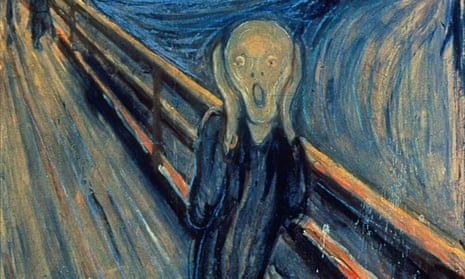

The face is a greenish sock of sickly flesh stretched tight over the skull. Its features have been burned away by pain. All that remain in the elongated mask are two wide round eyes with dots for pupils, a pair of black nostrils and a mouth open in an oval scream. We’ve all been there.

The Scream was created by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch in 1893 but it has become a masterpiece – the masterpiece – for our time. There are comparably “iconic” works of art – the Mona Lisa, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers – but they exist in a world of art and beauty. The Scream is ugly and brutal and belongs in the here and now. It is a symbol we reach for as we might for a strong word, to express what we’re feeling this minute.

The cartoonist Peter Brookes called on it to sum up what so many were feeling when Donald J Trump was elected president of the United States. In Brookes’s depiction of Trump’s inauguration, every single person in the crowd has metamorphosed into the wraith-like figure from The Scream. They sway in unison, hands to their hollowed faces, clad in black smocks.

You don’t have to be a professional cartoonist to express yourself with The Scream – you just need to text. The emoji sign “face screaming in fear” neatly sums up Munch’s image as a yellow face turning blue as it opens its mouth to scream, with eyes wide open, hands pressed to its cheeks in shock. It’s a handy emoji if you’re traumatised by Brexit … or climate change, or plastic in the oceans, or emojis.

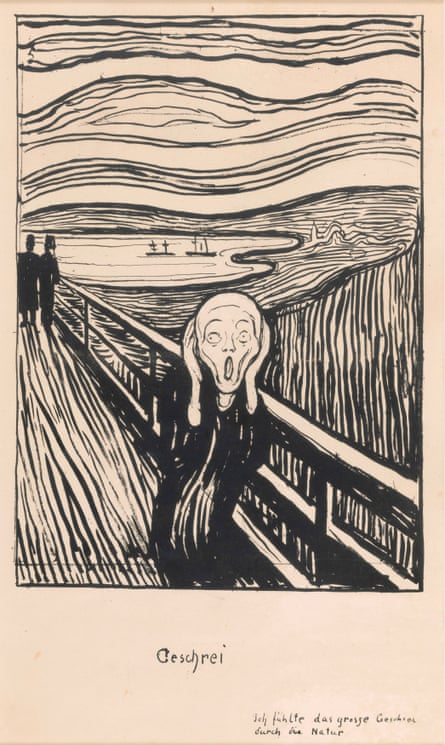

There are plenty of reasons to scream, says Hugo Chapman, the keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum. “Is that not the feeling of our time?” he asks of Munch’s image. Chapman’s department is usually where scholars fill out forms to study Rubens drawings or old maps of Somerset, but its announcement of a new exhibition has sent headlines spinning simply because Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, which opens in April, will include the 1895 lithographic version of The Scream. Chapman says the museum has not been surprised by the shrieks of excitement. “We have hit at a time of maximum anxiety that all of us feel incredibly strongly,” he told me on the eve of the meaningful vote in the House of Commons on Theresa May’s Brexit deal.

It is also a time of sardonic laughter, and surely part of the resonance of The Scream in these strange times is its comic hyperbole. A huge part of the global population was transfixed in the silent pose of Munch’s screamer on Trump’s inauguration day – and we still are – but there is also a blackly comic release in recognising our plight in this late-Romantic image. In fact, many appropriations of The Scream by popular culture are a howl. A chain of self-consciously youthful and riotous pubs called It’s A Scream used Munch’s painting as an advert for booze and bad behaviour. An artist called Robert Fishbone found a new sideline when he created an inflatable version of The Scream that became a must-have novelty for art students and existentialists everywhere. And in Wes Craven’s 1996 film Scream, which is at once a satire on slasher horror movies and a highly effective resurrection of the genre, the killer wears a white Halloween mask version of Munch’s screaming face. It is both ridiculous and gruesome.

These examples of The Scream’s irresistible rise in the shattered modern mind originated in the 1990s, which seems to have been the decade that saw Munch’s picture start its final ascent from a famous masterpiece of modern art to the most recognised, quoted and gazed-at icon of all. As a matter of fact, its triumph can be dated exactly. Today’s cult of The Scream started 25 years ago, on 12 February 1994. That was when thieves stole the original 1893 painting from Norway’s National Gallery. Detective Charles Hill, who was sent to Oslo from Scotland Yard’s specialist art squad to help get it back, remembers that it was not a very impressive heist: “It was two men and a ladder.” Detectives got in touch with the criminals and, astonishingly, convinced them that California’s Getty Museum was prepared to buy this piece of toxic contraband.

“I appeared as the man from the Getty,” says Hill. He negotiated with the crooks, refusing an offer to go somewhere unspecified with them, purportedly to see it, by dead of night, and ultimately helping to secure it just three months after it was stolen. Art crime may be ugly, but it is also popular recognition of a kind. You know you’ve made it when the criminal community rates your works theft-worthy. Although the Mona Lisa was always renowned, its theft from the Louvre in 1911 and recovery two years later catapulted it from genteel totem to pop icon. The theft of The Scream had a similar electrifying effect. It even started a gangland fashion. In 2004, masked gunmen seized Munch’s second painted version of The Scream, which dates from 1910, from the Munch Museum in Oslo. This time it took longer to get back, and suffered some nasty damage.

The 1990s also saw The Scream mirror a wider cultural mood. The end of the brash yuppy era brought a new emotional openness. Munch’s fin-de-siècle masterpiece suited another fin de siècle a century after its creation. Contemporary artists were returning to his themes of inner darkness with installations that used thick black crude oil, preserved animal bodies or a cast of a house. One Young British Artist, Tracey Emin, was consciously inspired by Munch in her confessional work My Bed, which is a kind of scream expressed through full ashtrays and empty bottles. Emin is now working on a seven-metre nude statue in homage to Munch that has been commissioned for the new Munch Museum in Oslo harbour, due to open next year.

If The Scream spoke in a new key to the late 20th century, the anxieties of this century, which started on 11 September 2001, have made it seem the most contemporary of all masterpieces. Its translation into an emoji is truly significant. The Scream emoji makes explicit the striking fact that it is getting hard to say the word “scream” without seeing The Scream. This painting is becoming part of the language. The Scream has become part of a shift to reconnect idea and images, to express ourselves in the internet age by direct visual icons. It is not just a painting that makes a good emoji. It is the original emoji.

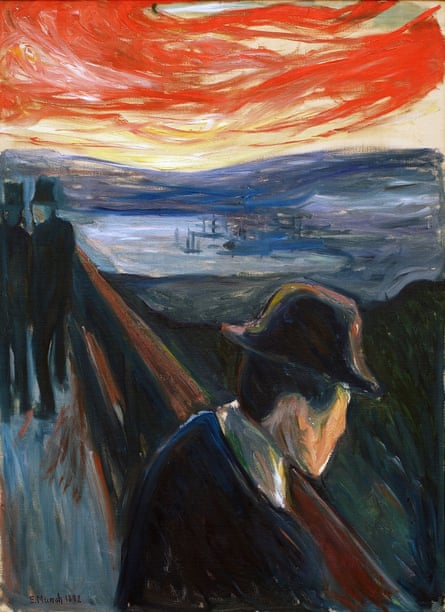

To see the revolutionary nature of Munch’s achievement, you only have to see how he first rendered into art the experience that The Scream records. In 1892, he painted Sick Mood at Sunset: Despair. It shows a man leaning on the wooden railing of a bridge, looking out on to a darkling blot of a fjord beneath a yellow sky smeared with red clouds of apocalyptic fire. Two other figures parade the boardwalk, leaving him to his depressed thoughts. The railings and walkway rushing away in steep perspective to the left of the scene, the paranoia-inducing figures walking away, the curve of the fjord – this is unmistakably the landscape of The Scream. For both paintings depict a real experience, a transforming, unforgettable moment of revelation. Was it an artistic ecstasy, like the visions of Romantic poets including Blake and Coleridge, or an episode of mental illness? In 1908, Munch wrote it down. He tells of how he was walking with two friends near Kristiania – as Oslo was then called – when the sun went down over the fjord. At the time, he writes, “life had ripped open my soul”.

Born in Ådalsbruk in 1863, Munch grew up in Kristiania amid poverty, puritanism and illness. One of his first paintings, The Sick Child, is a memory of seeing his sister die. As a young artist, he had to struggle with frequent illnesses, rejection, alcoholism and a tempestuous relationship in which he got shot. He was also witness to a murderous love affair among his bohemian friends. So as he looked at the sunset that evening, the sky split open not just in clouds of red but a bloody, volcanic, atomic rupture in the fabric of reality itself: “Then it seemed as if a flaming sword of blood slashed through the heavens’ vault – The air became like blood – with piercing strands of fire – The fjord – glared in cold blue – yellow and red colours – bloody red screeched – on the road – and on the railing – My friends’ faces turned glaring yellow-white … ”

This is the moment he depicts in Sick Mood at Sunset: Despair. In this painting, we see his anguish from the outside. The sky is gory, but it is in the closed mind of the man brooding with his face turned away from us that it feels like the end of the world. We see his despair, but it is not ours. We are like the audience watching Hamlet: involved yet outside his tragedy.

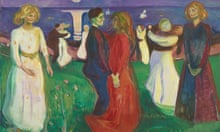

The following year, Munch obliterated that gap between actor and audience, artwork and onlooker. In 1893, he created his first two versions of The Scream. The one that is in Oslo’s National Gallery is done with tempera, that is, egg-based paints and crayon on cardboard. The other, in crayon alone, also on cardboard, belongs to the Munch Museum. In both of them, he simplifies his vision of the nightmare sunset into bands and nodules of colour, almost like the flow of woodgrain. More radically, he replaces his brooding man with a figure who has no identifiable sex and may even be a ghost or ghoul. Clad in a dark dress or tight robe, its face reduced to that caricature of dread beyond words, the screamer does not look at the mad sky but directly at us. It is us.

By removing all individuality from this being, Munch allows anyone to inhabit it. He draws a glove puppet for the soul. Absurd and empty, it is filled by the scream its mouth shapes – and that scream, claimed Munch, comes from the landscape itself. He testified that he truly heard a scream pierce the sky and fjord as he gazed on the terrible fiery sunset: “I felt a great scream – and I actually heard a great scream – The colours of nature broke up – the lines of nature – the lines and the colours – quivered in motion – These oscillations of light not only caused my eye to vibrate – they also brought my ear into vibration – so that I truly heard a scream – I then painted the picture Scream.”

In Norwegian it is “skrik”, whose jarring note sounds more like the English “shriek” than “scream”. The resemblance is no coincidence but clearly reflects the Viking infuence on our language. So Munch felt nature shriek. The imagery he uses is telling: as he watched, the light seemed to shake, the colours of nature to warp before or, rather, within his eyes. As his visual sense shook, it set off something in his ears. This is an instance of synesthesia, when experiences ramify through more than one of our senses. Munch was undergoing the kind of hallucinatory, multi-sensory, almost out-of-body adventure associated with visionary episodes from shamanism to psychedelia. It was part of a dangerous descent to the edge of madness that would eventually lead to him being hospitalised. And in The Scream, by creating a figure anyone can identify with, a pure embodiment of feeling, he lets us enter that same extreme state.

The Scream is so much more than a receptacle for the anxiety we’re feeling right now. It can rescue us. It offers a means of release from the grind and banality of politics, money and work. The true purpose of the greatest modern art is to reconnect us with demonic, ecstatic experiences that defy the boredom of modern industrial capitalism. Maybe Munch was possessed by the Vikings when he heard the world scream. For The Scream seems pagan and primitive in its shudder at the iciness of the empty north. It is a painting of Ragnarök – the Norse apocalypse. Which makes it even more the masterpiece for our time. Play Led Zeppelin’s Immigrant Song and stare at The Scream. You’ll soon forget all about the things that make you want to … you know.

Edvard Munch: Love and Angst is at the British Museum from 11 April to 21 July, britishmuseum.org

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion