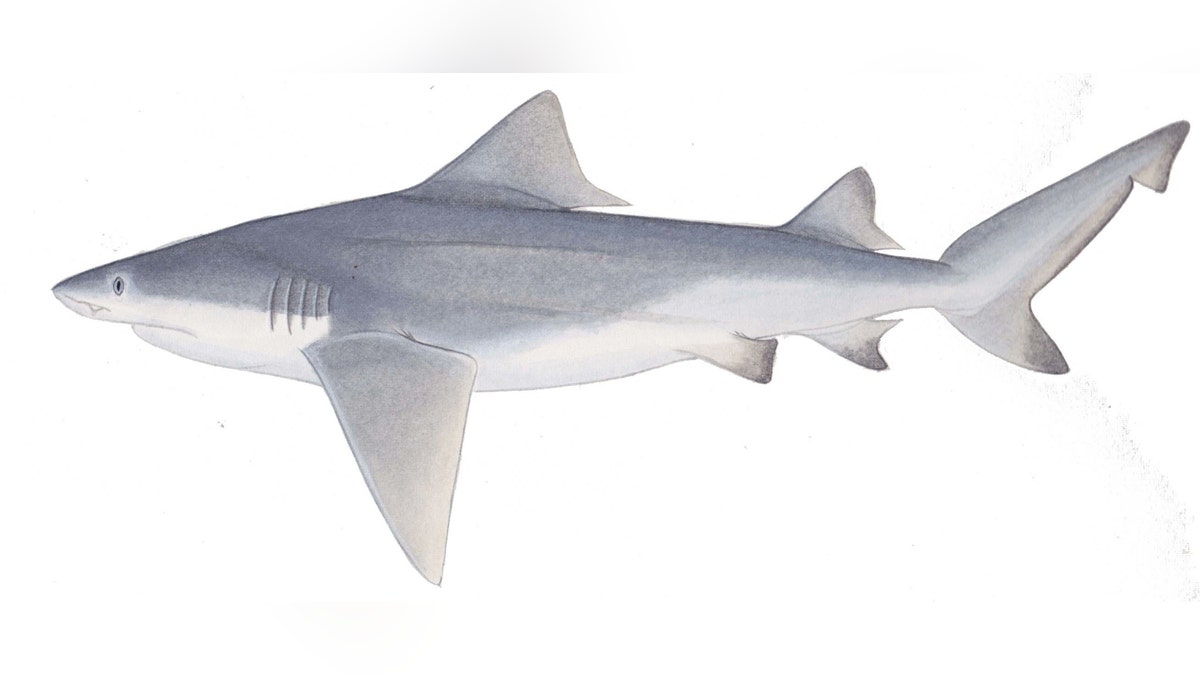

This is an image of the shark Glyphis glyphis which is found in rivers of Asia. (Lindsay Marshall)

For decades, stories persisted of a shark that navigated rivers of Asia and the South Pacific, sometimes taking a chunk out of the unsuspecting bathers or those washing their clothes.

But few people had actually seen one of these critically endangered predators.

Now, an international team of researchers is shedding a little more light on this family of sharks known as Glyphis. Using DNA sequencing, the researchers in a study published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concluded that three different species was actually just one, Glyphis gangeticus. The range of this shark is believed to go from the rivers from India – hence its name - all the way to Malaysia.

In a separate paper published in PLOS One earlier this month, many of the same researchers also rediscovered two species of the shark - Glyphis garricki and G. glyphis - in the rivers of Papua New Guinea for the first time since the 1970s. Again using DNA sequencing, they determined they were the same species found in Northern Australia.

Related: Study finds more sharks than ever swimming in waters along the East Coast

“The river sharks are particularly mysterious,” Gavin Naylor, a professor at College of Charleston and the Medical University of South Carolina who was a co-author on both papers, told FoxNews.com.

“They are archetypal, typical looking sharks like a grey reef or bull shark. They sort of look like that but they have got tiny little eyes and very broad fins,” he said. “These are adaptions for living in very turbid water. If you have a look where these things live, the visibility is about an inch. It’s completely muddy water.“

First discovered back in 1839, Naylor said little is known about this group of sharks simply because so few live sharks have ever been caught. That has helped fuel their outsized reputation as one of the top predators of river systems.

“Many people have never seen these animals,” Naylor said, noting that many have been identified from various body parts that have turned up in markets or that are in museums.

“They have got this apocryphal mysterious kind of reputation. They were believed – at least one species, the Ganges River shark – was believed to occasionally bite bathers in the Ganges River. But nobody ever saw them. It was a mysterious, frightening thing that some sort of monster grabs you but nobody knows what it is.”

The fact that so little is known has helped breed plenty of misinformation about the shark – beyond its menacing reputation.

Until Naylor and his colleagues started looking into shark, there were believed to be three species across Southeast Asia – the Ganges River species as well as Glyphis fowlerae from Malaysia and Glyphis siamensis from Myanmar. But thanks to the recent DNA work, all three turned out to be the same species.

In the Western Province of Papua New Guinea, William White, of Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, set out to examine shark and ray fisheries. As part of the four-year project, he was able to work with local fishermen in a place called Daru to discover the two species of river sharks that also call Australia home.

Related: Rare ‘sofa shark’ stuns scientists

“They found that the jaws and fins of a large, G. glyphis were brought for sale by a local fishermen. He also had different fins of what looked to be the northern river shark Glyphis garricki,” Naylor said. “Will had the good sense to get some tissue samples to see if it was the same as the ones we had from Northern Australia. We sequenced them and indeed they were.”

Naylor said the rediscovery of the sharks is good news – sort of.

“It gives you hope but you are not sure if they have always been there and we just discovered them because the fishing pressure has increased or we have discovered them because they are making a comeback,” he said. “It’s hard to tell.”

White agreed but admitted the discoveries illustrate just how little is known about what lives in the rivers of a remote, mountainous place like Papua New Guinea.

“In the context of the river sharks, more work is needed to determine what if any affect pollution and habitat degradation from processes such as mining are having on their populations,” White, also a senior curator at the Australian National Fish Collection, told FoxNews.com, via email. “We barely have the baseline data for some species such as river sharks to measuring the effect of threats such as mining is not possible at this stage. However, it needs to be a major consideration when discussing future management decisions that need to be made. It is possible that PNG still holds a relatively good population of river sharks compared to many other locations in the world.”

Together, Naylor and White said the findings are helping answer some of the questions about the sharks and could help with conservation, since we know the Ganges River shark range was much more widespread and most likely includes both salt and freshwater environments.

Related: Pro surfer fights off shark in incredible encounter

“If you have got lots of different species and each species is supposed to occur in a distinctly different habitat, then you have to be very careful about preserving each of those species,” Naylor said. “If you find out that, in fact, it’s one species that is distributed over a wider area, then there is not quite so much pressure to conserve every single one of those different populations when they are all the same thing. It also tells us this very same species is adaptable to living in different environments. It can live in Pakistan. It can live in Borneo and it can live in Myanmar.”

But he and White acknowledged there is still plenty to learn about this elusive shark, including how they navigate the muddy river waters and “make a living there”, how many young they have and the mechanism they use to transition from salt to freshwater and back.

And with the recent discoveries in Papua New Guinea, it begs the question over whether there might be even more of these sharks out there to be found.

“DNA sequence data derived from jaws collected in Bangladesh is distinctly different from anything described to date. But we don’t have a specimen,” he said. “It’s completely different than any of the others. So, there is a species out there that we don’t know about.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated from an

earlier version to clarify information on shark DNA sequence data.