It was a different time, simpler and slower-paced.

Marty Oakland remembers what it was like growing up in West Arlington in the 1940s and ’50s: “There were more cows than people. It was all dairy farms. Route 313 was a dirt road and I used to ride down with my fly rod and baseball glove to the covered bridge,” he said during a 2010 interview.

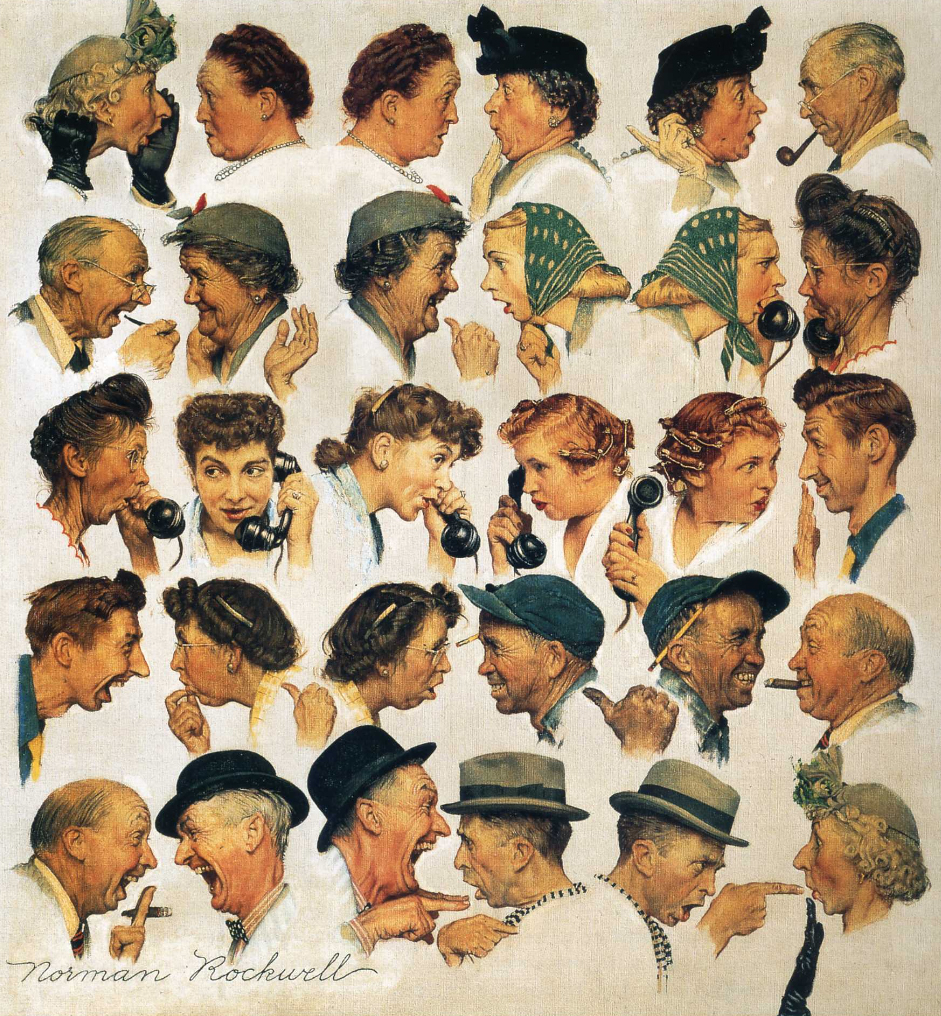

On summer days, Oakland and his friends would swim or fish, or, if there were enough of them, organize a baseball game. The scene was like something out of a Norman Rockwell painting, which it essentially was.

Rockwell, who lived in Arlington for 14 years, including 10 in a house within hailing distance of the covered bridge, was no doubt inspired by the freshness of those summer days, the innocence of those children, and the sense of community in a small Vermont town.

Rockwell’s paintings helped create our image of mid-20th century America. His works, many of which first appeared as covers for the mass-circulation Saturday Evening Post, are alternately poignant or humorous tributes to what he saw as the virtues of American life, including patriotism, hard work, love of family, and neighborliness.

During Rockwell’s Arlington years, the faces of Vermonters were the face of small-town America, as the famed artist enlisted dozens of his neighbors to pose for his paintings. Rockwell insisted that real, ordinary people populate his paintings. “I paint human-looking humans and professional models just don’t qualify,” Rockwell once wrote. The artist immortalized his neighbors as the farmers, soldiers, housewives, Cub Scouts and schoolchildren of America.

Looking for just the right face

The Rockwells — Norman, Mary, and their three sons — arrived in Arlington in 1939, lured by the arts community that had taken root there. Transplants included poet Robert Frost, writer Dorothy Canfield Fisher, painter Rockwell Kent, and many others.

Though the Rockwells had connections with the outside world that most Vermonters did not, they didn’t stand aloof from the community. They joined the Grange soon after arriving and were regular fixtures at square dances, where Norman often stood at the door, taking tickets, and then stayed afterwards to sweep the floor.

He kept his eyes open for models at those dances and meetings, and simply when passing through town. Rockwell was always looking for just the right face to bring his newest idea to life.

“Some artists feel they can create the type they want from anyone but I believe this is all wrong,” he said. “When you have a good idea clearly in mind(,) spare no effort to get the ideal character for it.”

He typically paid his models $5 for posing, a fair wage in rural Vermont at the time. He might have gotten them to pose for free, but Rockwell was a stickler for details.

“The very fact that you are paying them is likely to cause them to give their best,” he explained, “and if you pay them, you are justified in demanding it.”

Rockwell’s family originally lived in a house in town, but fire destroyed his nearby studio in 1943. The fire also claimed many of Rockwell’s paintings, along with the props and costumes he had accumulated over the years. The blaze prompted the family’s move to the house by the bridge in West Arlington. Rockwell arranged to have a new studio built beside the home.

‘Both my money and my pride’

If Vermonters often worked as his models, they also served as some of his trusted critics. The artist would sometimes invite his new neighbors, dairy farmers Jim and Clara Edgerton, over to look at a work in progress. “He valued their opinions, and they felt comfortable enough with Norman to volunteer their true thoughts,” recalls their son, James “Buddy” Edgerton, who published a memoir of that period, “The Unknown Rockwell: A Portrait of Two American Families.”

Though Rockwell was a famous artist and the Edgertons ordinary farmers, the families developed a strong friendship.

Rockwell hired 13-year-old Buddy to do odd jobs at the work site and paid him almost as well as the men. “It gave me just what I needed in pocket money to be able to do things with the Rockwell boys — go to the movies, get ice cream and cold sodas, or buy baseball cards,” Edgerton writes. “…Norman — being Norman — had figured a way to let me have both my money and my pride, so that I could do things with his boys who were not poor like us.”

The new studio featured a large, two-story-tall main room with a fireplace and big windows that let in enough light for Rockwell to paint by. In the back were a kitchen and darkroom. The second floor contained storage for Rockwell’s art supplies, costumes and props.

By the time Rockwell moved to Arlington, he relied heavily on photographs to help create his images. Rockwell initially had qualms about using a camera, feeling it was cheating. “Are you going to be an artist or a photographer?” he remembered asking himself.

Some of Rockwell’s fellow artists, including Edward Hopper, criticized him for the practice as well. But Rockwell later said he realized that artists through the ages have used available techniques — “the camera obscura, the camera lucida, mirrors et cetera” — to help their drawing.

He often improvised with objects in his studio to create his photographic studies, using a table to stand in for a lunch counter, or a chair to act as a car seat.

Once Rockwell saw the advantages of using photographs to capture ideas, he never turned back. He realized that photography had definite advantages. In his work, he was always trying to capture a precise moment and his models found it hard to hold a natural expression. “As the hours passed, the expression would sag or freeze into a grisly parody of glee,” Rockwell wrote.

Edgerton’s sister, Ardis Edgerton Clark, said Rockwell had another reason for relying on a camera: “He couldn’t really afford to take a lot of time with the Arlington models because they were all working people.”

Picky about models

Rockwell was fortunate that his fellow illustrator Gene Pelham, who also created works for the Saturday Evening Post, had likewise settled in Arlington. Pelham was a skilled photographer and helped Rockwell capture his ideas.

Rockwell was picky about his models. He would sometimes have Pelham photograph several before selecting the one who best fit his vision of a painting. And with each model, he would have Pelham take numerous photos for Rockwell to use in his composition. Rockwell once quipped that “if you’re going to sin, you might as well sin completely.”

Once he had his model costumed and props ready, Rockwell would act out precisely what he wanted the model to do. Some reference photos show Rockwell prompting his models from the edge of the image.

You can see many of these reference photos by visiting the digital collections of the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where Rockwell lived and worked for the last 25 years of his life. The Rockwell museum houses the largest collection of the artist’s paintings and drawings, nearly 1,000 pieces in all.

Though Rockwell usually worked with models in his studio during his Arlington years, he sometimes arranged to shoot photos on site, as he did for his painting “Homecoming Marine.” Rockwell arranged with Bob Benedict to use his service station in town for the setting. Edgerton writes that Benedict and his brothers spent days cleaning the place, much to Rockwell’s chagrin. The garage looked too neat; it no longer looked real. But he kept his disappointment to himself.

Before posing his models, Rockwell subtly asked to have a few tools scattered here and some rags tossed there. Slowly, he undid some of the brothers’ tidying. “(I)n Norman’s quiet way, without hurting the Benedict brothers’ feelings, Norman made sure that the real life of the garage was captured for the Post cover,” Edgerton writes.

In the painting, a Marine just returned from the war sits holding a captured Japanese flag while talking to a group of men and boys, who listen with rapt attention. Among those who Rockwell got to pose for the piece were Benedict, dressed in his mechanic’s clothing, and Nip Noyes, Arlington’s town clerk and newspaper editor.

How a painting is built

The Rockwell Museum’s digital collections lets you glimpse the artist’s process. A search for “Homecoming Marine” turns up nearly three dozen reference photos, as well as images of Rockwell’s carefully rendered drawing of the scene on canvas before he started painting and the finished piece as it appeared on the magazine cover.

Because the composition features seven figures, Rockwell had models pose in different combinations, sometimes in pairs or alone. Noyes poses alone, sitting on a box. In one photo he is wearing a suit with a fedora perched on his head. In another shot, he’s dressed as a police officer. Rockwell went with the policeman in the painting.

The focal point of the painting is the Marine. Rockwell had a series of photos taken of him sitting next to a young boy, Rockwell’s son Peter. The poses differ only very slightly; the artist seems to have been trying to find just the right relationship between the two figures.

To pose as the returning Marine, Rockwell enlisted the help of 19-year-old Duane Parks of Dorset. Parks was himself a private in the Marines at the time, though he had not yet shipped out. Rockwell spotted him at a square dance in Arlington that Parks attended in 1943 while on leave from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Parks initially rebuffed Rockwell’s request, but his family talked him into posing. In the reference photographs, he is holding a captured Japanese flag. Life imitated art: Parks ended up seeing action in the Pacific for the last two years of the war before returning home.

The resulting painting is a quintessential image of World War II-era America. The image appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post on Oct. 13, 1945, two months after Japan surrendered.

Not incidentally, the piece sold at auction in 2006 for $9.2 million. The images of America that Rockwell created in Vermont still have a powerful allure.

Rockwell notes:

The Norman Rockwell Museum is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day except Wednesday, when it is closed.

The museum is looking for assistance in updating its database. If you search the database and recognize people in reference photos who are unidentified, please email the museum’s archivist, KL Pereira, at kpereira@nrm.org, so their names can be included.

Among the ways visitors can explore the digital collections is by searching the title of the painting; or in the case of reference photos, search by keyword for the name of the models. Clicking on the thumbnail images will open larger versions. Clicking on the title next to the thumbnails will bring up information about the photograph, including any known names of people appearing in it.

More information about Rockwell’s use of photography can be found in the 2009 book “Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera,” by Ron Schick.