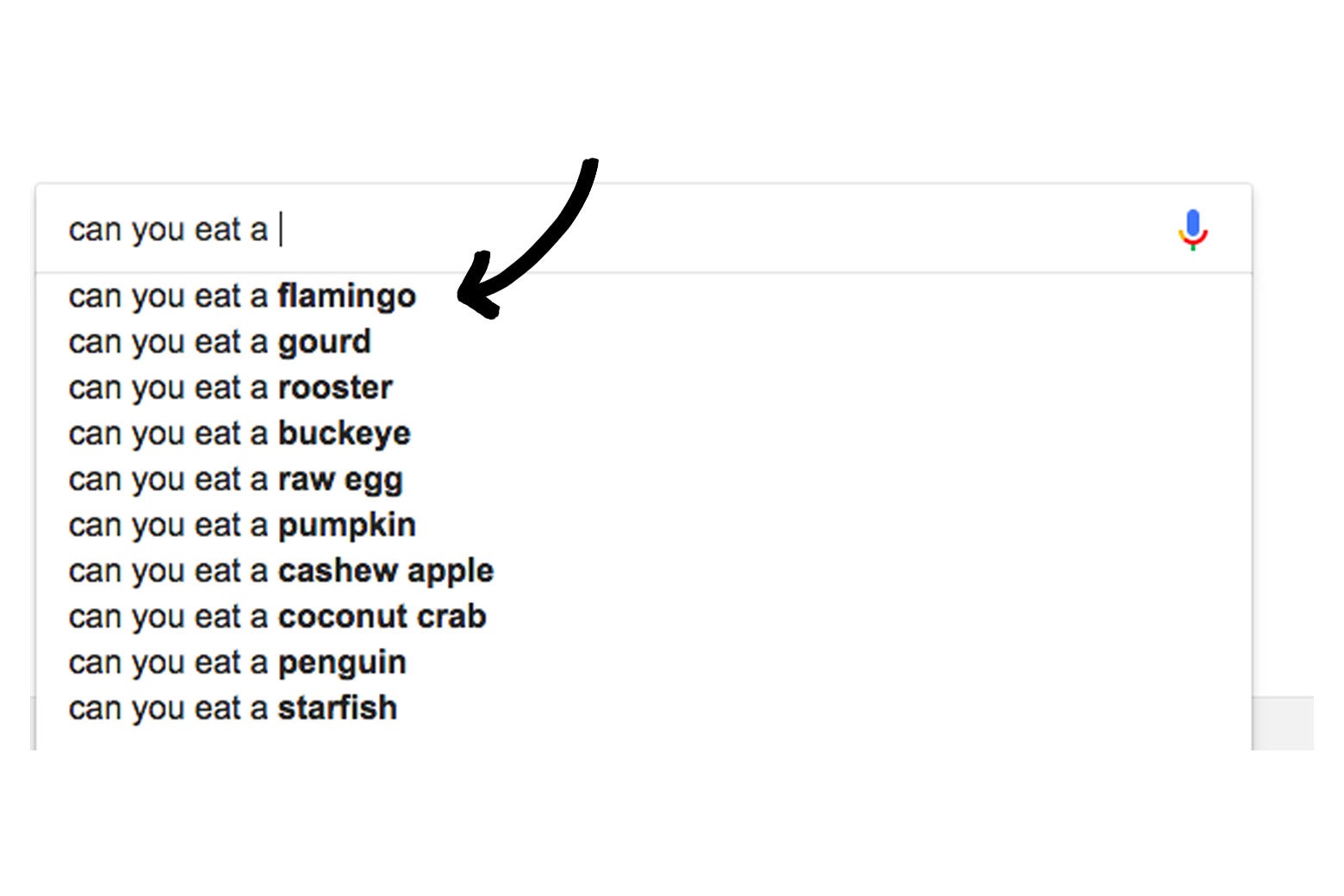

Earlier this month, a colleague discovered, thanks to a tip from a Facebook friend, that if you type “Can you eat a … ” into Google, the search engine offers the helpful suggestion that you complete that query with “flamingo.” At the time of publication, this still holds true across platforms. This got us wondering: Can you eat a flamingo? And why on Earth does Google think so many people would want to know?

To answer the question a fair number of Google users are asking: Yes. Its consumption has been recorded since around the first century, when Romans boiled them with spices and wine. You can eat a flamingo.

But you shouldn’t. In the U.S., as in many other countries, hunting and eating flamingos is illegal. For the most part, migratory birds are protected under federal law, and the American flamingo falls under that protection. Flamingos nest together in large groups, making them particularly vulnerable to hunters, and they do not reach maturity until age 6 or 7, at which point they lay only one egg a year. The birds would not do well in an open hunting season.

We know this because there used to be large populations of flamingos in southern Florida. After hunters in the 19th century began collecting them in large numbers to sell their feathers for ladies’ hats and, as a secondary benefit, their meat for eating, they were essentially wiped out. (In a letter to the Smithsonian Institution, a naturalist writing in the 1860s described going out on a canoe and catching more than 100 flamingos to sell them in Key West for “four or five dollars a pair.”) Most of the American flamingos people see today live in zoos or, more rarely, are natives of Mexico, Cuba, or the Bahamas that flew north or were blown off course in storms.* So to avoid any further human destruction to flamingo populations, you should leave the birds alone.

But we know that in times of desperation, people still do what they need to do: In 2017, the Miami Herald reported that Venezuelans, suffering from a hunger crisis, were ignoring the country’s ban on flamingo hunting and eating other unusual foods, such as anteater. In less dire circumstances, there are reports of flamingos being sold for cheap in markets in some Asian countries—some of which also have laws on the books against killing the birds—and in the Caribbean. (Those who do eat flamingos are also at risk of coming in contact with bacteria that could make them sick, as the animals would not have been inspected or their meat processed in a regulated way. While flamingos aren’t known to have any particular toxins that would make them obviously dangerous, eating any wild animal comes with risks. Cooking meat thoroughly, though, would solve most of those problems.)

What do the birds taste like? Flamingos are filter feeders and subsist largely on algae, crustaceans (notably, brine shrimp), insects, and small fish. According to John Gonzalez, an associate professor of muscle biology and meat science at Kansas State University, the algae diet might give some species of flamingo high omega-3 levels, which would make the meat healthier but result in a slight fishy taste. And because flamingos have lean muscles built for flying distances, they’d taste more gamey—more like duck than chicken.

Ancient Romans, the first on record as having dined on the birds, ate both the body and the tongue. Apicius, a famous Roman cookbook that dates back to the first few centuries A.D., lists a flamingo recipe in which its meat would be boiled with dill, vinegar, leek, coriander and a fruit syrup and served with a sauce made from vinegar, boiled wine, cooking liquor, starch, pepper, cumin, coriander, asafoetida, mint, rue, and dates. “The same recipe can be used for parrot,” the entry concluded. According to Roman food historian Sally Grainger, the ingredients indicate it was a fairly middle-class recipe, and it could have been served covered with the flamingo’s feathers. The tongue, described as having a “specially fine flavor,” was served separately and considered the height of luxury. One account of an emperor notorious for throwing visually extravagant but nutritionally dubious dinners depicts an enormous frittata with pheasant and peacock brains, eels’ eggs, pikes’ livers, and flamingo tongues, all cooked in what was probably a special-made vessel. In the early 19th century, a soldier in the Seminole Wars wrote in letters from Florida about shooting a flamingo—“a large male in perfect plumage, whose brilliant hues my eyes dwelt upon in an ecstasy of delight and admiration”—because he had read in school that Romans ate their tongues. He had the tongue boiled, and at dinner he and his crew “found it perfectly tender and of delicate flavor, but so exceedingly oily and rich that but little could be taken of a morceau otherwise so surprisingly dainty.”

For some more modern theories on how to cook the bird, we polled our more culinarily inclined colleagues and received suggestions for braising, poaching, or frying the meat (and roasting the tongue). A 2009 edition of the gastronomic encyclopedia Larousse Gastronomique suggests you can prepare any bird’s tongue by soaking it, trimming its fat, boiling it, skinning it, and salting it. Brian Bosch, a sous chef at the Continental Midtown in Philadelphia and the brother of a Slate editor, polled some of his fellow chefs and concluded that there are a few options, but none would give the diner a substantive meal worth the effort. One possibility: Because flamingos have such thin wings and legs, you could ignore them and focus only on the tenderloin cut—which, even then, would be so scant that you’d only get a few ounces of meat—and cook it like a tiny steak.

As for the other original question: Why do so many people seem to want to know? According to Google, its SEO predictions are based on “look[ing] at the real searches that happen on Google and show[ing] common and trending ones relevant to the characters that are entered and also related to your location and previous searches.” That doesn’t tell us much, but the search engine’s analytics indicate that while “flamingo” isn’t actually always the most popular search for that line of questioning (“rooster,” “gourd,” and “buckeye” have all given it some competition), it has spiked in certain periods (in October 2018, and apparently, January 2019).

There aren’t a huge number of people wanting to know if a flamingo is edible—the search term sees fewer than 10,000 searches a month on average—but enough to raise the question of why people suddenly become interested. The spikes don’t appear to be seasonal (unlike “gourd”) or pegged to news, so it’s hard to say why, exactly, people got so interested in the question in the fall of 2018. As for why it remains one of the top answers in general, we can also only guess. Maybe visitors to the zoo are so struck by the birds’ flamboyance that they wonder if the birds are exempt from the normal rules of nature. Maybe their presence in many children’s books makes them a point of focus to a more naturally curious demographic. Or maybe, as one source jokingly speculated, Florida is just full of doomsday preppers.

The Explainer thanks Steven Whitfield at Zoo Miami.

Update, Jan. 15, 2019: This post has been updated to clarify that flamingos seen in the wild in Florida have flown north from Mexico, Cuba, or the Bahamas and were not bred in captivity.