Nick Park, creator

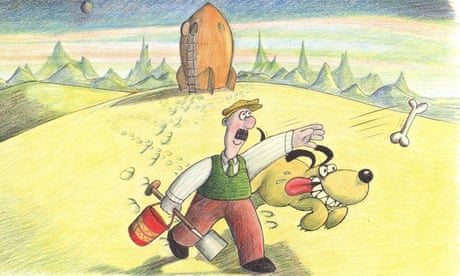

As soon as I started filming A Grand Day Out, the first Wallace and Gromit animation, I realised I was making a film about my dad. He loved tinkering about in the shed. He didn't look like Wallace, but somehow I could see him in his eyes – although my dad's eyes didn't meet in the middle, of course.

It was 1982 and, back then, Wallace had no eyebrows, hardly any cheeks and a moustache. And Gromit was embarrassing: he had a nose like a banana, or a cross between a banana and a pear. When Peter Sallis, who voices Wallace, said "No cheeeese, Gromit" for the first time, I realised how wide and toothy I was going to have to make Wallace's mouth.

I got the word gromit off my brother, who was an electrician. A grommet is a rubber thing used to insulate wiring. I liked it so adopted it. And at one point, Wallace was called Gerry, but I really liked how Wallace sounded with Gromit. He was actually a cat in my earliest sketches! But it's easier to make a dog with clay: you can roll it into larger sausages. He was going to have a mouth and do a lot of growling, but I soon saw how hard that was, so I started tweaking his eyebrows instead – and that did everything. With clay, you can create character out of tiny nuances. Gromit was born out of clay, really. If he'd been designed by computer, I'd never have arrived at him. One country, I think it was Finland, dubbed him. They actually gave him a voice – like he was lacking one!

Wallace only loves cheese because I wasn't au fait with scriptwriting as a student. I just started off with a guy building a rocket in his basement. Then I thought he needs someone to talk to and a reason to go to the moon – and the only thing I could come up with was him believing it's made of cheese. The first script would've made a four-hour film. At one point, there was a moon McDonald's that served banana milkshakes. It was going to be like that Star Wars scene with all the aliens in the bar. When Aardman took me on, their first advice was how to cut something down so that it's makeable in four years. A Grand Day Out took me seven in total.

I had a number of ideas kicking around for The Wrong Trousers, which followed in 1993. One was this pair of techno trousers that allowed Wallace to walk up walls; another was the penguin lodger, Feathers McGraw. Peter Lord, Aardman's founder, said to me: "What if he was a villain?" And it suddenly became a Hitchcock thriller, with a bit of "Put a rubber glove on your head and you're a chicken" humour, too.

The train chase is something I'd never seen done before in stopframe animation. None of us knew how to do it – or even if it could work. In Tom and Jerry chases, you used to get the background whizzing by and repeating itself, so we tried the same. We built a 20ft long living room wall, 2ft high, and fixed the camera to the train, and filmed on a long shutter speed so the background looked blurry. It was quite a feat.

The Wrong Trousers had two or three animators, and we'd be off setting up another set while one was being shot. Later, on our bigger feature films, we'd shoot over 18 months, with 25 to 30 animators and a crew of up to 300 shooting on 25 sets at once. As director, I like to act each scene through first, so I can check the looks, speed or impact I'm after.

We made The Curse of the Were-Rabbit with Dreamworks, and it was often a struggle to keep things as we wanted. They'd say: "Why do they have to have an Austin A35? Can't they have a pickup truck or something cool?" But I love it because it's not cool. We were going to call it The Great Vegetable Plot, but research showed that vegetables were a negative with American kids, and they didn't know a plot is a place where you plant vegetables.

Some things lend themselves to spinoffs. We've often been asked where Feathers McGraw is now and if he ever got out of jail. We've also thought about Wallace and Gromit's backstory. I imagine they were both babies at the same time – a baby and a puppy – so we've been exploring that. A prequel isn't what's next for them, though.

Digital animation is getting better all the time – they can make it look so much like clay now – but for me, there will always be a difference.

Peter Lord, Aardman co-founder

Nick was the only other person in the world, as far as we know, who was working in Plasticine. He was the obvious guy for us to take on at Aardman – even before we saw what he was doing. He was still at the National Film and Television School when we first met. When he showed us Wallace delivering a line of dialogue – "We've forgotten the crackers!" – we laughed out loud. That's extremely rare and it's not even a joke. But the sight of him was so funny. We knew he had a good thing going.

I've sometimes had to put my foot down – usually over length and overelaboration. If I hadn't, A Close Shave would have been 50 minutes long, rather than 30, and that's an awkward length. In fact, A Close Shave contains the best scene we ever had to cut. Its love story, between Wallace and Wendolene, was based on Brief Encounter and that very English embarrassment about expressing your feelings. At one point, there was a big love scene set in Crewe railway station. It's always painful but sometimes you have to throw away ideas.

Nick manages to convey in animation what Wallace and Gromit are thinking – and that's something most animators can't do. The lack of sentiment is the most charming thing about them: their affection is never saccharine, never obvious, just kind of real. I love their Jeeves and Wooster thing: the master being such a dope and failing to properly value his lower-status companion – I won't say servant – who is so much more intelligent.

Nick's so good at invention. He takes a simple idea and adds all these surprises. I watched A Close Shave the other day and I'd forgotten how funny the big showdown in the mill is, with all the sheep about to get turned into dogfood. There they are in the middle of this terrible scene with this monster robot dog, this people-crushing machine, and Gromit and Shaun the Sheep are doing their best. Then good old Wallace tries to help, but presses the button that almost tips him and all the sheep straight into the dogfood machine.

Not helping – that's Wallace's great trait. Right from the start, we could see how memorable the two of them could be.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion