Body Language

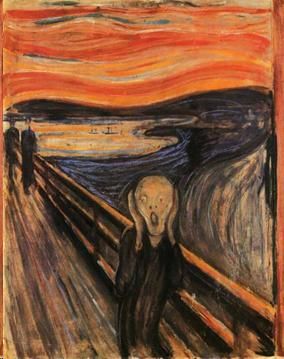

Munch’s Scream

What evolution and nonverbal communication studies tell us about an iconic image

Posted December 7, 2019

Edvard Munch’s extraordinary 1893 painting The Scream consistently places near the top of various lists of the most recognized and impactful works of art. It’s an iconic image, imitated and parodied countless times. Earlier this year, Jonathan Jones, a long-time art critic with The Guardian, described it as “the ultimate image for our political age."

While it is hard to disagree with this wry assessment, The Scream transcends politics, of course, and resonates with its admirers for more enduring reasons. Munch depicted a universal human emotional experience, strikingly raw and vivid, with the skeletal and androgynous figure’s face devoid of nuance or subtlety. Yet the remarkable purity and nakedness of the image leaves much to the imagination, as the artist surely intended. Why is our subject screaming?

There has been much analysis about the symbolism of The Scream, but, as far as I am aware, none of it addresses the question from the academic perspectives of nonverbal communication and evolution. I suppose fools have just not rushed in, but let’s dare to tread for the fun of it.

I am a behavioral biologist whose formal training and expertise lie far from art. However, for many years, I have studied animal and human screams, and I am intrigued by Munch’s painting. What insights might emerge from a biological perspective?

Screams are highly pertinent to our species: They instantly get our attention. The Scream portrays an act of communication, so let’s try to decipher it as such, taking advantage of the clues and cues available to us.

Dating back to Darwin, emotional communication has been explored extensively. Despite this long-standing interest, there is considerable debate today about exactly what one can infer about emotion from facial expressions. The belief that there are cross-cultural, basic human facial expressions associated with a set of core emotion categories, put forth by American psychologist Paul Ekman, has been highly influential over the last 50 years.

Lisa Feldman Barrett and her colleagues (Barrett et al. 2019) have questioned this widely accepted notion and, in a recent review of the available empirical evidence, advocated for more caution about how the face relates to emotion. They note, to mention just one of their many discussion points, that the supposed conventional fear expression, which involves a wide-eyed, gasping face, is instead interpreted as an expression of threat and anger by the Maori of New Zealand and by the Trobriand Islanders in Papua New Guinea.

Without going further into the debate about the face and emotion, for the time being, my point with respect to Munch’s screamer is that, based on the visage itself, we cannot identify with any great confidence the exact emotion experienced by our subject. So, for example, would you agree with me that the screaming Beatles fan (below) from 1964 looks somewhat like Munch’s subject? If so, this may or may not be evidence that the two screamers are experiencing comparable emotions, depending on whether one subscribes to Ekman’s view or Barrett’s.

What other evidence might help with the puzzle? In animal behavior research, environmental and social context are frequently critical factors in figuring out what an animal is communicating. The fiery, portentous background of The Scream has been frequently noted in commentaries exploring the painting’s meaning. Munch himself wrote about the inspiration for the painting, describing an Oslo evening walk with two friends and the sudden feeling of melancholy and anxiety stimulated by the brilliant, blood-red sky as the sun set over the fjord.

From a contemporary and personal perspective, I can look at that sky along with that face and instantly feel anxiety about climate change and global warming, but clearly Munch had other things on his mind. The distant people on the bridge seem oblivious to whatever is going on, so we’re left to conclude that our subject, too, is experiencing something very personal.

With respect to that flaming background sky, it’s noteworthy that Munch included it, with virtually identical detail, in two other paintings, Despair (1892) and Anxiety (1894), both part of his series on human emotions. However, the individuals portrayed in these paintings differ from the one seen in The Scream, so despite the similar setting and background, we don’t benefit in our detective work as we would if we could observe the same person expressing different dimensions within the broader constellation of shared affect and arousal that these three paintings depict.

But one critical source of information is impossible to secure: What did that scream sound like? The wide-open mouth strongly suggests that an actual vocalization is being produced. Does The Scream portray internal psychological disarray, fear, angst, and alienation, or personal dread? Is, indeed, that famous scream an expression of exasperation about the dystopian state of the world?

Is the screamer male or female, young or old? We would most likely know a lot more about that particular scream if we could hear it! But even then, we still might not be absolutely certain. People scream in a variety of contexts (e.g., surprise-startle, fear, pain, frustration-annoyance, aggression-anger, excitement-exhilaration, and, sometimes, sex). Whether we use acoustically different kinds of screams in these various situations, and whether we can discriminate between those screams and interpret them, is a focus of some of my ongoing research.

And when it comes to screams, we’re not alone, of course. Many species scream in a manner that we humans readily recognize, and these vocalizations most likely first evolved as a way to startle an attacking predator and provide a chance to escape. Screams are widespread: Birds scream, lots of different mammals scream (including some species that don’t have many other vocalizations, rabbits, for example) and there are even species of frogs that scream when grabbed! In some social animals, screams also evolved as a means to recruit help when a victim is attacked by members of its own species.

Research (including some of my own) on several species of monkeys suggests that an attacked individual’s screams recruit assistance from its kin and allies. These loud and distinctive vocalizations provide information about the victim’s situation to its supporters, even when they are some distance away.

But only we humans scream in such a variety of contexts. Animals scream at predators and when squabbling and recruiting allies, evolutionarily important situations, but fixed and quite limited usage. Photoshop a screaming monkey into Munch’s painting (a quick internet search yields many such animal parodies out there), and we would be reasonably confident about what triggered the scream.

Curiously, we know much more about animal screams than we do those of our own species. Perhaps this uncertainty of meaning helps make the scream in Munch’s painting (much like the ambiguous smile in the Mona Lisa) such an eternal work of art. My ongoing research and some of the topics I will focus on in future entries here will explore precisely what kind of information humans do communicate when they scream—and why we evolved to communicate in this fashion.

References

Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2019). Emotional expressions reconsidered: Challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20, 1–68. doi:10.1177/1529100619832930