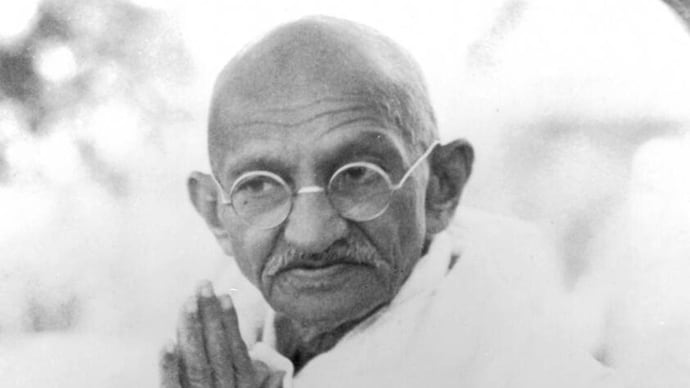

The other side of the Mahatma Gandhi story

Gandhi remains a living figure for his critics as generation after generation discovers yet another of his ‘failings’

(NOTE: This is a reprint of an article that was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated October 7, 2019)

(NOTE: This is a reprint of an article that was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated October 7, 2019)

If Gandhi lives today, it is because of his enemies, who seem unable to let go of his memory. The Mahatma’s followers have turned him into a saint whose teachings can safely be ignored—as the words of a superior being to be admired from afar. Given the ritualistic respect offered to him in India and received with public indifference, it is puzzling why Gandhi remains such a living figure for his critics. Perhaps they are the only ones who still feel betrayed by his loss of sainthood. This betrayal is renewed in every generation, as scholars and activists discover yet another of the Mahatma’s failings.

In the wake of second-wave feminism, the Mahatma, during the 1980s, was excoriated for his views about women. The criticism was based on anecdotes about Gandhi’s treatment of his wife Kasturbai and his experiments with celibacy that entailed sleeping naked with young women. But these women’s voices are strangely silenced. Manubehn, who participated in Gandhi’s experiments, has left a diary that no critic has thought to read. While he was sometimes harsh to his intimates, it was also from Gandhi’s circle that many women entered public life—Anasuya Sarabhai, Mridula Sarabhai, Amrit Kaur, Sarojini Naidu and Sushila Nayyar.

In the 1990s, when the Mandal Commission revived caste struggle in India, Gandhi’s caste prejudice came into focus. But this did little more than recover B.R. Ambedkar’s polemics against him. Here, too, critics dwelt on anecdotes about the Poona Pact, when Gandhi fasted to deny separate electorates to lower castes, and his unconcern with any real amelioration of their plight. Yet, the Poona Pact was not only a caste issue, but emerged from the Minorities Pact between Muslims, Dalits and others that denied the existence of a nation in India.

The Mahatma’s critics may agree with Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Ambedkar about the absence of a nation in India, but resist recognising why Gandhi supported caste. As an anarchist, the Mahatma was suspicious of the state and its effort to remake society in a fulfilment of colonialism. He realised that castes, villages and religious communities were crucial if swaraj, or self-rule, was to be produced outside the state, which could not be allowed to dictate a national identity to Indians. For this, it was necessary to reform rather than reject such institutions, making Gandhi a conservative rather than a revolutionary.

Ambedkar started disagreeing with the Mahatma by arguing for the state’s absolute power to transform society, which is what allowed him to join hands with Jawaharlal Nehru. But he soon realised the excesses and limitations of such power, resigning from the cabinet to concentrate on promoting social change in religious terms, a move reminiscent of Gandhi’s career. Indeed, Ambedkar never forsook the Mahatma’s arch-concept of satyagraha, despite his clear and abiding hatred of the man who had called his bluff in forcing him to back down during the Poona Pact.

If Gandhi’s feminist foes silence women’s voices, his caste enemies erase the role of Muslims to make for a purely Hindu debate—many of Ambedkar’s arguments about nationality and representation being versions of Jinnah’s. His views about ‘backward’ adivasis and ‘fanatical’ Muslims, whom he wanted to deny separate representation, would also merit more censure were Ambedkar treated in the same way as Gandhi. Ambedkar thought his attempt to secure representation for Dalits was undercut by the Muslim League’s desire to come to an agreement with the Congress at their expense, as also by the colonial state’s promotion of adivasi representation to fragment Indian politics.

During his own lifetime, Gandhi’s enemies mounted arguments that were political rather than personal. They saw the Mahatma as anti-Muslim or anti-Hindu in ways that repudiated anecdotal evidence for more complex narratives. Even his assassin acknowledged Gandhi’s sincerity and attributed his supposed betrayal of Hindus to the attempt at repeating his success in unifying South Africa’s Indian community—having misunderstood the different conditions at home. The communist view of Gandhi as an agent of capitalism was complex and invoked Marx’s theories about the development of class conflict.

Colonial officials were the ones who pioneered the anecdotal and personal style of criticism that has come to define Gandhi’s enemies. For they accused the Mahatma not of any particular crime, but of being a consummate hypocrite in all he said and did. This focus on hypocrisy discounts an understanding of Gandhi’s words and deeds as a form of political thought to search for their meaning in fragmentary quotations and conspiracies. It is a way of understanding history characteristic of the far right, and signals the leftist critic’s collusion with them.

These varied and mutually contradictory condemnations tell us more about those who make them than the man who is their subject. Gandhi has become the origin from which each generation of Indians can trace the consequences of its social and political concerns. In this way, he remains the father of the nation. It is not surprising, then, that with its worldwide revival, Gandhi is now being accused of racism, of which Indians have now become agents rather than objects.

Unprecedented about the condemnations of Gandhi’s racism, however, is that they are not limited to India but have become global, with statues of the Mahatma attacked or removed in different parts of Africa as a result. Two charges are levelled against Gandhi. That he never spoke for the liberty of Africans or involved them in his movement. And that he saw Africans as inferior and sought to keep Indians separate from them. But unless he was invited to do so, the Mahatma never spoke for any community of which he was not a member. For he conceived of non-violence as an exemplary rather than instructive practice, one attracting emulation to maintain an anarchistic social plurality.

Gandhi’s South Africa was a society whose racialised populations were treated differently by law. As a lawyer defending Indian privileges, he was unable to challenge the legal system itself. And the law ensured he could only defend these privileges by making sure Indians were not identified with Africans, though he might well have approved of this separation. Yet, he also insisted on treating wounded Zulus in the ambulance corps he led during the Bambatha Rebellion, his political sympathies being with them and not with Britain.

When he was no longer a lawyer, Gandhi’s derogatory comments about Africans ceased. In his book Satyagraha in South Africa, he contrasted Zulus favourably with Indians on every count. Eventually, he would also see African-Americans as the most hopeful agents of non-violence worldwide. But given their legal status, the Mahatma had to fight for his compatriots as Indians. His demand was an international rather than South African one, and consisted of compelling India to uphold the status of her subjects in other parts of the British Empire.

Calling the Mahatma’s first satyagraha a South African one, as he himself did, is, therefore, something of a misnomer, as its traction depended upon India’s and, therefore, London’s involvement. South Africa was only one site of this struggle, with Gandhi interested in the status of Indians all over the British Empire, from Kenya to Mauritius, Guyana, Fiji and Trinidad. It became a global movement when he sought to and, in fact, succeeded in abolishing indenture, the Indian successor to African slavery which supplied labour for much of the Empire.

Perhaps Gandhi was a racist after all, but we get no sense of this from his enemies, whose personalised, and often conspiratorial, arguments deprive his thought of integrity and ignore the many contexts in which he operated. Even accusing Hitler of racism is a meaningless generality, since we can only understand his violence by taking its intellectual justification and historical context into consideration. Instead of merely turning the saint into a sinner, then, it is time for the Mahatma to become a properly historical figure for his friends as much as enemies.

—The writer is a professor of Indian history at the University of Oxford

Subscribe to India Today Magazine