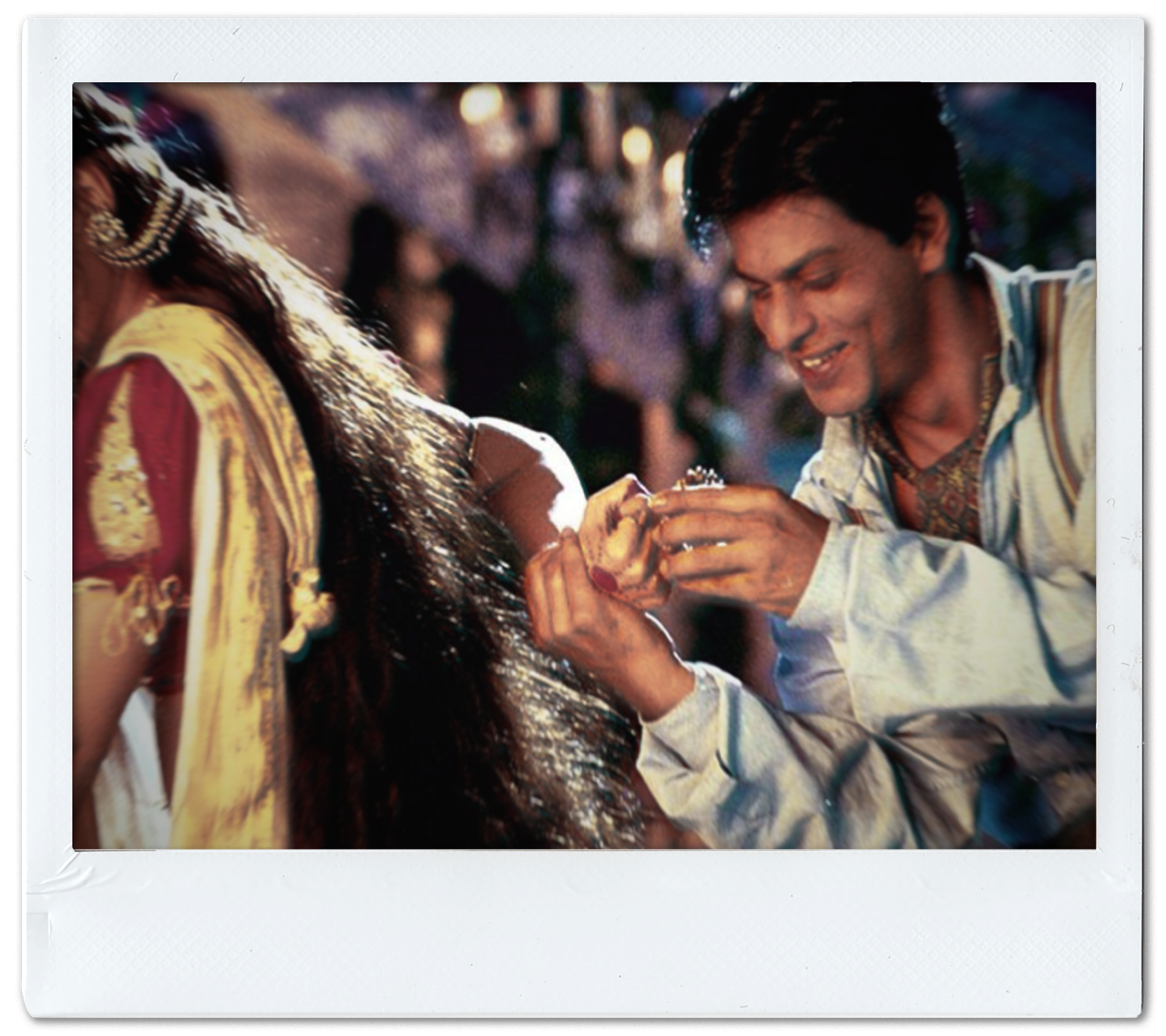

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas is a cinematic interpretation of Sharat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s 1917 Bengali novel. Shah Rukh Khan portrays the titular role, Devdas Mukherjee, who returns from England to his childhood sweetheart, Parvati “Paro” Chakraborty, played by Aishwarya Rai. In the tender song sequence “Bairi Piya”, the teasing lovers read each other’s palms, foreshadowing their true destinies – for Paro to marry an old man, and for Devdas to die unwed.

Cast(e) in Stone: Tensions between Modernity and Tradition

Families intervene when the lovers’ burgeoning desire threatens to become marriage: Devdas’ rejects Paro because of her mother’s dancer lineage, and Paro’s mother responds to the humiliation by arranging her marriage to a richer aristocrat. The gavel finally falls when Devdas’ father catches the lovers. “Our family ranks far higher than theirs”, Sir Narayan Mukherjee commands, “the bird that soars can never have any relationship with fish in the waters.”

The fallout of neighbouring families brings deep-seated tensions to the fore. Any semblance or appearance of modernity is wrested by tradition – the clash of castes emerges most tragically. Father and son, both of whom are ostensibly modern in their outlook, education and dressing, crucially embody the perennial tensions between modernity and tradition. Devdas further personifies Western modernity in his cigarette smoking, his eventual addiction to the Western vice of alcohol, and in his “bohemian attraction to the nether-world of brothels” (Creekmur). Devdas is further alienated from his father and his family when he and Paro’s transgressive love forces the Mukherjees to broach the matter of caste. Ultimately, Devdas is a story where modernity and tradition fail to meet halfway, creating a unique tragedy, especially when taking into consideration the feel-good, modernity-tradition balance found in films released around the same time, such as Kabhi Khushi Khabie Gham… and Kal Ho Naa Ho.

The Sway of the Heart: Song and Dance, Wives and Courtesans

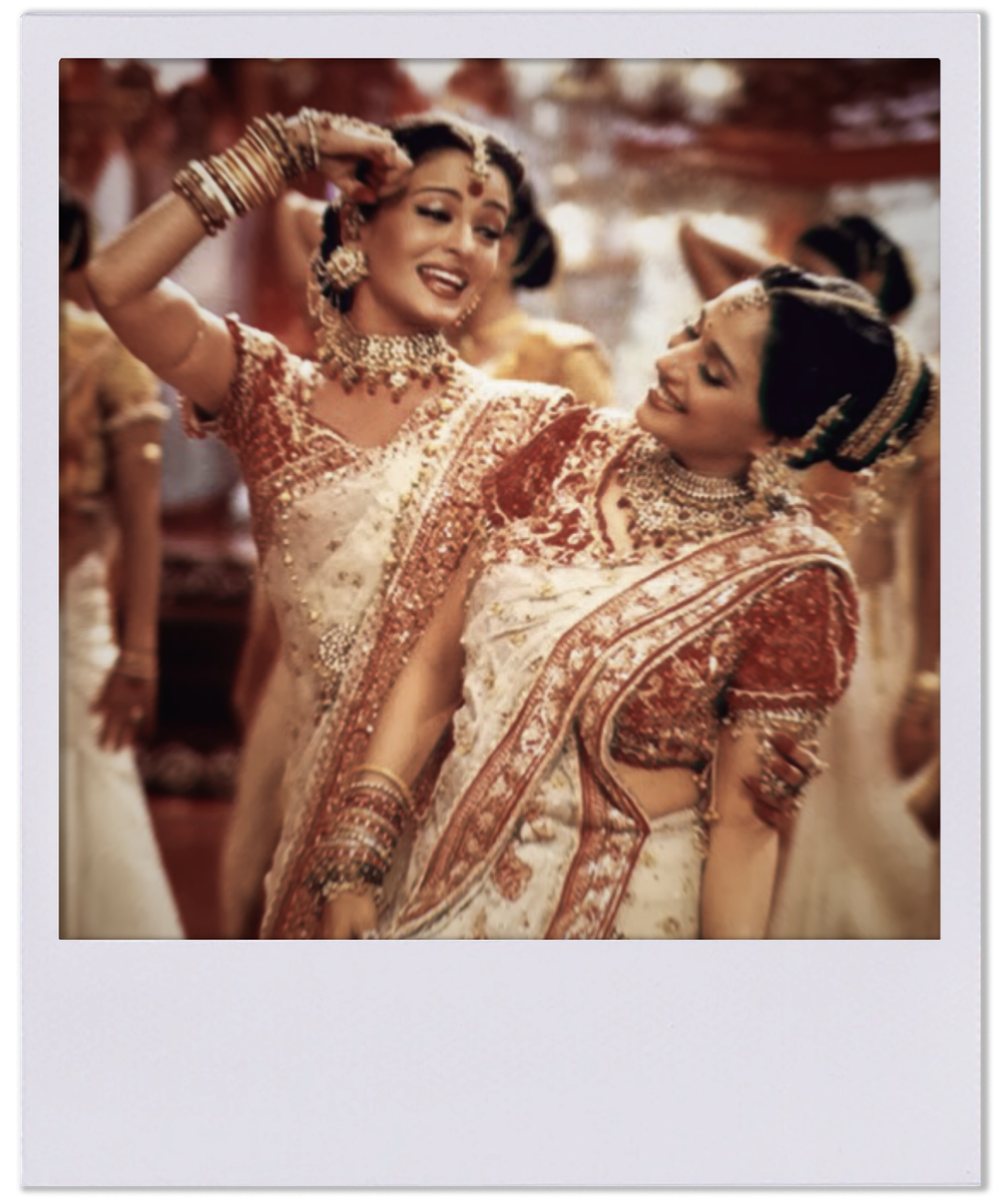

As per conventions of the Bollywood template, Devdas is replete with “ostentatious celebrations of glamour and spectacle”, most assuredly executed through eight elaborate song-and-dance sequences (Bose 1). A forlorn Devdas turns to alcohol as he sets himself on a path of self-destruction, gaining the sympathies of Madhuri Dixit’s Chandramukhi along the way, the good-hearted prostitute who provides solace, as she falls in love with him. “Dola Re Dola” is at the epicentre of this grandeur.

However, “Dola Re Dola” can be argued as a departure from the conventions of the Bollywood template, which often demand a suspension of a viewer’s sense of space and time (Bhattacharjya 69). This can be found within the same film: in “Chalak Chalak”, Devdas, Chandramukhi and the unintentionally destructive Chunnilal suddenly break out into drunken song, dancing as ‘glass collides with another glass’. “Chalak Chalak” is spectacle, no doubt, but bears no significance on Devdas’ narrative.

In contrast, the “spectacular aspects” of “Dola Re Dola” never “override narrative coherence” (Gopalan 412). “Dola Re Dola” fits firmly within the film’s diegetic universe. There is no disruption of the linear narrative – it makes sense to break out into song and dance as Paro and Chandramukhi celebrate Durga Puja. It is a sight to behold: “Dola Re Dola” is the brief coming together of the aristocrat’s wife and the courtesan, of past and present; two women bounded together by their mutual devotion to Devdas, and a bittersweet awareness that they are perpetually trapped in the always almost.

Furthermore, “Dola Re Dola” is a departure from the Bollywood template’s tendency to feature “mindless songs and dances” (Bose 1). In granting the women a platform for “temporary dialogue”, “Dola Re Dola” is more than its opulence and spectacle – it is imbued with meaning as it carries the weight of Paro and Chandramukhi’s “transgressive rapport” (Shresthova 96). This resplendent song-and-dance sequence is thus employed as a cinematic device, playing a pivotal role in driving the plot and pushing forward Devdas’ narrative (Bhattacharjya 52). “Dola Re Dola” sets in motion the course of events: Chandramukhi’s true identity and Paro’s relationship with Devdas is revealed by the conniving Kalibabu, Paro is subsequently forbidden by her much-older husband, Bhuvan, from ever leaving the manor, a decision which ultimately results in Paro’s lamp, lit for Devdas, extinguishing.

Additionally, the transgressive rapport established between both women allows for a deeper discussion about the Indian feminine. This is evident in the following lyrics:

Chandramukhi: You have given me my world. You have given me all your happiness.

Paro: May I never be far from you. Yes, fill the parting of my hair with sindoor.

Chandramukhi: You are the flower of his arms. I am just the dust of his feet.

Chandramukhi’s last line is of particular significance. Chandramukhi casts herself as dichotomous to Paro, her world of disreputable alleys against Paro’s plush manor. Devdas himself emphasizes such a binary when he likens Chandramukhi to a paper flower, and Paro to a lotus, never granting Chandramukhi the right to touch him until he embarks on his final journey to Paro.

However, this apparent dichotomy drawn between Paro and Chandramukhi falls flat upon closer examination. Paro, the woman of the house, belonging to one, and Chandramukhi, the woman of the world, belonging to many – and yet, neither belong to the one they truly desire – Devdas. Furthermore, the aristocrat’s wife and the courtesan are both subject to double standards of patriarchy: Paro’s husband is deeply in love with his deceased first wife, but punishes Paro’s for her devotion to her first love, Devdas; Chandramukhi is stripped of societal recognition and acceptance when, as she astutely points out in her confrontation with Kalibabu, it is in fact ‘the aristocrat who brings cheer to brothels’. Paro and Chandramukhi, for all of their superficial differences, are bounded together in the liminal feminine space of desire without fulfilment, loving but never having.

Conclusion

In examination of Bhansali’s Devdas, the thematic concerns of caste, modernity, tradition, and femininity come to the fore. “Dola Re Dola” is useful in looking at Bollywood song-and-dance sequences as cinematic devices, capable of effectively driving narratives forward.

Works Cited

- Bhattacharya, Nilanjana. “Popular Hindi Song Sequences Set in the Indian Diaspora and Negotiating of Indian Identity.” Asian Music 40.1 (2009): 53-82. Print.

- Bose, Derek. Brand Bollywood: A New Global Entertainment Order. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2006. Print.

- Creekmur, Corey. “The Devdas Phenomenon.” Indian Cinema. The University of Iowa. Retrieved from https://uiowa.edu/indiancinema/devdas.

- Gopalan, Lalitha. “Cinema, Nation and National Identity: Indian Cinema.” Introduction to Film Studies. Ed. Jillian Nelmes. London: Routledge, 2012. 400-425. Print.

- Nandy, Ashis. “Modernity and the sense of loss, or why Bhansali’s Devdas defied experts to become a box office hit.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 12.3 (2011): 445-453. Print.

- Shresthova, Sangita. “Swaying to an Indian Beat… Dola Goes My Diasporic Heart: Exploring Hindi Film Dance.” Dance Research Journal 36.2 (2004): 91-101. Print.