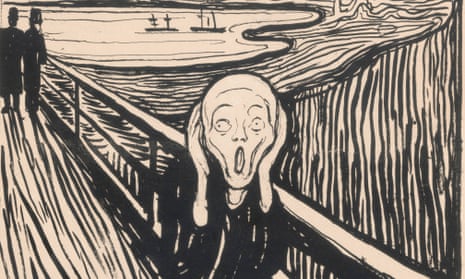

A rare lithograph of Edvard Munch’s most famous work, The Scream, will feature in the biggest UK exhibition of the artist’s prints in 45 years.

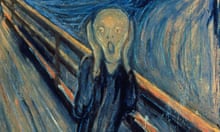

Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, at the British Museum from April, will explore the Norwegian’s expression of complex, often fraught, human emotions. At a time when Monet was painting landscapes, Munch was depicting love and desire but also jealousy, loneliness, anxiety, grief and mental instability – most memorably in The Scream.

The version being displayed at the British Museum is a black and white print, which followed a painting and two drawings of the image, but is the image that was disseminated widely during his lifetime and made him famous.

Describing the timeless relevance of The Scream, the exhibition curator, Giulia Bartrum, said: “The emotional impact is incredibly important. Munch was deeply, deeply aware of mental instability, mental illness, a huge subject at the time, and that’s what he was trying to portray. Anything which tries to express the inner workings of the mind … has huge resonance today.”

The Scream will be shown in the Anxiety and Separation section of the exhibition, which will also include a drawing, Despair, itself associated with Munch’s most famous work. Despair shows a figure turned away to look down into the fjords, which Bartrum said showed “perhaps the moment just before felt he heard the scream pass through nature”.

In accompanying text, Munch wrote of the blood red sky, also depicted in The Scream, and how the feeling of the moment resonated around the valley and in his head.

The same section also includes two versions of Angst, showing blank white faces streaming down Karl Johans Gate, Oslo’s busiest street, images Bartrum said would resonate with anyone who has felt lonely in London.

The exhibition features 83 artworks in all, including 50 prints from Oslo’s Munch museum. Other themes include women, with whom Munch had a series of disastrous relationships, and sickness.

Jealousy depicts the author Stanisław Przybyszewski in the foreground with a woman, presumed to be Dagny Juel, and a man with his back turned behind Przybyszewski. Juel is believed to have had a relationship with Munch before her brief marriage to Przybyszewski.

The artist’s mother died from tuberculosis when he was young and his sister also succumbed to the disease. For The Sick Child, three versions of which feature in the show, Bartrum said Munch “drew out his feelings of emotion at the moment that his sister died”.

She said the painting caused a scandal when it was exhibited in Berlin in 1892 because people were unused to such attempts to recreate the pain of the moment of death. The exhibition closed within a week, while at the same time proving popular with the avant-garde.

The exhibition also includes matrices used to transfer ink on to paper, never before seen in the UK, and will be displayed alongside the corresponding prints.

Bartrum said that for Munch, who never had children, partly because he feared they would suffer illness, his artwork served as a substitute and, unusually, he sought to collect the stones and wooden blocks, usually held by publishers.

“Certainly where these matrices were concerned, he behaved as if they were his family,” she said. “He wrote anxious letters about them, always trying to track them down.”

While the themes of Munch’s art resonate because of their timelessness, Bartrum, with an unsubtle nod to Brexit, said how the artist lived his life, during which he travelled to Paris and Berlin, bringing techniques and influences back to Norway, also served as an invaluable lesson in the modern age.

She said: “He was a really cosmopolitan European figure and I think, in this day and age, that is an important message to convey.”

Edvard Munch: Love and Angst is at the British Museum from 11 April-21 July 2019