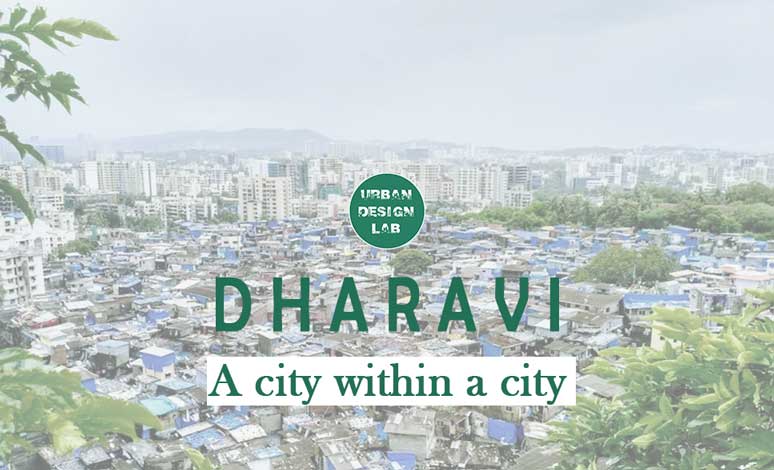

Dharavi – A city within a city

Dharavi is Asia’s largest slum development and is largely regarded as an eyesore in Mumbai’s severe urbanity. Open sewage, packed hutments, small lanes, and poor living conditions are all common images of the setting. Despite these limitations, Dharavi has evolved into a highly dynamic and thriving ecosystem fueled by the diverse cultures and economic sectors that make up society. It has roughly 520 acres of land and is located in the centre of Mumbai, surrounded by different expanding residential and commercial projects. It started off as a fishing town, but when the plague hit India in 1884, the British government moved much of its industry to Dharavi, a peri-urban region of Bombay. Dharavi has grown in population since then, having a population of one million or more now. Leather, recyclable goods, pottery, and other industries have sprung up as a result of the country’s informal economy.

Living in Dharavi

Due to the scarcity of land and skyrocketing real estate prices in Mumbai, many people have sought refuge in the city’s slums. People living in slums endure the burden of daily life in the form of diseases and a lack of basic human requirements. People move to the slums for a variety of reasons, one of which is the scarcity of inexpensive housing in the city’s centre and outskirts. To reduce significant human-centric repercussions, it becomes critical for a city to cater to every income category.

Dharavi’s living circumstances have become a hot issue of criticism on national and international venues. This article will outline two major elements of living in Dharavi’s slums, as well as the initiatives that have been made to rebuild the area.

Housing:

With a population density of about 277,136/km2 (717,780/sq mi), Dharavi is one of the world’s most densely populated places. Residents of Dharavi, like most slum dwellers around the world, live in illegal housing units with few utilities and are socially excluded. The majority of these are 120 sq ft in size and can accommodate four to ten people. People from low socio-economic backgrounds can afford to live here because the rentals are substantially lower than in other parts of the city. A kitchen, storage, and a sleeping section that may also be utilised as a living room are all common features of these homes. Residents have become unbearably burdened by the slums’ cramped informal settlements and fragile constructions, which has been worsened by drastic weather variations and Mumbai’s flooding. The situation has gotten to the point that it’s uninhabitable. Women also have to live in a dangerous atmosphere with minimal privacy.

Sanitation:

The public health in Dharavi has long been a subject of concern. The bulk of slum dwellers rely on public restrooms and toilets, which are frequently dirty. Water is available from public standpipes strewn over the slum. In addition, the few lavatories available are filthy and dangerously broken down. Mahim Creek is a local waterway where locals routinely urinate and defecate, resulting in the spread of infectious diseases. In the slums, there are few wells that produce non-potable water. Due to a scarcity of potable water, residents rely on creeks and wells for washing clothing and drinking water, leading health and hygiene to deteriorate. Increased air pollutants, foul odours, and septic conditions have resulted from an open sewer and no designated garbage disposal zones.

Status of redevelopment:

Despite these circumstances, Dharavi has a lot of promise in terms of location relevance in Mumbai’s urbanscapes. Its land worth is estimated to be $1.3 billion, and it is positioned near Mumbai’s business centres at the junction of two main railways. Underneath its packed layer of matchbox-sized shanty dwellings, Dharavi’s industries generate more than $1 billion in annual revenue.

The Maharastra state administration has acknowledged the need for Dharavi redevelopment and has attempted to draught a proposal on multiple occasions. Disparities between the government and other slum stakeholders, on the other hand, have resulted in a five-decade deadlock.

Water, electricity, latrines, and sewage disposal were all part of the Slum Improvement Programme (SIP) of 1972, which was designed to provide basic facilities to slums. Despite this, due to a lack of a full census of Mumbai’s slums, it was unable to carry out these plans. In 1976, the government attempted to grant “legitimate status” to slum inhabitants. Residents were required to provide picture identification and pay a nominal fee, a portion of which was paid to the government as land rent. This programme permitted residents to renovate some old houses and build lofts on top of existing structures. Electricity and water were also made available. However, due to administrative issues caused by a lack of reliable records on the number of occupants and houses, the scheme was cancelled in 1991.

The World Bank supported the Slum Upgradation Programme (SUP) in 1985. Under this scheme, existing slum land was leased out to cooperative groups of slum dwellers at affordable rates, and loans were made available for environmental and housing improvements. However, because asset distribution to households was unequal, battles over land value persisted, producing unhappiness among particular slum groups who did not profit from the scheme. This programme also failed to overcome a fundamental slum redevelopment roadblock: a large percentage of the slum was located on privately owned land that had been encroached upon, making it difficult to obtain land for slum redevelopment.

In the same year, the Prime Minister Grant Project was launched, with Rs. 30 crores set out for Dharavi reconstruction. Housing societies were granted the option to choose their own architects under this system, while the government engaged construction contractors. The slum’s roads were supposed to be enlarged to make them more accessible to cars. However, the designers failed to account for the slum’s large population density, making it difficult to evacuate residents to allow for development work. In 1995, the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) formed the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) to address the issue of slums in the state through a Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS). Many of the faults in prior systems looked to have been ironed out in this scheme. The SRS provided rewards to every slum dweller who voted in the 1995 election. To lure private developers, the strategy established the notion of Transferable Development Rights (TDR), which would allow developers to transfer a portion of the extra SRS rights to other regions of the city.

The strategy, however, did not work out as planned. Only 3,486 of the estimated 100,000 apartments had been rehabilitated by 2000, despite the fact that it required the permission of three-quarters of the population. Several tenants who were given these rebuilt units just rented them out for extra money while continuing to live in their improvised hovels. The strategy was also criticised for favouring private developers over redevelopment because it allowed for the transfer of freed-up property to private developers despite Dharavi’s already dense population.

In 2004, the government proposed the Dharavi Redevelopment Project, in which developers would rehouse Dharavi people in 300-square-foot apartments with built-in high-rise tower blocks, freeing up land for their own development projects. While the tower buildings alleviate the slum’s existing hygiene and sanitation issues, they have been met with intense criticism from its residents. Residents feel that a tower will disrupt the community spirit that has allowed Dharavi’s micro enterprises to survive for so long, as well as drastically increase the area’s already dangerously high population density.

The most recent urban rehabilitation plan suggested for the Dharavi neighbourhood is led by Mukesh Mehta, an American-trained architect. To accommodate the area’s 57,000 households, the plan asks for the building of 2,800,000 square metres (30,000,000 square feet) of houses, schools, parks, and roads, as well as 3,700,000 square metres (40,000,000 square feet) of residential and commercial space. Existing inhabitants believe the reduced permanent alternate accommodation of 33 square metres (350 square feet) per tenant is insufficient, and there is still substantial local opposition to the plans. In addition, only families who lived in the region before the year 2000 would be relocated. Residents have also expressed concerns that some of their “informal” companies will not be relocated as part of the redevelopment plan. In response to this criticism, the Dharavi Community Land Trust has been established, which will be made up of residents, landowners, and neighbourhood associations.

Future prospect:

With numerous roadblocks in the way, redevelopment of the Dharavi slums is an absolute necessity for the residents living in and around the slums. The strategic location and potential of the slums can benefit a financial and thriving city like Mumbai, which is rapidly expanding in a linear sprawl. However, redevelopment plans should not alter much of the slum’s existing informal economy or businesses, which are affecting locals’ livelihoods. It could cause disruption to the laid fabric and have a negative impact on slum dwellers. Many private companies and real estate developers may be opposed to the idea of slum dwellers legally occupying prime real estate land through the establishment of communal trusts. They might threaten to withdraw their support for local government. Dharavi’s state is depleting dramatically on a regular basis, with a population that outnumbers available land. As previously discussed, the location’s potential, set economy, consideration of existing slum dwellers, and well-planned redevelopment schemes can all contribute to the city’s and residents’ overall growth.

About the Authors

Urvi Basu is an architect from Mumbai who has graduated from Ctes college of architecture, Mumbai University in the year 2020. She has gained experience in designing hospital, hospitality and residential projects from project management and architectutral design firms. As the global community realizes the sparks of an irreversible climate, she wants to be proactive in the processes of improving the built environment with appropriate solutions and innovative processes to provide sensitive designs. Her area of interest lies in learning about integrating design with a futuristic approach to development that can mitigate impacts through conscious urbanism in inter-scalar forms.

Related articles

What Is an Urban Heat Island?

What is urban Health?

Leave a Reply

UDL Photoshop

Masterclass

Decipher the secrets of

Urban Mapping and 3D Visualisation

Session Dates

4th-5th May, 2024

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “