Obituary: Soumitra Chatterjee

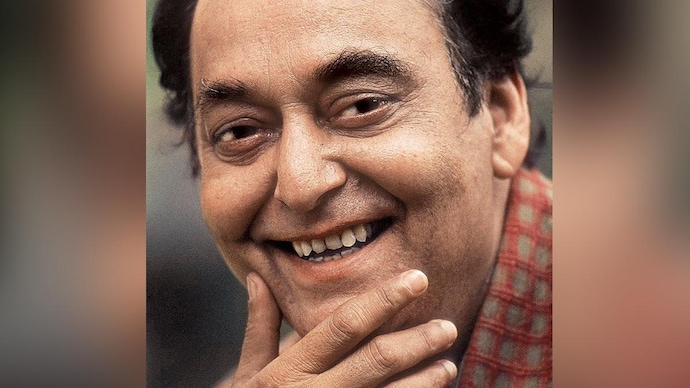

The Last of the Crew Soumitra Chatterjee, the face of Bengali art cinema, was known for his decency, intellect and passion.

There is a story from the 1980s’ filming of a political thriller set in Calcutta, directed by one of Bengali art cinema’s rising stars. This director, having seen all sorts of international cinema, from Costa-Gavras to Solanas, decided he needed his protagonist to make a call from a phone booth. Calcutta was never replete with phone booths but finally one was found in Howrah station. As the camera lights heated up, the young actor began to get cooked in the glass cage. Take after take failed till the director yanked open the door and shouted at the actor: “Why aren’t you thinking of Mastroianni!?! Try and remember Belmondo!!”

No director would have dared to ask Soumitra Chatterjee to mimic Italian or French actors. In the early 1960s, as he rocketed to international recognition along with his mentor-director Satyajit Ray, Soumitra found himself on an equal footing with other male icons of international art cinema, as originally Bengali and Indian as Mastroianni was Italian, Belmondo French and Mifune Japanese.

Ray’s films found critical praise in a post-war European art cinema circuit that consciously posited itself against the mega-bulldozer of Hollywood; Anglo-American film critics who studied these European films also began to appreciate works from other parts of the world and Ray’s films became regular offerings on American college campuses and art theatres. Leaving aside the traction enjoyed by Bombay films in the Middle East, Africa and Russia, for a period between the mid-’50s and early ’70s, Ray’s was the only serious Indian cinema recognised internationally, with Soumitra as one of its main figures.

For Bengalis, Uttam Kumar might have been the more adulated star, the better actor even, but for the world outside, it was Soumitra who was the face of Bengal and, for a long time, of India. With the early death of Uttam Kumar, Soumitra, with his patrician nose, glowing eyes and finely-wrought good looks, also became the one who distilled the archetype of a quietly heroic, romantic, graceful and morally-upright Bengali bhadralok of both the 19th and the 20th centuries. This was true not least for Bengalis themselves, you could look like Jyoti Basu or Pranab Mukherjee, but inside yourself you saw Soumitra. Uttam may have had greater sexual magnetism, Utpal Datta the deepest baritone, other stars may have had unique components, but Soumitra’s was the combination that trumped everybody. Off-screen, too, the man was known for his decency, genuine intellectual learning and passion, and to be totally lacking in the arrogance and pretensions that often encrust actors.

There were carpings and criticisms of course: Soumitra’s chiselled Bangla speech was far from how real Bengalis now spoke, that it was very “Ghoti”, i.e West Bengali, and from an educated class of another age; that as an actor his range was limited and disconnected from reality. But the counterweight to all this was the immense grace and fragility he showed in his early films, the almost Ardhanarishwar-like personas he created. Later, there was a solidification, a handsome not-so-young man beset by flaws and doubts, that had its own charm. Later still came the “mature” roles, but by then Bengal had picked up other, more macho icons to idolise and the “classic” Soumitra remained encapsulated in the works of the first 15 years or so of his career.

There are downsides to having a longish life. Soumitra lived to see the waning and extinction of the great artistic period to which he contributed so centrally. In 1958, when Apur Sansar was being made, Calcutta had the most vibrant cultural and intellectual life in the country; Bengali cinema was piggy-backing to greater heights, partly on superb Bengali theatre, with its tradition of great acting, directing, set design and lighting. In other fields, too, literature, art, academics, the city led the rest of the newly independent India. It was not to last. By the mid-’80s, a wave of mediocre directors were scrambling to copy western art films, making work full of cliched content. Starting with the passing of Ray in 1992, one by one, the lights of the fecund and dynamic Bengali cinema movement of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s began to dim and go out. Soumitra was the last of the diverse crew that gave us so many gifts, without worrying about what the Italians or Iranians were doing. For that we should be very grateful.

Ruchir Joshi is a Kolkata-based writer and filmmaker