GADADI, India — Chandrika Majhi had big dreams before the Covid-19 pandemic, when she was a 17-year-old studying commerce in the capital of the eastern Indian state of Odisha. But once the pandemic shut down her school, Majhi was forced to return to her family’s village, where there was no opportunity to continue her education.

Three years later, she now holds her 1-year-old son in her arms as she stands outside her hut in the village of Gadadi, tired from household chores.

“This is never what I thought I would be doing,” Majhi, a member of the Kondh tribal community who says her parents married her off against her will, said of having a child so young.

India, a multilingual and multiethnic country known as the world’s largest democracy, is expected to surpass China as the world’s most populous country by the end of this month, with an estimated 1.43 billion people, according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The U.N. Population Fund previously said that India would have almost 3 million more people than China by the middle of this year.

Though population growth is slowing in both countries, India’s youthfulness — about two-thirds of its population is under the age of 35, according to the International Labor Organization — means it will continue growing for decades. This has experts warning that women from Indigenous groups, lower castes and other marginalized communities often face greater obstacles in making their own reproductive decisions.

“Sadly, access to health services continues to be determined by factors such as where a woman lives, how educated she is, her wealth quintile, and the community she belongs to,” said Sanghamitra Singh, lead for policy and programs at the Population Foundation of India.

While India’s fertility rate has fallen as women overall gain greater access to education and contraception, population growth across India is uneven. Southern states like Goa and Kerala record lower rates than northern ones like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. The states with lower growth rates tend to have more education and employment opportunities for men and women alike.

But even in states like Odisha, where the fertility rate of 1.6 children per woman is lower than the national average, marginalized women struggle to advocate for themselves.

Sharada Majhi, who is also from Odisha’s Kondh community but has no relation to Chandrika Majhi, said she was jealous of her friends who continued going to school while her parents were arranging her marriage at age 15.

“I was a child myself when I had my first baby,” she said of giving birth the following year.

“I did not even know what sex is or what it leads to, let alone make a decision on whether I wanted a child,” she said.

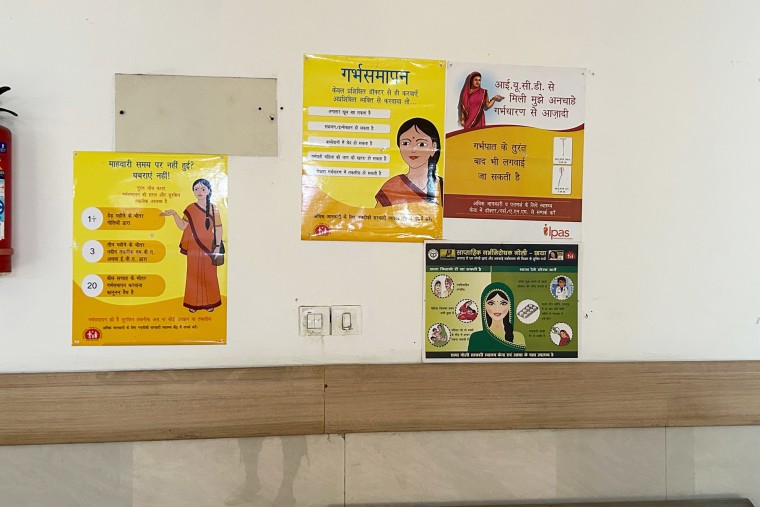

Government information about family planning tends to emphasize women’s responsibility. On a recent visit to the Gautam Buddh Nagar district hospital in Noida, a city in Uttar Pradesh that is next to New Delhi, the walls were plastered with posters on birth control pills, female sterilization and safe abortions, while only two mentioned condoms or male sterilization along with other methods.

Lack of awareness about other family planning methods has helped make female sterilization one of the most common forms of contraception in India. According to India’s latest National Family Health Survey, which was conducted from 2019 to 2021, it was used by almost 38% of women to prevent unwanted pregnancies, compared with 0.3% for male sterilization, which is less invasive.

Women’s lack of access to information about contraception, as well as men’s relative lack of engagement in family planning, “has placed an undue burden on women to address their health and reproductive needs, without really having the agency or autonomy to make their own health and fertility decisions,” Singh said.

A woman surnamed Valmiki, who declined to give her full name for fear of retribution from her family, is a mother of five from the Dalit community, India’s lowest caste, and works in sanitation in the Uttar Pradesh city of Meerut. She was never educated.

“I never knew that I could say how I felt about having more children. I only knew about tubectomies,” she said, referring to sterilization, “and they felt too permanent and I was scared.”

Some states, like Uttar Pradesh and Assam, are considering legislation aimed at slowing population growth that would restrict civil liberties and access to social welfare resources for people who have more than two children. In other states, people with more than two children are ineligible to run for local office or apply for state government jobs.

Such policies are unlikely to be effective, Singh said.

“Any attempt to impose penalties is biased against the poor, the illiterate, and socially disadvantaged groups in society, the same groups that have historically faced discrimination and neglect,” she said.

A better approach, she suggested, would be to increase men’s involvement in family planning, “and have more girls and women get educated, join the workforce and delay marriage and pregnancies.”

Singh and others say India’s economy could be transformed by its working-age women, only 10% of whom were either employed or looking for jobs in 2022, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

“Building Indian women’s access to education and employment can be a game changer for a young India,” said Roshnara Mohanty, a social worker from Odisha.

A 2018 report from the consulting firm McKinsey found that India could add about $550 billion to its gross domestic product by increasing women’s participation in the labor force by 10 percentage points.

Sharada Majhi, now 35 and a widow with two young daughters, has since formed a collective of single and widowed women to advocate for their land rights, working for positive social change in a cluster of villages in Odisha.

“God knows what I could have achieved if I was given the opportunity to study more, to work more,” she said.