew she was defying her father’s wishes. But politicians and religious leaders convinced her that the people of India would not accept a non-religious funeral for Nehru. The pragmatist in her won. She had taken to consulting astrologers during the Emergency.

But it was during her years in the wilderness, from 1977-80, that she really came to be ‘seen as a Hindu first and a Hindu last’.

After she lost power, she visited temples, big and small, obsessively…

Others felt she changed her party’s symbol from the cow and calf to the hand because of Baba Devraha. He was a siddha yogi who lived on a 12-foot-tall wooden platform on the banks of the Sarayu River in eastern UP; he would descend from his perch only for a dip in the river. When she made her way to see him in 1978, the baba came down specially to meet her. He raised both his hands to bless her.

Anandamayi Ma gave her a rare ekmukhi rudraksh, a necklace of 108 brown beads she habitually wore as a kind of talisman to protect her in critical situations. Another spiritual figure she reached out to was Jiddu Krishnamurti. Rajneesh flourished in her time. The Chhattarpur temple in Delhi was built during her tenure. Dhirendra Brahmachari found patronage in her court and taught her yoga.

President Neelam Sanjiva Reddy consoling Indira Gandhi after Sanjay Gandhi’s death. Express archive photo

President Neelam Sanjiva Reddy consoling Indira Gandhi after Sanjay Gandhi’s death. Express archive photo

At home, she had a small puja room. Every day, ‘there would be an offering of 108 flowers’. When she won in the January 1980 elections, and returned to her old home at 1, Safdarjung Road, she conducted elaborate prayers to purify the place. She wanted to remove all traces of the previous occupant, Morarji Desai.

That same year (1980), on 16 February, there was a solar eclipse. Indira asked a pregnant Maneka to retire to her room.

An eclipse was considered inauspicious to the unborn child. Her friend Pupul Jayakar was disturbed to see her become more and more superstitious. Years later, after the June 1984 Operation Blue Star, when she had sent the army into the Golden Temple to flush out the Punjab militants seeking Khalistan, ‘Mrs Gandhi conducted a mahamrityunjay paath at her home for a month,’ said Satyapal Malik. ‘Arun Nehru had personally told me this.’ She was apprehensive that she might be killed.

How Prime Ministers Decide, by Neerja Chowdhury, is scheduled to be published by Aleph next week

How Prime Ministers Decide, by Neerja Chowdhury, is scheduled to be published by Aleph next week

‘Mrs Gandhi was very religious,’ Karan Singh affirmed. ‘She wore different colours of saris on different days (because of religious reasons).’…

Indira Gandhi’s increased temple going was not lost on the RSS leadership.

RSS chief Balasaheb Deoras had once remarked during the course of a conversation, ‘Indira Gandhi bahut badi Hindu hai (Indira Gandhi is a staunch Hindu).’…

In 1971, the RSS praised her for hiving off Bangladesh, and weakening Pakistan. The then RSS chief Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, popularly known as Guruji, wrote to her, ‘The biggest measure of credit for this achievement goes to you.’ In 1974, she won the RSS’s admiration again for exploding the nuclear device – the RSS had always advocated a militarily strong India.

Indira Gandhi’s rightward shift coincided with Balasaheb’s rise as the RSS’s sarsanghchalak in June 1973. By then, she was moving away from her Leftist policies…

Indira Gandhi after Sanjay Gandhi’s death. Express archive photo

Indira Gandhi after Sanjay Gandhi’s death. Express archive photo

The politically savvy Balasaheb wanted to mainstream both the RSS and the Jan Sangh. He used to openly proclaim that he was an agnostic; he would often refer to himself as ‘a communist within the RSS’… Balasaheb encouraged both the Jan Sangh and the ABVP to support the students’ Nav Nirman movement in Gujarat and the Bihar movement led by JP in 1974 against the Congress government.

Sensing the growing unhappiness in the country with the sudden spurt in oil prices and the economic hardships that followed the 1973 Yom Kippur War in West Asia, Balasaheb had advised L. K. Advani, then a rising figure in the Jan Sangh, to sharpen his attacks on Indira Gandhi. But when the Emergency was declared on 25 June, 1975, Balasaheb was impressed, initially, with the ‘discipline’ it sought to inculcate, the safai (cleanliness) it tried to bring on the streets, and the order Indira Gandhi said she wanted to enforce in the country.

Five days after the Emergency, Indira Gandhi jailed Balasaheb Deoras – she banned the RSS and twenty-five other organizations on 4 July, 1975. The RSS leadership decided to support the underground activities of the Lok Sangharsh Samiti (LSS) set up by JP – and helped establish an underground press and mobilize overseas support to resist the Emergency. But soon the RSS leaders decided that, even as its leaders remained in jail, it would try and effect ‘a compromise’ with Indira.

Balasaheb Deoras wrote his first letter to Indira Gandhi from Yervada Jail on 22 August, 1975. He began by praising Indira Gandhi. ‘Your address (on 15 August, 1975, from the Red Fort) was timely and balanced.’ Indira ignored the letter. Balasaheb wrote to her again on 10 November, 1975. This time, he congratulated her on the Supreme Court setting aside her disqualification from Parliament, ordered by the Allahabad High Court on 12 June, 1975.

He also tried to distance the RSS from JP’s movement, which had demanded her resignation. ‘(The) Sangh has no relation with these (Bihar and Gujarat) movements….’

Yet again, Indira did not respond. Balasaheb now appealed to Vinoba Bhave, who had her ear. Balasaheb had learnt that Indira was going to Bhave’s Paunar Ashram on 24 January, 1976. He wrote to Bhave on 12 January: ‘I beg you to try to remove the wrong assumptions of the PM about RSS so that (the) ban on (the) RSS is lifted and RSS members are released from jails… and … are able to contribute to the progress… under the leadership of the PM.’

Around this time, many jailed RSS workers gave unconditional undertakings to get out of prison, signing standard forms the government had prepared that they would not do anything ‘detrimental to internal security and public peace’. Though Bhave did not respond immediately, he was to play a major role in softening Indira Gandhi’s stance towards the RSS.

Chamunda temple and Sanjay’s death

On 13 December, 1980, a helicopter carrying Indira Gandhi landed at Yol Camp in Kangra. The chief minister of Himachal Pradesh, Ram Lal, was there with his ministerial entourage to receive the prime minister.

Indira had arrived to pray at the temple of Chamunda Devi in Palampur, considered an incarnation of Goddess Durga. Interestingly, Indira herself had been hailed as ‘Durga’ nine years earlier, after the liberation of Bangladesh.

The sixteenth-century temple drew thousands of devotees every year. Indira Gandhi was a great believer in the goddess. Until she died in 1984, prayers were offered regularly in her name at the temple, and prasad would be taken back to her in Delhi. ‘She would put money in a lifafa (envelope) and give it to me,’ Anil Bali recounted.

‘Every two months, I would take Rs 101 from her for the temple.’ This time, though, she was on a somber mission. She had arrived to offer prayers in the memory of Sanjay who had died in an air crash on 23 June that year. He had been flying a small plane, a Pitts S2-A, and lost control of the aircraft. Indira had been slated to come to Chamunda with him a day before he died.

When she won in January 1980, Anil Bali had suggested to her that she should personally visit Chamunda Devi after taking the oath of office, and get the goddess’s blessings. The day she took the oath on 14 January, 1980, she had organized a kirtan at her residence at 12, Willingdon Crescent. She had rushed back home to take part in it, soon after the swearing-in ceremony at Rashtrapati Bhavan.

‘Madam, you have to go to Chamunda Devi,’ Anil Bali reminded her at the kirtan. ‘Yes,’ she agreed. ‘Give me four to five months.’ In the first week of May 1980, Bali received a letter from R. K. Dhawan. It said the prime minister wanted to visit Chamunda on 22 June (1980). She would land there at 4:45 p.m., Dhawan wrote. He asked Bali to organize her programme. Bali went to Chamunda and made arrangements for a puja to be done by her when she came. This was to be followed by a havan and a langar to feed the local people and worshippers at the temple.

On the evening of 20 June, a message arrived in Chamunda that the prime minister’s programme had been cancelled. The entire government of Himachal Pradesh, including Chief Minister Ram Lal, had been camping there, awaiting her arrival. When the priest heard she was not coming, he reacted sharply. ‘You tell Indira Gandhi, this is Chamunda. Ma will forgive if an ordinary mortal is not able to come. But the Devi (goddess) will not forgive if the ruler shows disrespect. Devi ki avamanana nahin kar sakte (The ruler cannot insult the goddess.)’

‘Panditji,’ Bali tried to pacify him, ‘there must be a good reason why she could not come.’ They went ahead with the kirtan and prayers on the 22nd as planned. On the 23rd morning, the group left town. ‘We had reached the Jwala Mukhi temple, 50 kilometres on, when my secretary came running (to me),’ Bali remembered.

‘Sanjay Gandhi’s plane has crashed,’ he said, ‘and Pakistan radio is broadcasting it.’

Thirty-three-year-old Sanjay had lost control of the aircraft while doing an aerobatic manoeuvre. Sanjay was known for performing dangerous stunts while at the controls of the small aircraft he flew—a reflection of his devil-may-care attitude to life. Maneka, his wife, had gone for a ‘joyride’ the previous evening when he wanted to show her his latest toy. ‘In the plane I screamed and screamed for, I think, two hours,’ she said later.

‘When we came down, I ran home and told my mother-in-law, ‘I have never asked you for anything in my life. I need you now to tell Sanjay not to fly ‘this’ plane again’.’

The news of Sanjay’s death shocked the country. Anil Bali and Kapil Mohan’s family (who had been at the Chamunda temple) rushed back to Delhi. Bali headed straight for Indira Gandhi’s residence. It was 2.30 a.m. when he arrived. Indira sat with the body. She saw him and got up to have a word with him.

‘Does this have something to do with my not going to Chamunda?’ she asked Bali.

‘Madam,’ Bali tried to calm her, ‘this is not the time (to talk about it). I will tell you later.’

At the chautha (fourth day) ceremony, Bali arrived at 1, Akbar Road. Flanking Indira Gandhi were Sunil Dutt and his actor wife, Nargis. But Indira beckoned to Bali and took him aside, ‘Now tell me what happened.’ Bali told her what had happened the day she was expected at the Chamunda temple.

‘I don’t know who cancelled my programme,’ she said thoughtfully. They were to come to Chamunda from Jammu, she said. Sanjay had accompanied her and was to come with her to visit the temple. She had been told that the weather had deteriorated and that it was raining very hard at Chamunda. The helicopter would not be able to land there in the coming hours. So, they decided to return to Delhi a day earlier. A mystified Bali told her that the weather had not been bad in Chamunda. Nor had it been raining. Somebody had decided on her behalf to give Chamunda a miss. Later, Indira confided to Pupul Jayakar that Sanjay’s death was her fault. She had not performed the rituals and prayers she had wanted to.

Several months after Sanjay’s death, Indira Gandhi’s political aide, M. L. Fotedar, phoned Bali.

‘The prime minister wants to see you,’ Fotedar said. ‘Be sure to be there at 7.30 in the morning.’

She had instructed her attendant, Nathu Ram, to let Bali inside the Residence. She had a cap on her head. ‘She had obviously dyed her hair,’ Bali recalled. She came to the point immediately. ‘I want to go to Chamunda,’ she told Bali. She asked him to make the necessary arrangements.

On 13 December, 1980, she went to Chamunda. ‘As she performed the puja, the pandit’s hands shook.’ ‘I am a diehard Hindu….And the way she read the mantras for Purnahooti, and when she went to do her mathathekna (bowing the head) in the sanctum sanctorum, or (when) she was performing the mudras for kali ki puja, she did it to perfection.

‘And she wept. She just wept and wept and wept. I recalled that the pandit had said that she would come (there) weeping.’ ‘You now have 60 crore beti betiyan (sons and daughters),’ the priest said as he tried to comfort her. ‘Aap inko dekhiye.’ And he added, ‘Aaj ke baad rona nahi (You look after them. You are not to cry after today).’

She took the prasad, did a parikrama (round) of the temple, and left. Accompanying her were Home Minister Buta Singh and Himachal Pradesh chief minister Ram Lal. Outside, she planted trees—one of the key elements of Sanjay’s five-point programme during the Emergency.

She had taken with her Jagannath Sharma, who at one time had worked as a mali for her husband, Feroze. She ensured that a ghat was constructed in Chamunda in Sanjay’s name. ‘It cost Rs 80 lakh, which was borne by Congress leader Sukhram, later to become the Union Communications Minister,’ Bali said.

After Sanjay’s death, many had wondered if Indira Gandhi would quit politics. She did not. But his death affected her deeply. In 1977, Sanjay had brought about Indira Gandhi’s downfall. In 1980, it was Sanjay who had helped her stage a comeback. Within thirty-three months of her being dethroned, she was once again enthroned as the prime minister of India. In all the decisions she had taken after her defeat, her younger son had been her crutch, her co-conspirator, her comrade-in-arms.

And now he was gone. In some way, the prayers she had offered to the goddess on that cold December day in 1980 helped her come to terms with Sanjay’s death. Before leaving the temple premises, she said quietly, ‘I have never seen such a beautiful place.’

When Indira Gandhi flew back to Delhi from the Chamunda Devi temple, she headed straight for a function she was scheduled to address.

The event had been organized by Quami Awaz, the sister paper in Urdu of the National Herald. She walked into the venue in her usual brisk way, but there was a look of fragility about her. Before the function ended, she called her older son, Rajiv Gandhi, to the dais and introduced him to the gathering. Those present made a mental note of it.

For, that evening, without saying so openly, Indira Gandhi was launching her new political heir apparent.

(How Prime Ministers Decide is published by Aleph Book Company)

May 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05