Bhupen Khakhar was born in Khetwadi in Bombay in 1934. His father was an engineer, and he died when Khakhar was still a child. Whenever I read Khakhar’s biographical details – he died in 2003 – I stop short at “Khetwadi”, where a Gujarati tailor my mother courted for his skill at making perfect blouses lived and worked in a room by a bridge. Khetwadi didn’t fit in with my idea of Bombay. Although it was notionally in South Bombay (the term didn’t exist when I was growing up, and now denotes the richest urban setting in India), it was distinct from it, as were the bazaar localities beyond Nana Chowk and Grant Road. Khetwadi was a small town in a big city, one of the many provincial settlements in a Bombay that made claims to be a great cosmopolitan metropolis. I ask my mother, who is now 90, the tailor’s name, and she says, without hesitation, “Madhavlal”. His face comes back to me: gaunt, bespectacled, his stubble kohl-dark, a pencil lodged behind one ear. When he came to deliver blouses in Malabar Hill, he had the air of arriving from a different state. He hardly smiled, though this didn’t necessarily mean he was unhappy.

Khakhar, too, was Gujarati. I recall that Khetwadi had a large Gujarati contingent. Unlike Madhavlal, he was born into a middle-class family. Had Madhavlal been better educated, he might have turned to one of the two vocations, or professions, that figured in Khakhar’s life: accountancy (Khakhar qualified as a chartered accountant in 1956) and art (he took an MA in art criticism from MS University, Baroda, in 1964, and was introduced to the art world there by his friend, the painter Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh). After all, the master tailor requires both the artist’s instinct and a head for measurement and precision (thus, the pencil behind the ear). On the other hand, it seems that Khakhar wanted, on some level, to be Madhavlal. It’s a droll middle-class fantasy – to want to be taken out of yourself in order to become whatever it is you’re escaping. Khakhar left accountancy for art and Khetwadi for Baroda more or less simultaneously. In the extraordinary paintings that followed, he would endlessly revisit the small-scale and the provincial, and gaze adoringly, from various perspectives, at the Madhavlal-like figure.

These bare facts of Khakhar’s childhood and youth don’t take into account details revealed to him by a holy man in Patna: “For being unfaithful to his wife, a previous incarnation of Bhupen Khakhar was murdered by his feudal lord. It was his daughter with whom the act of infidelity had been committed. As a punishment for his sin, he was born a butterfly. In that form he (or she) flew into a saint’s puja lamp. The unintentional sacrifice led to rebirth as Bhupen Khakhar at 7am on 10 March 1934, a Brahmakshatriya destined to become a chartered accountant and painter.” This information appeared in one of Khakar’s early exhibition catalogues – a catalogue that the poet Nissim Ezekiel, in “The Eccentric Genius” (probably the best essay written on this artist), said in 1970 was “a collector’s item, the most original and humorous of its kind in the history of modern Indian art. That Bhupen created it is altogether characteristic of the man. So are his invitation cards, posters, publicity releases and other paraphernalia of artistic self-advancement. He designs them as self-mocking, satirical replicas of bazaar culture ... The butterfly has come a long way.”

Khakhar was an artist in a then century old avant-garde Indian tradition of playfulness – so the reference to 4th‑century Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou’s celebrated butterly dream is unlikely to be accidental: “Once upon a time, Zhuang Zhou dreamed he was a butterfly ... flitting about happily enjoying himself. He did not know that he was Zhou. Suddenly he awoke, and was palpably Zhou. He did not know whether he was Zhou, who had dreamed of being a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming that he was Zhou.” Khakhar’s parable and the Chinese one are meant to remind us both of the randomness that sees a Gujarati accountant become an artist and of the essentially metamorphic nature of Khakhar’s sexual life – for he was gay. After visiting England in the 1970s, and coming into contact with both a more open social space for homosexuality and the paintings of David Hockney, he began to explore, and achieve, striking visual metaphors for “coming out” (what better term is there for the emergence of a butterfly?). This is not to ignore that Khakhar also found England “grumpy”, and blamed it for exporting to India a Victorian morality that, in his eyes, replaced a more hospitable environment for his sexuality. The 1981 painting after which a new Tate Modern exhibition is named, You Can’t Please All, takes its title from a fable by Aesop, and has a figure leaning from a balcony, naked, as if fresh out of the chrysalis.

The two butterfly dreams shouldn’t give us the impression that Khakhar believed in flitting about unfettered. The world – milieu, neighbourhood, lane, room, house, body, whatever we live and clothe ourselves in – is everything to him. This is what made him deeply attractive to certain writers: the poets Ezekiel and Adil Jussawalla; the novelist Salman Rushdie. It’s what drew me to the work. Khakhar’s figures are never really naked, even when he depicts them nude in numerous luminous and funny homosexual encounters. The body, like the room or the shirt, is another thing we dwell in; it too, for Khakhar, clothes the soul and the entrails. Its recurrence in the pictures is a reminder of Khakhar’s abiding love of what is called rupa in Sanskrit: the form and appearance of things. On the other hand, clothes and things made of cloth are everywhere as metaphors for the body: being stitched, of course, but also folded and left in the balcony, as in Still Life With Shirts; and the various quilts that only partially veil Khakhar’s lovers. Ezekiel, in that early essay, enumerates the locations in which Khakhar’s “soul”, like the butterfly, wanders – no garden, but versions of Khetwadi: “in paan shops and Irani restaurants, in tailor and watch repair shops, in the offices of branch managers and assistant accountants”.

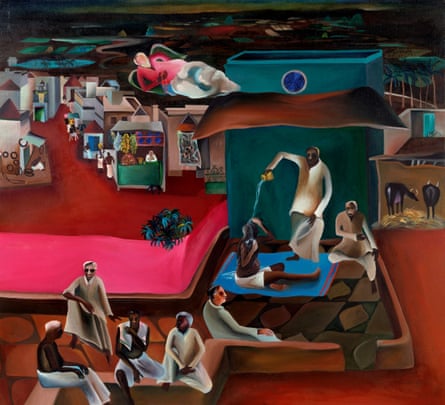

Khakhar’s paintings shun the metropolis proper; they portray excursions, liaisons, conversations, buildings, and ways of life in towns and neighbourhoods that are neither impoverished nor particularly desirable as places to move to or visit, unless it’s for a homecoming, or to look up relatives, or to track down Madhavlal. A host of visual models are discernible – the popular posters representing pilgrimage sites (except the constellation of sacred destinations are replaced here by verandas, terraces and alleys); calendar images, and the opportunistic ways in which they incorporate and reject perspective; Gauguin; Henri Rousseau; the Manet of The Bathers on the Seine. To these I’d add the images painted in the caves of Ajanta more than a millennium ago, deliberately unfinished episodes depicting the Buddha’s life in its various stages and reincarnations. When my wife and I first saw these, she noted spontaneously how India’s culture, on the evidence of the resplendent fading likenesses from the second century BC, was always urban – before us, on the dim walls, were balconies, windows, terraces overlooking other terraces, women absorbed in their toilette inside rooms. She and I belonged to a generation that had grown up with an untested idea bequeathed to us by another Gujarati, Gandhi: that the “true” India always was, and would be, in the villages. The frescoes in Ajanta tell us something else. Khakhar’s art, with its vernacular, bourgeois joie de vivre, is a liberating and comic rejection of Gandhi’s asceticism and his cantankerous fetishisation of the “natural” on behalf of the wayward life of civic spaces and an idiosyncratic fetishisation of the “unnatural” and manufactured. Nature doesn’t interest Khakhar; culture does. Early on, he noted the importance of plastic flowers in a quasi-surrealist but resolutely Indian manifesto, and gave expression to this article of faith in the wonderful and self-explanatory Man With Bouquet of Plastic Flowers. Yes, seas, rivers and landscapes occur in the paintings, but often with the flattened eccentricity of posters; while the pictures in the rooms he paints might depict seas, landscapes and rivers. This constitutes a specifically Indian middle-class reciprocity with the world.

Khakhar’s besotted and provocative eye for kitsch needs to be placed within the tastes of the 20th-century Gujarati Hindu community, whose achievements were largely, sometimes heroically, mercantile: think of the Patels who, after being expelled from Uganda in the 1970s, transformed Britain. There is a preference, in this context, for nylon, the now near-extinct Terylene, chiffon, plastic figurines and sumptuously realistic representations of the gods. This often involves a superstitious confluence of plastic, kitsch and divinity. The sacred is made available through posters. Khakhar, in borrowing from plastic and the reality-inducing colours painted on it, at once mocks, mimics and internalises the devotion they excite. His reworking of kitsch is, as a result, subtly overlaid with that misplaced sacredness. His imagination comes alive at a moment when the bazaar dimension of bourgeois culture is both a part of Indian modernity and is an embarrassment to it; it still isn’t an element in a cultural progression leading to the Bharatiya Janata Party. It’s replete with mischief and innocence.

I’m reminded, looking again at the work, of the exceptional viability of the human figure in modern Indian art. Granted, the tradition produced abstract painters, and its ancient non-representational lineage contributed powerfully to western art’s turn from conventional realism and perspective at the end of the 19th century. For all that, the figure in the Indian art of the last hundred years must count among the richest and most unexpected inheritances of secular modernity, and Khakhar possibly its greatest and most generous, most seductive, pioneer. This inheritance arises from being both shaped by and severing ties with the European Renaissance, with its photographic realism and insistence on putting the human being at the centre. All the great Indian practitioners of the figure – Tagore, Amrita Sher‑gil, FN Souza, Jamini Roy, Paritosh Sen, KG Subramanyan – rejected what the prodigiously gifted, short-lived, sharp-tongued Hungarian-Indian Sher-gil called “academic naturalism”, which she characterised as a style that believes “the sole function of painting and sculpture is to reproduce a given object faithfully, that is, with as much cretinous minuteness and servility as is humanly possible”. Khakhar’s tailors and watch-repairers have expressionless faces not because of an inner ennui, but because they have been released from the “servility” of realism: they are essentially humorous. The figures’ neighbourliness (all the humans and objects are conjoined by ties of friendship, family, sex and appetite) makes them strikingly different from Hockney’s on the one hand, and Francis Bacon’s and Lucian Freud’s on the other. In Khakhar’s world we discover in abundance the freedom of space and play that Sher-gil so desired from Indian art and life.

- Bhupen Khakhar: You Can’t Please All is at Tate Modern, London SE1, from 1 June. tate.org.uk.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion