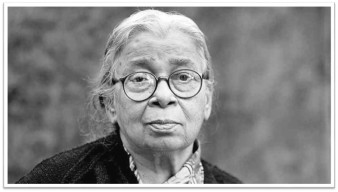

Mahasweta Devi, 1926-2016

One of the ironies of a journalist’s life is unexpected settings for interviews. Whereas I recorded an interview with the German writer and Nobel laureate against the backdrop of a crumbling 19th century mansion in north Kolkata, this interview with the remarkable Bengali writer and activist Mahasweta Devi (b.1926) took place at her hotel suite at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Indian literature and writers were being honoured in 2006 and Mahasweta Devi was at the centre of the celebrations. Although I had read some of her work in translation, and was acquainted with the essential facts of her exceptional life, I did not know what kind of person to expect.

Sitting on a dining chair in the living room was a small, bespectacled woman in a crumpled sari. It was the end of what had obviously been a long and weary day. But her voice was clear and strong; and once the interview began all traces of fatigue vanished. It became vigorous and expressive as she spoke about her life and work with candour, precise recall and emphatic opinion. There were moments—as when she recited the folk lyric about the Rani of Jhansi—when it resonated and filled the large room.

Mahasweta Devi was born in Dhaka into a family with strong intellectual roots. Her father, Manish Ghatak, older brother of filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, was a well-known poet and novelist; her mother, Dharitri Devi, was a writer and a social worker and sister of Sachin Chaudhury, founder-editor of The Economic and Political Weekly, and the sculptor Sankho Chaudhury. She took a degree in English literature from Santiniketan and knew Tagore; much later, after marriage and motherhood in the 1960s, she went on to complete her M.A. and taught English at a small college in Kolkata. By then her short-lived, turbulent first marriage to playwright-actor Bijon Bhattacharya had ended.

Mahasweta Devi broke from domestic confines to start travelling into the hinterland and produced her first book Jhansir Rani (1956), a retelling of rebellion of Rani Laxmi Bai through oral accounts and regional folklore. Her journeys to the poorest tribal districts of present-day Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh became a leitmotif of her life and vast output: she has produced more than a hundred books of fiction, non-fiction and collections of her fiery, crusading and relentless journalism.

Many of her real or fictionalized accounts of marginal lives—the landless, dispossessed, uprooted or grief-torn—are widely available in translation. Among the best-known include Hazaar Churashi Ki Ma (No. 1084’s Mother, 1975), Aranyer Adhikar (The Occupation of the Forest, 1977), Agnigarbha (Womb of Fire, 1978), Choti Munda Evam Tar Tir (Choti Munda and His Arrow, 1980) and Bitter Soil: Four Stories (1998). Her prodigious writing and activism has transformed the narrative of her life into a seamless whole; she has been honoured with the Magsaysay and Jnanpith awards and was given the Padma Vibhushan in 2006.

Asked once what her leisure reading included, she admitted to a weakness for thrillers by John Grisham and Dick Francis, adding, “Dick Francis can’t make the horses talk but he does invest them with some kind of character”.

It must be a good moment for you with several of your works being presented in German translation and a whole seminar built round your huge body of work. What does it feel like?

Unthinkable.

Why unthinkable?

I wrote because that was the only thing I could do. I couldn’t do anything else—cultivate the soil or break stones or other things. Also, writing meant earning, so I am writing and surviving till date. Book fairs and seminars don’t touch me anymore. I have come here and I am mighty proud because my government has sent me, and it is very good to meet people, to touch their hearts and to talk to them. Yesterday when I spoke I said that the right to dream is anyone’s first fundamental right. We must be allowed to dream. People must have the liberty to dream. As long as we can dream, we will go ahead.

You come from a family steeped in the reading habit. Your mother made you read Chekhov and Dickens and Tolstoy. How big an influence was that early immersion in books?

We grew up with books; from childhood on all I have seen is books. Purchasing books and keeping them, maintaining a library. My mother was a great reader as was my father. My maternal grandmother was also a voracious reader. From my childhood, she would give me many books to read, all serious books.

Other influences were your first husband, playwright Bijon Bhattacharya, who was deeply involved in the Indian People’s Theatre Association, IPTA, and your father’s younger brother, the noted Bengali filmmaker Ritwick Ghatak. So reading, writing, making films were a family tradition…

My first husband was both a great actor and playwright; he was one of the founder members of IPTA. From his famous play a fantastic film was made by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas called Dharti Ke Lal. Many families were like that. I repeat, that in our time, our view of the world, whatever we knew about the world outside Bengal, was only through books. Also in my childhood, I was in Santiniketan when Tagore was alive. I saw him very closely. In those days Santiniketan was a very different kind of institution. We were encouraged to read books, use the library, study them and write about what we thought of them. It was something in the air of the country.

What were your earliest writings?

When I was a student of class eight, there was a famous children’s journal and the editor asked me to write a piece on Tagore. That was the first my published writing. But after that I did not pursue writing. Time passed, I got married and later I worked in a garments office. Slowly I started writing for weekly papers. It was great to get ten rupees or fifty rupees for a piece of writing in those days.

A turning point in your life when you started travelling, of journeys to places like Palamau, now in Jharkhand…

Palamau came later. My first book was Jhansir Rani, the biography of the Rani of Jhansi. I read all the available historical material but then I had this intense desire to go and see those places. I knew nothing about Jhansi, Bundelkhand and Gwalior. I just borrowed money from relatives, got into a train, left behind a small baby with his father and went to Jhansi. From that moment my second interest, of collecting oral traditions, became vital for me. I honour and cherish our oral tradition greatly. I will never forget sitting by a fire in Jhansi under the December sky. It was very cold. These Bundelkhandi people were singing, “Patthar mitti se fauj banayi, Kaath se Katwar, Pahad uthakar goley banaye, chalo Gwalior” (From stones and earth she created an army/And from wood she fashion a sword. She turned mountains into cannonballs/ And lead with cry, “Onwards to Gwalior.”) From then on, the Rani of Jhansi became a real woman for me.

Despite your rigorous chronicling of the oral tradition you also speak of your method of research as being forensic—that you are obsessed by statistics, gazetteers and collecting facts…

Yes. But I am also someone who always comes back to history. To me history means the blank space between two printed lines. Therein is the true history of the people. This song about the Rani of Jhansi is an example of that space because the words “Patthar mitti se fauj banayi…” would never appear in history books. So whatever I have learnt in my life is from the people. I have gone to them, I respect them, and I return to them.

You know the name of Draupadi from the Mahabharata, she had five husbands. Fine, Draupadi’s story is well-known and I have written a story about her. But in the 1980s I went to the Himalayas and there I came across Gujjar tribes of cattle-grazers. One woman would marry two, three or four brothers. I asked them why? And they said, in our community, every woman has a Draupadi gotra (lineage). One woman marries three or four brothers. Officially this woman remains the wife of the first brother. Other brothers also marry different wives. But in order to write this, to write the story of Draupadi, I had to read the Mahabharata.

The great impetus of your writing came from giving voice to the dispossessed and documenting their lives. Was that what triggered off your trips to tribal districts that later became Jharkhand?

Yes, I went there in the 1960s, and I saw this horrible custom of bonded labour. There was a man who was bonded to a rich farmer. I saw a bullock cart stacked heavy with paddy. The bullock could not pull it and it crashed. So the rich farmer forced the bonded labourer to pull the cart. While attempting to do so, this bonded labourer named Nageshya broke his shoulder. I asked the rich farmer how he could do such a thing. He said to me that his bullock had cost him a lot of money and that if he had to buy another bullock it would cost him 2,000 rupees, but this man here, he is only a bonded labourer. From these experiences emerged the 1980s movement against bonded labour.

Another change occurred in your life in the 1960s. You had a B.A. in English literature from Santiniketan but you decided to do an M.A. and began teaching English in a small college in Kolkata then you became a teacher. Was that a difficult transition?

It was exactly like that. I was a graduate when I got married but I didn’t do my M.A. I did it long after as a private student and taught in a college. I was this person who had read all these things, so it was alright. I could do it—it was not difficult—but it wasn’t a distinguished career. I had no desire ever to become a distinguished teacher.

Teaching and travelling ceaselessly to tribal districts, to record and collect stories, and also become actively engaged in their struggles—did all this take a toll on your personal life?

My engagement with tribals started with travels to Palamau. I worked extensively there, then Singhbhum and Hazaribagh, which led to my involvement in the movement for Jharkhand. I remain very connected to the forest movements of the tribals; anywhere you go to in India, to the tribal people, mention my name and they will know me.

I wanted to do it. I had set myself free and I did not want to listen to anyone. I did what I wanted to do. Of course, I had left my husband and my son who was quite young. Leaving him was very heartbreaking. I remarried and that marriage also—it lead to nothing. But by that time I had become absolutely absorbed in my work and the people I was working for, the books I was reading and writing.

And you produced not only novel after novel but short stories, prolific journalism and reports.

You may be surprised to know that for the past 35 to 40 years I have been the most indefatigable journalist. I have travelled and walked through the districts, tribal and non-tribal areas, forest areas and hill areas. I came back and wrote for the newspapers. Three columns, say, in a week. Many of them are now being published together because my complete works are coming out in Bengali.

This large corpus of reporting sustained your fiction and also your activism. Do you see any contradiction in these different roles?

No contradiction anywhere. Because I became the voice for a large number of people I would collect data and statistics and bombard the government with my reportage and letters to the authorities.

You also recorded the Naxalite movement in your fiction and non-fiction, the most famous example being your novel Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Ma, later made into a critically acclaimed film, about a mother who rejects her comfortable life after the killing of her younger son…

Movements such as the Naxalite outburst of the 1970s made up a mighty decade. Many of our boys were being killed. I think the reason why Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Ma was an instant success was because of the way, the technique, in which it which it was told—a mother remembering her son’s life. It touched the hearts of many mothers and these killings were happening all over India. But these are things I have to write about and can’t stop. I have two books ready in my mind which I have to put down.

Do you believe that the act of writing—given the range and scale of your work and the readership you enjoy—can bring about social change or the writer and activist go hand in hand to deepen awareness and bring change?

One individual cannot change things but can contribute to a movement in every way possible. Even in my state, West Bengal, there are still two or three persecuted tribes who cause I have espoused. For 20 years I have been publishing a quarterly journal , Bortika (The Lamp), in which tribals contribute stories, not middle class writers.

I used to print questionnaires because I have a vast rural network so that it would reach people in districts. I would ask them important questions like, “Are you a school teacher? Are you an agricultural labourer? Are you a cycle-rickshaw puller? Write your life story”. It is not possible for me to do everything alone. But, I hope, many people in India have been moved to think and to work in this way.

In the end, do you see yourself as a novelist, chronicler or a crusader—or all three?

As a writer. If I write novels, reportage, stories, it is all with the pen. No computers, no e-mails. Only a pen and paper.

October, 2006