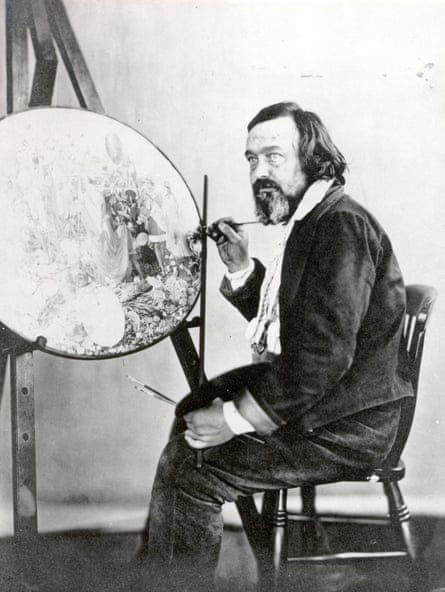

In his 2011 book about Richard Dadd, the art historian Nicholas Tromans notes that the artist seems to belong to the early 1970s, when he was recruited as “a heroic Victorian countercultural ancestor... a perfect case study for the anti-psychiatry movement”. He’s right about this historical moment, though Dadd’s then popularity surely derived as much from his subjects as from his extraordinary story (a paranoid schizophrenic, in 1843 he cut his father’s throat with a knife and was thereafter confined to an asylum until his death from tuberculosis in 1886). The florid supernatural landscapes of his imagination chimed with the tastes of the young couples who were doing up dilapidated old houses in industrial cities, prog rock on their turntables and William Morris on their walls. Thanks to one of these couples – my parents – he was the first artist whose work I knew. A postcard of The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855-64) was propped on a mantelpiece throughout my childhood. Even with my eyes closed, I could trace every demon, every beldame, every daisy, every hazelnut.

The Fairy Feller appears right at the start of the most ambitious retrospective of Dadd’s work since the Tate’s 1974 show, an exhibition curated by Tromans for the Watts Gallery, near Guildford. There it hangs, sinister and fascinating, its secrets cracked open for the visitor by means of a little technical wizardry (its finer details are projected on a wall) and extracts from the long poem Dadd wrote in an effort to explain it.

Move on, though, and you’ll discover that this show is not fixated by Queen Mab and her chestnut carriage. Its main focus is on the relationship between Dadd and Dr Charles Hood, who became the resident physician-superintendent of Bethlem in 1852. Hood modernised the asylum that was Dadd’s home, abolishing restraint and enabling some of the insane to exchange the dingy criminal blocks for brighter quarters: an engraving of the male ward in 1860 reveals bird cages and chess games. He was under no illusions about Dadd, who remained at Bethlem until 1864, when he moved to Broadmoor. In his notes, Hood referred to his notorious patient as a “thorough animal” whose delusions continued unabated. But he was also Dadd’s patron, the owner of some 33 of his works.

This exhibition includes several paintings from the period, before Dadd went mad, when he was still considered the brightest young artist of the age. Puck (1841), the canvas with which he made his name, is here, its rendition of moonlight so technically perfect a spell might have been cast. So, too, are several of the watercolours inspired by his ill-fated tour of the Middle East with Sir Thomas Phillips (it was while travelling that he first fell ill). But at its most fascinating, all roads lead to Dr Hood. Tromans believes that the Portrait of a Young Man (1853) is a painting of the doctor, a hunch that, if true, gives the garden in which he sits – a sunflower the size of a beanstalk looms behind him – a feverish new intensity. The man in the picture looks kindly, but he is (alarmingly for Dadd, perhaps) elsewhere.

Equally startling are the Sketches to Illustrate the Passions (1853-57), a series of 32 watercolours of which Hood owned 16. It is as if Dadd were using them to upbraid his doctor. Are the causes of insanity really so easy to categorise? he asks. Agony – Raving Madness (1854) satirises the Victorian view of lunatics, our patient a grimace in chains. The silvery shades of Grief or Sorrow (1854) conjure a 20th-century romantic such as Ravilious, until you notice that above the graveyard tomb it depicts hovers the skeletal figure of death.

This is a small but deeply satisfying show, something lovely around every corner: Contradiction: Oberon and Titania (1854-8), a teeming painting often seen as a companion piece to Fairy Feller, has been lent by a private collector; A Lady With a Minstrel (1870s) is a mysterious late picture that turned up on eBay priced £200.

Finally, at the exhibition’s close, are the prize certificates Dadd was commissioned to engrave by the physician Alexander Morison in 1865 for awards to humane psychiatric nurses. They show the patient “before” and “after”. In the former, the patient clutches at the air, bare of breast and wild of hair. In the latter, patient and nurse are indistinguishable. Poor Dadd, a talker of gibberish to the last, never pulled off this transformation, and it tears at the heart to see that he knew it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion