In Lucknow, on the banks of the river Gomti, stands not just one statue but a whole collection, and in a breath-taking setting. These statues, each bearing a name, are of freedom fighters, social reformers, and politicians. Some are familiar, others less so. But all are Dalit or Adivasi. The effect is startling, for this, and another similar site in Noida, is India’s only exclusive celebration of the Dalit and Adivasi contribution to the making of the modern nation. This is the Ambedkar Memorial Park, formally known as the Bhimrao Ambedkar Samajik Parivartan Prateek Sthal.

The complex is a feat of monumentalism, spread over a hundred acres in the heart of the capital city of India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh. Made in marble and a sandstone reminiscent of great seats of power – such as Delhi’s South Block or the Red Fort – the park is composed of vast open spaces dotted with bronze fountains, Ashokan columns, urns, friezes and stupa-like edifices. An alley of 124 monumental elephants, evoking the avenues of ram-headed sphinxes in Egypt’s Karnak and Luxor, leads to a massive inclined plane that is flanked by two tall statues of Mayawati, the former Uttar Pradesh chief minister and head of Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), and her mentor Kanshi Ram, both holding sheaves of wheat.

In various cities across the world, statues of figures from the past are being hauled down during protests for racial equality. In Bristol, United Kingdom, a crowd toppled the statue of Edward Colston, a 17th-century merchant who built himself a reputation as a philanthropist on the back of his slave trade fortune. In the United States, various statues of Confederate leaders and explorer Christopher Columbus have been torn down or defaced. In Belgium, several local authorities have voted for the removal of statues of King Leopold II, architect of Belgium’s viciously exploitative colonial enterprise in Congo.

These iconoclastic gestures prompt us to think about the political significance of statues and monuments more generally, including in India. The statues in the Ambedkar Memorial Park raise questions as to whether and why some statues deserve their place in public spaces, and about the politics of their presence, or of the absence of others.

Also read: Dear media, stop Chandrashekhar Azad vs Mayawati tales. Dalits can have more than one leader

Moving the British out of sight

Most regimes seek to outlast themselves by raising monuments as physical traces of their presence and might. They install statues to mark continuity with a glorious past or to honour figures that exemplify that past, and highlight a connection between those who erect them and those they seek to commemorate.

In India, the British peppered the territory with historical figures, not only to commemorate their contributions to the British empire, but to build a visible legacy for that enterprise for generations to come. After Independence, many of these statues were removed or relocated in less conspicuous places. In Delhi, the absurdly large statue of George V placed by Edward Lutyens at India Gate was relocated to the little frequented Coronation Park, alongside more obscure firang dignitaries.

The Congress party in power sought to mark its presence by erecting marching Gandhi in countless localities. Decades later, with the Congress’ dominance long gone, M.K. Gandhi’s ubiquitous presence has become the focus of contestation by rival political parties, which see him as a symbol of the Congress, rather than a symbol of the nation. Could this happen with other national figures too?

Also read: ‘Savarkar Marg’ triggers fresh row at JNU, students paint Ambedkar’s name on signboard

Modelling Ambedkar, his struggles

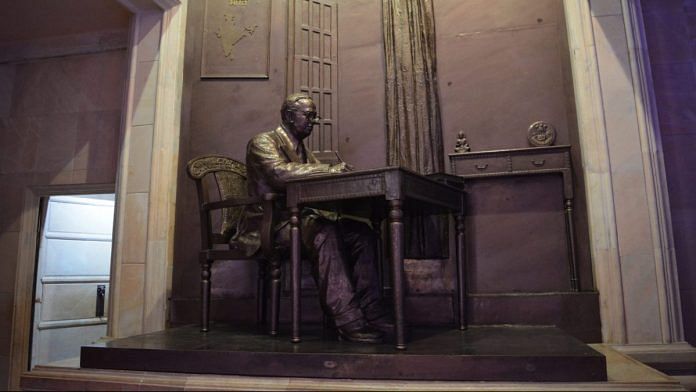

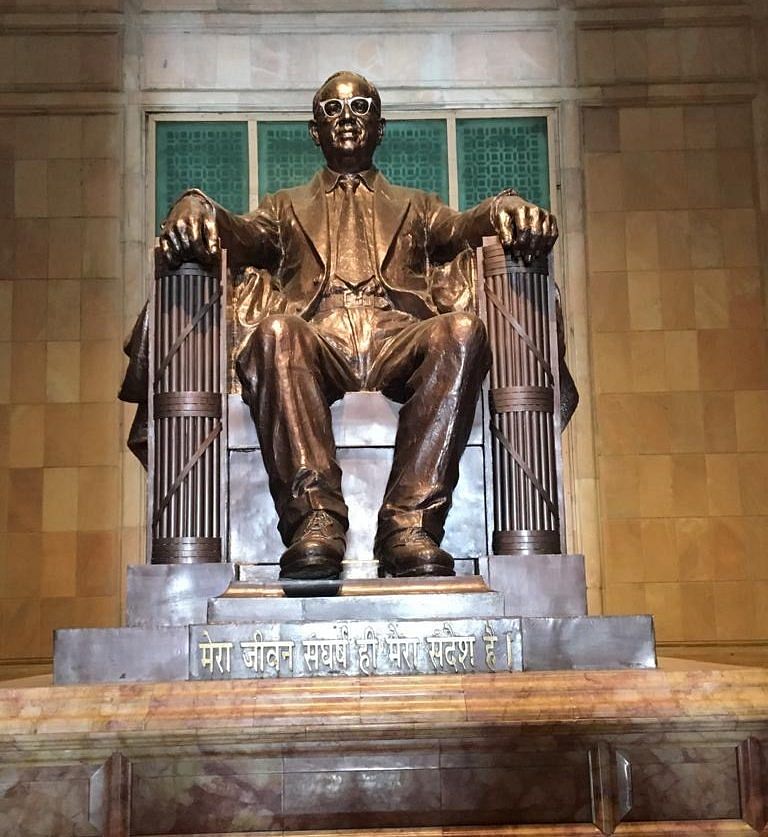

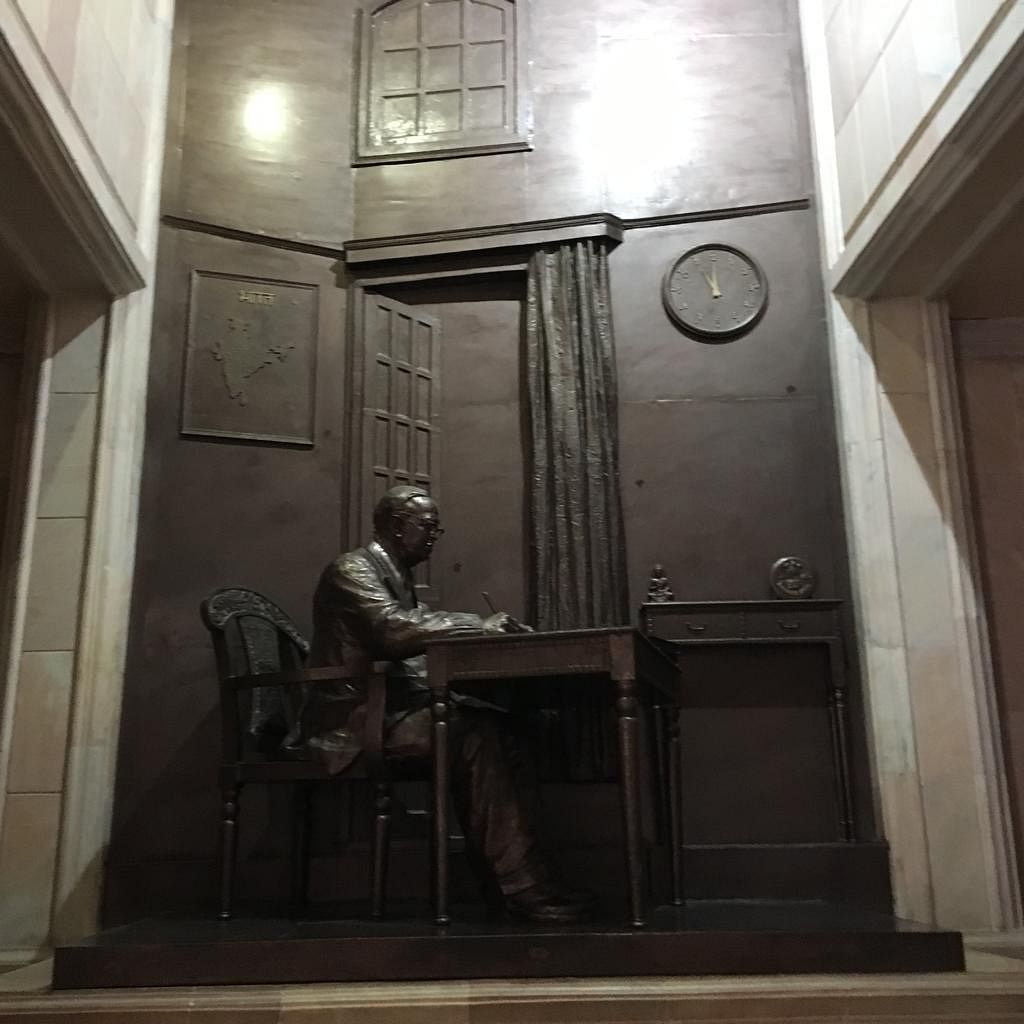

In Lucknow, the centerpiece of the Memorial Park is a 112-foot-high stupa dedicated to Ambedkar. As one enters its cool, dark interior, a vast bronze statue of Ambedkar seated on a throne-like chair, looms out and modelled on the famous statue of Abraham Lincoln in Washington, dominates the space. The message on the statue simply says: ‘My struggle of life is my only message.’

On either side, like the stations of the cross in a cathedral, a sequence of different moments of Ambedkar’s life are cast in bronze. The dominant portrayals of him are as the architect of the Indian Constitution, and of his late conversion to Buddhism as the religion of fraternity.

Ambedkar’s heroic life is connected to the present and to the patron of this vast enterprise, Mayawati, in a composition in which the two stand facing each other. Mayawati saw her own achievement as the first Dalit chief minister of Uttar Pradesh as the rightful culmination of Ambedkar’s struggle for social justice. It was their shared struggle and success that she sought to commemorate through the vast memorial complex.

The location of the Ambedkar Memorial Park in the heart of Lucknow, adjacent to Gomti Nagar, a posh residential colony where mostly upper-caste business, bureaucratic, political and judicial elites reside, was a deliberate statement, a conspicuous and defiant assertion of Dalit presence in the public sphere.

Also read: Political compromises damaged Mayawati’s BSP. Chandrashekhar Azad’s party wants to fill in

Correcting historical injustice

The BSP’s argument for creating these parks and statues was to correct the unjust omission and erasure of Dalits from Indian history and public art. The history carved into stone by previous regimes had always denied space and recognition to this large segment of India’s population, and the scale of the park – monumental – is meant to match both their numbers and the scale of injustices inflicted upon them.

To build it, Mayawati ordered the elevation of what was then a swampy area by several feet, had a 22-foot-deep canal dug, and changed the course of the river by damming its banks to avoid flooding.

This is only one of many similar complexes built by Mayawati over her four tenures as chief minister. The Manyavar Shri Kanshi Ram Ji Smarak Sthal is an 86-acre memorial park with a 177-foot-high Roman Pantheon or US Congress-like structure, two dozen 52-foot-high bronze fountains, and giant marble elephants. There are six other parks on smaller scales in Lucknow alone and another memorial, Rashtriya Dalit Prerna Sthal and Green Garden, in Noida.

While the BSP insists that the building of these parks was an act of corrective justice, it is evident that they also serve a political purpose for both the present and the future. Critics have decried (and legally challenged) the enormous cost paid out of public funds, which they say could have been better spent in improving Dalit lives. But Mayawati and her party respond that a permanent visual inscription of Dalit heroes onto the landscape of India serves to improve the self-esteem of Dalits.

Also read: Bristol brought down slave trader’s statue. This is what India should do with Manu statue

Claiming Ambedkar

It is undeniable that the relatively uncontroversial memorialising of Ambedkar is directly connected to the far more controversial apotheosis of Mayawati herself, their twinning imprinting her presence in the public consciousness. In each iteration, she appears exactly as she has been seen throughout her political career, sporting her signature short hair and a handbag, symbols of her modernity echoing Ambedkar’s suit and tie.

The sheaves of wheat that she and Kanshi Ram bear indicate their earthy origins, firmly locating them in India’s soil, even as their enormous statues aspire to touch the sky. The repeated use of stone elephants as guards of honour to the heroes simultaneously makes them regal and echoes the BSP’s blue elephant election symbol. During the 2012 Uttar Pradesh assembly election, the Election Commission of India ordered that every elephant be wrapped in yellow tarpaulin and every Mayawati statue be concealed under plywood boxes to create a level-playing field during the electoral contest.

However, these memorial parks are also intended to leave a much longer legacy than electoral anecdotes. By placing her statues contiguously with Ambedkar, Kanshi Ram and others, Mayawati assimilated herself into the Dalit pantheon headed by the Buddha, whose religion Dalits have chosen to adopt. Generations of detractors may argue about the wisdom of such expensive subaltern ornamentalism, but for the intended audience, there may be a sense of historic justice being done.

So, not all bronze statues of past heroes need to be symbols of injustice. Sometimes, they are monuments to the enslaved. In the case of the Ambedkar memorial, they might have won greater admiration had they not been linked so obviously to the clay feet of the living.

Mukulika Banerjee is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Director of the LSE South Asia Centre. Gilles Verniers is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Ashoka University and Senior Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research. The views expressed are personal.