Modern & Contemporary South Asian Art

Modern & Contemporary South Asian Art

PROPERTY FROM A PRIVATE AMERICAN COLLECTION

RAJA RAVI VARMA | UNTITLED (SWAMI VISHVAMITRA IN MEDITATION)

Auction Closed

March 16, 05:19 PM GMT

Estimate

700,000 - 900,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

PROPERTY FROM A PRIVATE AMERICAN COLLECTION

RAJA RAVI VARMA

1848 - 1906

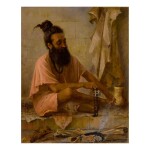

UNTITLED (SWAMI VISHVAMITRA IN MEDITATION)

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated 'Ravi Varma / 1897' lower left

30 ¼ x 24 in. (76.8 x 60.9 cm.)

Painted in 1897

Collection of Fritz Schleicher

Thence by descent to Mrs. Lotti Schleicher Singh

Acquired by a private collector in Denmark

Sothebys London, 8 June 2000, lot 110

Fritz Schleicher was a German printer from Berlin, who managed the 'Ravi Varma Oleographic and Chromolithographic Printing Workshop' and later bought the printing press from Ravi Varma in 1903.

Although Raja Ravi Varma developed his fortunes as a master portrait artist for the upper echelons of royal society in India, he achieved fame as a pioneer of popular culture, responsible for the mass dissemination of a new visual vocabulary through oleographs. By infiltrating the majority of households with his paintings and prints, he was essentially responsible for influencing and shaping perceptions for generations to follow. In addition to his unsurpassable talent, he depicted characters from ancient religious and mythological texts that resonated with the Indian people, a sure-fire recipe for success.

Varma was first taught painting by his uncle Raja Raja Varma who had achieved a modicum of fame as a painter himself. The colonization of India attracted a large number of European artists who were drawn to the wonders of what they considered to be an exotic and alien culture. These artists brought with them superior artistic materials including oil paints and canvases, the portability of the easel and rigorous academic knowledge and training. His uncle brought a young 14-year old Varma to the palace at Kilimanoor and introduced him to the Maharaja at the time. He was permitted to stay there, practice and study the royal collection of both local and European paintings. A few years later, Varma married into the royal family, cementing his connections and allowing him the opportunity to further study the art books at the palace and improve his English. Wary and jealous of his emerging talent, the few painters of the court who worked with oil refused to teach Varma this new medium. It was a European court painter Theodore Jensen who finally allowed him access to watch him paint. Experts such as A. Ramachandran (who was the force behind a grand exhibition in 1993 that revived the idea of Raja Ravi Varma as the father of modern Indian art) have since posited that Varma’s talent in the treatment of the human form itself was far superior to that of Jensen’s, adding to the notion that Varma was one of the most talented painters of that century. Varma exploited the material promise of oil painting like no one else. Prominent restorer and curator, Rupika Chawla who has conserved many of Varma’s works articulates, “No other Indian painter, till today, has been able to supersede Varma in portraiture in oil, a foreign medium, which the artist mastered over time through trial, error and hard work, while understanding the blending, smoothening and the play that was possible with this slow drying substance, a limitation its own right… The radiological evidence of Varma’s paintings shows the build-up of layers. His luminous skin effects are brought about by an excessive use of white in the preliminary layers gradually adjusted with flesh colors…With each passing decade the potential of oil was absorbed and understood by successive generation of artists in India. Today….all this excitement over oil and impasto techniques appears excessive… [though], a hundred years back it was like a discovery for an almost self-taught artist.” (R. Chawla, ‘Form and Substance,’ Raja Ravi Varma: New Perspectives, National Museum, New Delhi, 1993, p. 119, 122)

Later, in 1894, after producing a large number of oil paintings, Varma founded India's first oleography press in Lonavala. Known as the Ravi Varma Oleographic and Chromolithographic Printing Workshop, he succeeded in making his artwork available and accessible to the public, revolutionizing the placement of art – typically relegated to the court or temple – into everyday homes. To help reproduce his paintings, Varma employed Fritz Schleicher, a German printer from Berlin, highly qualified in color lithographic printing to act as manager of the workshop. Varma eventually sold the Press to Schleicher in 1903, at which stage the firm was renamed The Ravi Varma Fine Art Lithographic Works. Schleicher had twelve children, the youngest, a daughter named Lottie, who had started her education in Berlin, but with the rise of Nazism, moved to a private school in Vienna. In 1941, Austria was in the throes of World War II, which forced her to move to India with her fiancé, Dr. Surendra Singh. Mrs. Lottie Schleicher Singh inherited a group of works from her father from where this exceptional painting hails.

The current lot depicts Brahmarshi Vishvamitra in meditation. He is a famous and much venerated sage in Indian history. The oldest and most sacred collection of Vedic hymns written in Sanskrit is called the Rigveda and Vishvamitra is credited with having written a significant part of it. Vishvamitra was a king before he renounced his throne to become a sage. In one legend, King Vishvamitra meets a powerful sage Vashista. Vashista feeds the king and his entire army using a magical calf gifted to him by a God. Vishvamitra asks for this magical calf and when Vashista refuses, he steals it anyway. Vashista uses his immense powers to bring forth an army to defeat Vishvamitra and reclaim his calf. Awed by the power gained from meditation as a sage, Vishvamitra undertakes his own meditation or tapasya for several years and is bestowed with the knowledge and ability to use celestial weaponry. With these newfound powers, he seeks out Vashista and attempts to destroy his temple and his progeny. In another story, Vishvamitra tries to create a second heaven during his tapasya which frightens the Gods. They send a beautiful celestial nymph – Menaka to entice him out of his meditation. She succeeds in breaking his concentration and they end up falling in love. It is clear that Varma was quite taken with the legend of Vishvamitra as he painted multiple versions of him and some with Menaka as well.

Here, Vishvamitra is portrayed deep in the throes of meditation. His eyes are closed as he manipulates the prayer beads through his fingers, not noticing the dying embers of the fire. The background is free of much ornamentation, a vessel and some torn clothes all speak to the ascetic life he leads. As austere as his surroundings may be, the subject and nearby objects are depicted with incredible attention to detail. The knotted hair and beard, the folds amongst his clothes, the light and dark tones on his flesh and the nuances within the pieces of wood are all rendered with phenomenal detail and dexterity. In this painting, the artist has melded the tenets of Indian mythology while incorporating the contrast, detailing and color palette of Old Master paintings. It must be said that with the absence of color photography, and in fact the rarity of even black and white photographs at the time, paintings served as a faithful window to the world and the best artists were the ones who brought the mundane to life. This painting is one of the finest examples of this mimetic approach to art.

‘He selected easel painting and the oil medium over established Indian methods and materials, academic realism over the subtlety of suggestion as prescribed by ancient Indian treatises. But he also understood the power of the epics and classical texts that he had grown up with, and which his environment had so generously bequeathed to him. With the rich and plastic oil medium and realism as his tools, Varma transferred the wealth of stories and mythology that came so naturally to him, into paintings of great resonance.’ (R. Chawla, ‘Exploring the Source,’ Raja Ravi Varma: Painter of Colonial India, Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, 2010, p. 158) His use of color and paint is unparalleled for an artist from this period, which makes Varma’s works so desirable.