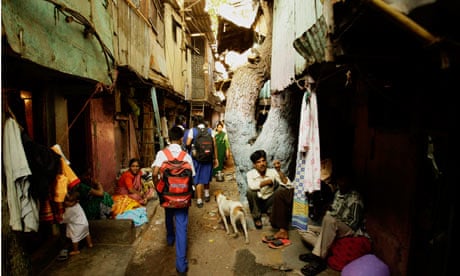

Ninety Feet Road runs through the middle of Dharavi, the area in the centre of Mumbai notorious for being southern Asia's largest slum. The street's name comes from its width – it is the broadest thoroughfare among the congested mass of homes, tenements, workshops and alleyways made famous by the Oscar-winning film Slumdog Millionaire.

It has seen many battles, but few as acrimonious as this most recent fight: to claim the credit, money, power and votes that will come from levelling much of the neighbourhood in a multibillion-pound slum clearance programme.

The battle is heating up with the approach of civic elections in India's commercial capital in under a year. At stake is not just the future of Dharavi, but also lucrative building contracts and the survival as a mainstream force in Mumbai of the Shiv Sena, the radical rightwing party that has dominated the streets of the city for nearly 50 years. Poverty, vast sums of money and cutthroat slum politics are combining into an explosive mix.

Wedged into two square kilometres in the centre of Mumbai, Dharavi is home to somewhere between 250,000 and a million people, depending on the season and the estimate. For more than a decade, city authorities have debated razing Dharavi's largely illegal tenements, shacks and squats and rehousing the population in high-rise blocks with power, water and sanitation. Currently only one in 1,000 local residents has access to a toilet and the area is prone to flooding and disease.

Fire is a continual hazard, as was made clear this weekend when flames tore through a nearby slum and made around 2,000 people homeless, including Rubina Ali, one of the young stars of Slumdog Millionaire.

Tens of thousands arrive or are born in Dharavi each year. But progress on the ambitious clearance project, one of the biggest ever attempted, has been blocked by the competing demands of different interest groups – and the fear that the only people who will profit are builders, corrupt politicians and the extremists.

Chief among the latter are the Shiv Sena – the name means "warriors of Shivaji", a former ruler of the region. Their tactics in Dharavi are simple. Having originally launched the redevelopment plan when in power in the late 1990s, the Sena are now seeking to block it unless residents are guaranteed homes with a living space of at least 37 sq metres (400 sq ft), almost twice that foreseen in the original designs. Ageing leadership and splits have sapped support for the party over recent years. Fighting for the rights of slum-dwellers – particularly on the issue of living space, which touches almost all Mumbai's 15 million inhabitants – is seen as a certain vote-winner.

"We are seeking justice for the poor of Dharavi. We are burying all our differences of region and community," Baburao Mane, a former Sena member of the local parliament and one of the harshest critics of the development plan, told the Observer.

Yet the Sena face an uphill struggle. Around a third of Dharavi's residents are Muslims; another third are migrants from India's interior and poorer north. Both have been targets of Shiv Sena's rhetoric – and worse – for decades and are hardly natural supporters of the extremist group, which was founded in 1966 to fight for the rights of people born and bred locally.

Twenty years ago, Mane himself led meetings that helped to spark riots in which 900 died. Now, the politician and headteacher claims, he and the Sena "have repented of all that". "We preach harmony. We teach four different languages in the school I run and we all worship together," Mane, 58, insisted.

However, there is evidence that the old instincts of the Shiv Sena remain. Last year the party, following orders from its veteran leader and founder, Bal Thackeray, tried to stop the showing of a blockbuster movie because its star had made comments favourable to Pakistani cricketers. In October, Thackeray's grandson forced a local university to remove a supposedly anti-Mumbai and anti-Indian book by respected Indian-born author Rohinton Mistry from reading lists. Last month, the party threatened to disrupt the cricket World Cup final, scheduled at Mumbai's Wankhede stadium for 2 April, if it involved Pakistan playing India. Such trademark populism has now been extended to Dharavi, critics say.

"The redevelopment plan has become very politicised," said Raju Korde, a lawyer who heads a group of local activists.

However according to Korde, who grew up in a tiny house in Dharavi, the real issue is elsewhere. Few politicians, he said, speak much about the most sensitive issue: the money private builders will make from the redevelopment.

The sums involved are colossal. With India's economic growth hitting almost 9% year on year, property prices in Mumbai, India's richest city, are among the highest in the world and the two sq kilometres of Dharavi represent a goldmine. One Mumbai newspaper last week called the redevelopment plan a "jackpot" and quoted gleeful officials claiming that £3bn that could be generated for the municipality. The profits for the major construction firms that look certain to win contracts for the work, however, could top £8bn.

Local campaigners argue that the builders, who will not have to pay for the land, should be allowed to sell only a third of the homes they build. The authorities say the proportion should be well over half.

According to Korde, the authorities' current resistance to the 37 sq metres demand – which he and other lobbyists formulated after extensive legal research – is rooted in the desire of senior politicians and bureaucrats to allow the builders to construct a larger number of smaller homes. This, he claims, would earn them much more money. "There is not a member of the local assembly who is not linked to a construction firm," Korde said. "They can make tens of millions. The more flats there are the more they make."

Historically, even small development projects in India have generated huge amounts of corruption as constructors compete to pay off officials and politicians, and politicians work to be in a position to make crucial and lucrative decisions. Land all over India has become a major driver of graft, with the unprecedented funds generated contaminating the electoral and legal processes on a massive scale. Without the prospect of material gain, the demand for units of 37 sq metres would have been granted long ago and the campaign of the Shiv Sena would have become irrelevant.

Instead, there are signs that the extremists are making headway. Along with the Shiv Sena, a splinter group is also doing well in Dharavi. The Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) has already attracted younger, and often educated and affluent, local-born Hindus since being set up five years ago. The MNS also backs the 37 sq metres demand. "There can be no compromise on that," said Ganesh Khade, an organiser for the group. "I already live in somewhere bigger than the units the government are offering, so why would I accept less?"

Whatever the eventual decision, priority has to be given to longer-term residents of the neighbourhood, Khade insisted, as "there are already too many immigrants in Mumbai in general and in Dharavi in particular".

Krishna, a 44-year-old house painter who lives with his family in a 4.5 sq metre room in Dharavi, said he had recently switched his allegiance to the extremists. His home was built by the grandparents of his wife, who hawks snacks on Mumbai's railways. "I'm sick of the promises the other parties always make," he told the Observer. "We need someone with clear ideas who can make a change. The Shiv Sena gets things done."

Last week, Prithviraj Chavan, the chief minister of Maharashtra state, announced that work on redeveloping Dharavi would start within months. Any decisions would be taken with the slum dwellers' interests "first and foremost", officials maintained.

"I'll believe it when I see it," Krishna the painter said. With so much cash, power and votes at stake, no one expects the battle over Dharavi and its redevelopment to end soon.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion