Notes of an Early Life – An Article by Alexander Graham Bell, July 2, 1921

Summary: Alexander Graham Bell’s article, “Notes of Early Life,” describes his first invention as a boy, which was a machine to clean wheat. He was inspired by his friend’s father’s suggestion to do something useful and, with his friend’s help, came up with the idea to use a rotating machine to clean wheat. Bell also shares his experiences founding a society for the promotion of fine arts among boys, collecting and studying animal specimens, and teaching his family’s dog to speak. He reflects on his early education, expressing a preference for nature study over classical subjects like Latin and Greek, which he found difficult. Bell credits his time living with his grandfather in London as the turning point in his life, as it motivated him to improve his education and pursue his ambitions. Alexander Graham Bell also reflects on his childhood and his relationship with his grandfather, who he lived with for a year after graduating from the Royal High School. Bell was impressed by his grandfather’s dedication to his education and the lessons he provided in elocution and declamation. During his time in London, Bell’s grandfather transformed his appearance into that of a gentleman, with tailored clothing, gloves, a silk hat, and a cane. This experience instilled in Bell a sense of independence, which he pursued by seeking out his own education and job opportunities. At the age of 16, he became a pupil-teacher at Elgin, where he taught Latin and Greek while also receiving instruction to prepare for university.

References:

- https://www.loc.gov/item/magbell.37500203/

- Image reference: https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3c04275

—

NOTES OF EARLY LIFE

From the Notebook of Alexander Graham Bell

I. MY FIRST INVENTION

When I was a school-boy my father had a pupil, Benjamin Herdman, who was of about my own age. We became intimate and used to spend a good deal of time together. Benjamin’s father owned a large flour mill, known as Bell’s Mills, near Edinburgh. I was at the mills a good deal with my friend Benjamin, and, as boys will do, we were constantly getting into mischief.

“Do Something Useful”

One day Benjamin’s father called us into his office and gave us a good talking to. He wound up with the words, “Now, boys, why don’t you do something useful? I mildly asked him what we could do. It seems that at the moment his mind was occupied with some problem concerning his mill, and he picked up a handful of wheat and said, “If you could only take the husks off this wheat you would be of some help.”

I said nothing at the time, but began to wonder whether some machine could not be devised that would remove the husks from the grains of wheat before milling. It seemed to me that brushing would accomplish this, so, through Benjamin Herdman, I quietly procured a sample of wheat and began to make experiments. I found no difficulty, by diligent application of a nail-brush, in cleaning the wheat as desired.

It then occurred to me that at Bell’s Mills they already had a rotating machine, used for other purposes, that should do the business. By dumping the wheat into this machine it would be paddled round and would be thrown against the circumference of the machine, which was provided with brushes or something rough that I thought would clean the wheat as thoroughly as the nail-brush had done.

Armed with the sample of wheat I had cleaned, Benjamin and I repaired to Mr. Herdman’s office and explained the idea to him. He seemed struck with the idea and immediately ordered the experiment to be tried. It turned out to be a success, and I have the impression that this method of cleaning wheat was permanently adopted in Bell’s Mills.

The Herdmans subsequently acquired the Haymarket Mills, in Edinburgh, which still belong to the family. Mr. John Herdman, a son of the old gentleman (who is no longer living), remembers the experiment, and can tell better than I what practical results ensued.

So far as I remember, Mr. Herdman’s injunction to “do something useful” was my first incentive to invention, and the method of cleaning wheat the first fruits.

II JUVENILE RESEARCH

School-boys are often fond of societies and secret associations with passwords and grips, and I was no exception. In addition to founding the great “ Frab” society, modeled upon Free Masonry, I also founded “The Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts Among Boys”.

There was no difficulty in obtaining members, so long as every member was an officer of the society. We had a president, vice-president, etc., and professors, but no common members. My brother Edward was professor of drawing and I was professor of anatomy. It seems rather strange at the present time that anatomy should have been included among the fine arts, but we boys saw nothing incongruous in the association.

I was honored with this special distinction from the fact that I was fond of examining the insides of all the dead animals I could come across. I had quite a collection of skeletons of small animals cleaned by myself, chiefly birds, but also including the higher mammals, like rats and mice! In the case of larger animals, like cats, I preserved the skulls only. My father encouraged me in making collections of various sorts, and helped me to arrange my specimens in some sort of order, which I supposed to be scientific.

I commenced with plants, and was encouraged by my father to arrange them according to the Linnean system of botany. Then I took up birds’ eggs, and was allowed by my father to collect them, providing I took only one from a nest and did not leave the nest empty. In time I had quite a collection of eggs, and made experiments in substituting the eggs of one bird for those of another in a nest. I placed a thrush’s egg in a small bird’s nest in our garden at Milton Cottage, but the young thrush when hatched took up so much room that he shoved out the other birds.

Then my fancy turned to anatomy and collecting the skeletons of birds. On one occasion my father presented me with a dead sucking pig, and the distinguished professor of anatomy was called upon for a lecture. So a special meeting of “The Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts among Boys” was held in my study, the attic of my father’s house (13 South Charlotte Street, Edinburgh). This was sacred to me, and there my collections presented an imposing array of anatomical specimens.

Some boards were arranged as seats for the members of the society. On a table in the middle lay the defunct sucking pig. It was a great moment when I started to thrust my knife into the abdomen of the subject for dissection. But, unfortunately, there happened to be some air in the creature, so that the knife thrust was followed by a rumbling sound that resembled a groan, with the result that we thought the creature alive.

Horror-stricken I rushed from the room, followed by all the boys. We tumbled over one another in our eagerness to get downstairs. Each boy fled to his home, and none returned to hear the lecture. Even the lecturer himself was too frightened to revisit the lecture-hall. My father was obliged to go upstairs and take charge of the corpse; I never saw it again.

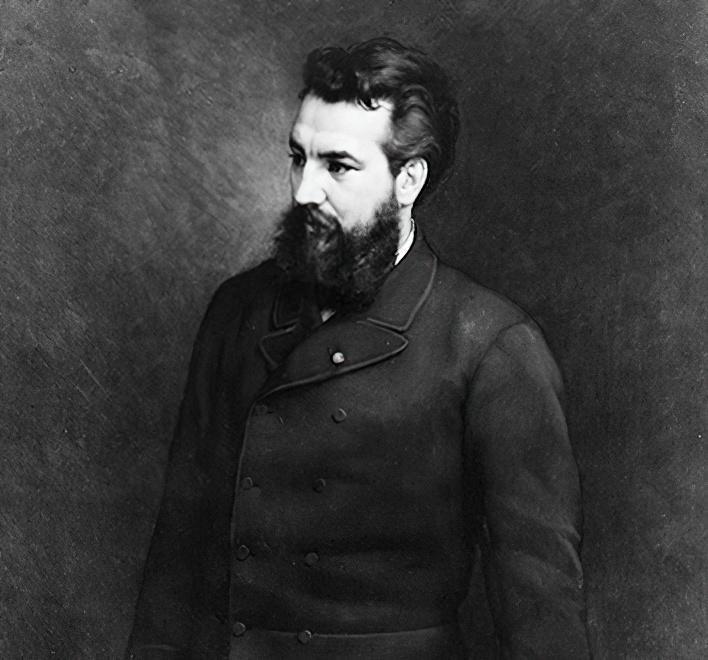

![Alexander Graham Bell. Timoléon Lobrichon, artist; photograph of 1882 painting. [between 1882 and 1960]. Gilbert H. Grosvenor Collection of Alexander Graham Bell photographs. Prints & Photographs Division](https://www.onlinesafetytrainer.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/photograph_of_a_painting_of_alexander_graham_bell_portrait.jpg)

Alexander Graham Bell. Timoléon Lobrichon, artist; photograph of 1882 painting. [between 1882 and 1960]. Gilbert H. Grosvenor Collection of Alexander Graham Bell photographs. Prints & Photographs Division

When I was a young man, about twenty years of age, I became much interested in the great diversity in the size and shape of the mouths of my father’s stammering pupils, and began to study the vocal organs of persons who had no defects of speech. A similar diversity was observable here, and I began to wonder whether the mouth of such an animal as a dog would be capable of producing articulate sounds. We had a very intelligent skye terrier, and upon this creature I began to make experiments.

I found little difficulty in teaching the dog to growl at command. His food supply was limited and he soon became delighted to growl for food. He would sit up on his hind legs and growl continuously until I motioned him to stop. He was then rewarded with a morsel of food. I then attempted to manipulate his mouth. Taking his muzzle in my hand, I caused his lips to close and open a number of times in succession while he growled. In this way he gave utterance to the syllables “ma, ma, ma.” He soon learned to stop growling the moment I released his mouth, in anticipation of the expected reward (which was never withheld). After a little practice I was able to make him say, with perfect distinctness, the word “mamma,” pronounced in the English way, with the accent on the second syllable.

I then placed my thumb under his lower jaw, between the bones, and, pushing up a number of times in succession, I caused the dog to pronounce the syllables “ga, ga, ga.” By pushing up the thumb once, and then constricting his muzzle twice in succession, he gave utterance to “ga, ma, ma.” By practice this was made to resemble, in a ludicrous degree, the word “grandmamma” (pronounced ga-ma-ma.) A double reward followed this result, and the dog became quite fond of his articulation lessons.

The dog’s mouth proved to be too small to enable me to manipulate other parts of his tongue, and I had to content myself chiefly with labial effects. By careful manipulation of the muzzle we obtained a sound that passed for “ah,” and, by finishing off the “ah” sound with a final “oo”, we obtained a diphthongal vowel that passed for “ow” (as in the word “now”). The culmination of his linguistic education was reached when the dog was able to say in an intelligible manner the complete sentence, “How are you, grandmamma”? (pronounced “ow ah oo, ga-ma-ma”).

The fame of the dog spread among my father’s friends, and many were the visitors who came to the house for the express purpose of seeing this dog sit up on his hind legs and, with a little assistance from my hand, growl forth the words, “How are you, grandmamma?” Indeed, his fame grew to such an extent that reports frequently reached me of success in articulation utterly unwarranted by the facts. I made many attempts, though without success, to cause him to produce the effects without manipulation. He took a bread-and-butter interest in the experiments, but was never able, alone, to do anything but growl.

IV LIFE WITH MY GRANDFATHER

After finishing my course at the Royal High School of Edinburgh, when I was about fourteen years of age, I went to London to live with my grandfather, Alexander Bell,, professor of elocution. He resided alone, at No. 18 Harrington Square, and I stayed with him for about one year.

This period of my life, as I look back at it, was the turning point of my whole career. It converted me from a boy into a man, somewhat prematurely. It made me ashamed of my educational status— which was by no means high— and stirred up in me the ambition to remedy my educational limitations by my own exertions.

Early Education.

My early education had been carried on upon the classical model, and I am afraid that I did not do justice to my excellent teacher, Dr. Donaldson, who is still living, as the president of St. Andrew’s University. For Latin and Greek, as taught in the school, I felt no taste. I was fairly interested in arithmetic, but, although I understood and mastered its processes, I was very inaccurate in my computations. I would know how to do a thing, but often got the answer wrong. I was quite fond of puzzling questions in proportion, and found little difficulty in that most difficult part of the problem, stating the proportion properly; but I found it a very different thing to work out the answer without error.

My natural bent was toward nature study, but this formed no part of the curriculum at school. I actually obtained by my own exertions, with the encouragement of my father, a fair knowledge of the Linnean system of botany when I was a small boy. In the same way I studied zoology by myself, although I presume that my father must have helped me, at least in acquiring the names of the natural orders of animals.

My interest in reading was divided between fairy tales and anecdotes of animals.

Unfortunately, neither botany, zoology, nor anatomy, nor any of the subjects in which I naturally felt an interest, were taught to me in school. I fairly hated Latin and Greek, to which great time and attention were given, and it seems strange to me now, considering my low standard in these subjects at school, that sufficient Latin and Greek were stuffed down my throat, so to speak, as to have been of inestimable value to me in understanding the etymology of the English language, and in giving me a key to the barbarous language of science, in which the terms are largely of classical origin. I was a fairly good speller, as a boy, and was fond of English composition, especially in the form of verse.

Indeed, I considered myself as something of a poet. My themes were taken from nature, generally referring to birds and animals. There was another boy at the high school, of the name of Weightman, I think, who was also addicted to verse. We were looked upon as the class poets, and on two or three occasions we had the honor of declaiming our compositions before the class. The accomplishment of versification was, I think, the only subject in which I distinguished myself at school. In reading or declaiming I stood fairly well in the class, but in all other subjects, especially in Latin and Greek, I took a low rank.

An Old Man’s Companion.

However, in spite of my disqualifications, I passed through the whole curriculum of the Royal High School, from the lowest to the highest class, and graduated, but by no means with honors, when I was about fourteen years of age. Then the visit from my grandfather took place. I was cut off from all association with young people and lived alone, with an old man, for a year. We became companions and friends. My grandfather made me study by myself, and gave me daily lessons in elocution and declamation. I read through a number of Shakespeare ‘s plays with him, and he made me commit to memory the most famous passages from “Hamlet”, “Julius Caesar”, and other plays.

When I reached London, my grandfather was somewhat disappointed with my appearance, not with that of my person, but with that of my clothes. My father and mother had been careful that I should be carefully dressed in Edinburgh, but, as they had anidea that city life was bad for children, and that growing boys should have plenty of fresh air, exercise, and freedom, impracticable in dignified Edinburgh, they had provided a country place at Trinity, where they {Begin deleted text}novels and take to study. I formed a{End deleted text} turned me loose in old clothes for at least two days in a week..

“Milton Cottage”, at Trinity, was my real home in childhood. There were always restraints against which children rebelled in the Edinburgh life of South Charlotte street. One of the greatest discomforts to us boys was the necessity of appearing properly dressed. My parents had taken great care in this respect, and it was as modifying to them as to me to find that my grandfather disapproved of my best Edinburgh clothes.

A Sartorial Rebirth.

Grandfather had me completely under his control from the time when my father brought me to London. The moment my father left for Edinburgh my grandfather sent for a fashionable tailor, and I soon found myself converted into a regular dude, resembling a tailor’s picture plate of an Eton school-boy. My coat or jacket resembled the swallowtail coat of today, with the tails cut off. I was obliged to wear kid gloves — a novelty indeed to me — and to cap the whole {Begin deleted text} {End deleted text} , I wore a tall silk hat, and carried in my hand a little cane.

I never had any young companions in London, but I was daily turned out alone in Harrington Square garden where I remained for an hour or so, sauntering up and down, feeling like a fish out of water, and suspecting that the passers-by on the public pavement were laughing at my appearance. I was never allowed to go out of doors without gloves, my tall silk hat, and my little cane. My grandfather impressed upon me the principle that I should never appear outside in the public streets, unless dressed as a gentleman.

Effects of the London Sojourn.

My life with my grandfather made me a studious and thoughtful lad, somewhat disinclined to associate with persons of my own age. From that time forth my intimates were men, rather than boys, and I came to be looked upon as older than I really was.

The shame regarding my ignorance made me throw aside fairy tales and plan for my own education, hoping to fit myself some day to go to college and take a degree. Of this educational plan I shall speak later, as it formed the basis of whatever real education I possess, for I never attended college, except to take a few courses of lectures and had no further formal education from others, save the year I spent in Elgin as a pupil teacher.

My father made me an allowance of pocket money, which I was free to spend as I chose. My grandfather never interfered with me, and I was thrown upon my own resources. In this way the spirit of independence arose in me, and, when I returned home, at about the age of fifteen, I chafed at the restraints of home life. I was treated as a boy again, when I had come to consider myself a man. I received no allowance after my return to Edinburgh, and all the money I spent was obtained upon request only.

My brother Melville’s frame of mind was similar to my own. Although we had a good home and most enlightened care from my parents, we were dissatisfied with home restraints and longed to be independent. On one occasion, when I was between fifteen and sixteen, I determined to run away from home and go to sea. My clothes were packed and I had fixed the hour of my departure for Leith where I expected to stowaway on a vessel. But better thought prevailed, and, at the last moment, I gave up the project. Then I began to search the newspapers for advertisements of positions that could be filled by one of my age.

The First Position.

Thus I found that a pupil-teacher was wanted at Weston House Academy, in Elgin, Morayshire. My brother, Melville, and I both answered the advertisement, simply signing our name as “brothers,” and giving our father’s name for reference. The advertiser, Mr. Skinner, turned out to have been a former pupil of my father, so he set himself in communication at once, and my father discovered how deeply interested were Melville and I in becoming independent. It was arranged that my father should sent Melville to Edinburgh University for one year, while I was to go to Elgin as a pupil-teacher, receiving a salary of ten pounds a year and board, besides instruction in Latin and Greek from Mr. Skinner, to fit me for the University.

Thus I became a pupil-teacher at Elgin at the age of sixteen. Several of my pupils were older than I, but as I looked so much older than I really was, they never found it out.