Joseph Lelyveld's book Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India does not break new ground, but the Gandhi of hagiographers takes a beating. We get reaffirmation, however, of Gandhi's sheer presence, persistence and self-creation through self-promotion.

What gets confirmed, too, is the moral ambiguity of the man who many people still revere as a saint. Men such as Aurobindo, who similarly launched their political and public careers in India, wisely took to the hills to contemplate life and the afterlife and provided a much more nuanced understanding of the Hindu/Indian spiritual ethos. But Gandhi was too mesmerised by himself, despite his oft-repeated protestations that he was not a visionary and that he was "prone to many weaknesses". That is both the gall and the honesty of the man: while he acknowledged that he was frail and vain like any other man, he got away with idiosyncrasies, foolish projects, unilateral decisions and political manipulation that allowed him to exercise enormous power and influence circumventing democratic processes.

Lelyveld's book, because of the revelations about the relationship that Gandhi had with the German architect Hermann Kallenbach, has already been banned in Gandhi's home state of Gujarat. In an attempt to outdo the chief minister of Gujarat, the law minister of India contemplated writing into the books a law that would make "insulting" the Mahatma an act of blasphemy. India, it seems, is finally catching up to its neighbour's uses for blasphemy.

For most Indians, the tale of the Mahatma is limited to the expurgated version of The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Some might have chanced upon Erik Erikson's Gandhi's Truth, but one rarely heard a conversation at home or in school about Gandhi's moral dilemmas as well as the aberrant and sometimes cruel behaviour that drove one of his sons to alcohol and some of his staff to quit in disgust. Even now, much of the political discourse in India has to do with charges against the "Hindu brigade" – for allegedly abetting and/or plotting Gandhi's assassination. The Hindu brigade, overcompensating for their provincialism and feelings of guilt, have included Gandhi in their overly long salutation to Indian greats in the Ek Mata Stotra (their unity hymn).

In all this we ignore the fact that many people quarrelled with Gandhi. Many were troubled by his idiosyncratic ways, which we now know included sexually aberrant behaviour. It was not just the Hindu brigade that quarrelled with him but so did Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Annie Besant, Aurobindo, Ambedkar and others. Besant told Durga Das, a well-known and influential journalist, that she thought Gandhi was leading the country to anarchy.

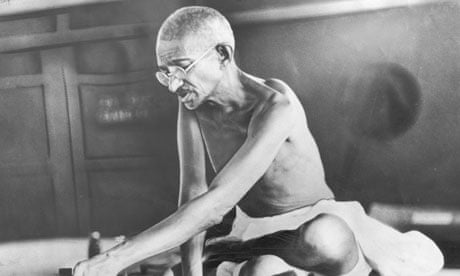

Gandhi's peccadilloes and idiosyncrasies drove quite a few people up the wall. He was considered by many to be a "difficult person," as he insisted that those around him and the people of India follow him in his peculiar "ascetic" ways. Alas, very few people knew about his dangerous experiments to test his willpower and ability to withstand sexual temptation. One of those "experiments" included sleeping naked with his teenage grand-nieces, Manu and Abha.

Some of the tests of will were neither new nor strange in some of the esoteric ascetic and spiritual traditions of India. But such practices were usually taught and carefully monitored by teachers, and were barred to those in the secular world. Because he was assassinated, we now ignore the frailties and the follies of the Mahatma. What is unremarked in many of the renderings on Gandhi is that his understanding of individual growth ignored the traditional Hindu version that sought balance between the four stages of life – brahmacharya, grihastya, vanaprastha, and sannyasa, and the four concerns of Hindus – dharma, artha, kama and moksha. Gandhi's transition from the medieval to the modern without the understanding of the ancient led to his incomplete view of Indian history, culture and mores.

Gandhi defined satya (truth) and ahimsa (non-violence) as positivistic and absolutist respectively. In his autobiography, factual and ethical truth is equated with ultimate truth. But in the practice of ahimsa, a mystical force of non-violence is presumed to be experienced as ultimate truth that can bring about a change of heart in the opponent. In other words, his practice of truth or transparent right conduct acquires the mystical power of saving oneself and others. This is the medieval Vaishnava practice where surrender through right conduct "saves" the devotee. But as a political doctrine this approach did not always deliver the change of heart in the opponent. Thus, we observe Gandhi's disappointing engagement not only with Muslims, Christians, the British and the communists, but also with many Hindus too.

Lelyveld's book, with a very small dose of titillating material about the Great Soul, therefore elicits howls of protests from those who have ensconced him among the pantheon of Hindu mythic figures. Unless we understand why Gandhi evoked mixed feelings, we will continue to deify him or lock away his many aberrations in the Indian family closet.