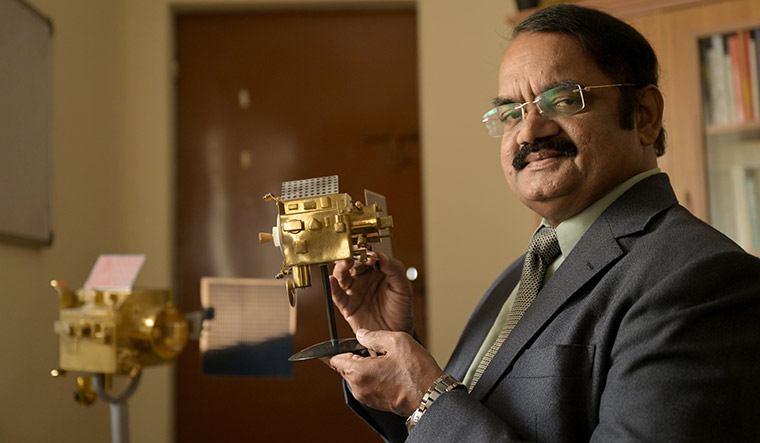

He is not called the ‘Moon Man of India’ for nothing. Mylswamy Annadurai played a pivotal role in developing the spacecraft for Chandrayaan-1, India’s first lunar mission. A Padma Shri awardee, he was the programme director of not just Chandrayaan-1, but also Chandrayaan-2 and the Mars Orbiter Mission. He was with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) for 36 years and was also the director of the U.R. Rao Satellite Centre in Bengaluru. In an exclusive interview, he tells THE WEEK about the challenges associated with lunar missions and why India needs to further improve its launch capabilities. Excerpts:

Q Can India look forward to a manned mission to the moon?

A When Chandrayaan-1 was launched, we had a very modest launch vehicle―the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). When you compare it with Russia or the United States, they have superior launch capabilities, as they can push the spacecraft towards the planetary body with one shot. We do not have such powerful launch vehicles even today. The Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV), too, does not have the capability to put the spacecraft directly towards the planetary body. India can further improve its launch capabilities.

Today, we are talking about the human spaceflight (Gaganyaan) mission, which will take astronauts to the low earth orbit and then return. Since it is the low earth orbit, the present human-rated GSLV (LVM3) will be more than enough to take them there. But in case India needs to send a man to the moon in the future, we cannot take the route that we have taken now. In the present mode, we have designed only the landing, whereas in human lunar mis sions, a person has to come back as well. For the return, one needs to have a more powerful propulsion system and lander, and the vehicle will weigh more as it will require as much fuel to return safely. That means the GSLV will require twice its current power. Today, we have just carried a lander and rover, but if we have to carry two or three people and their support system to the moon, it will not be possible with the current launch capabilities.

Q What can be done to improve the situation?

A One option is that we need to make our launch vehicles bigger and more powerful. Another option is to collaborate with international agencies and use their launch vehicles to send our spacecraft. Post that, we can gradually improve our launch capabilities.

Q What are the challenges associated with a lunar soft landing?

A With Chandrayaan-3, we are targeting a place in the south pole where it has to land with minimal velocity―around 1m or 2m per second. To start with, it will have 1km per second velocity when it is orbiting the moon. When you reduce that velocity, it will naturally keep falling. When it falls, it will pick up velocity. One has to manipulate the lander in such a way that it reduces both the horizontal and the vertical velocity. This calls for very close manoeuvers. So it has to be ensured that the lander does not hit the ground very hard and the velocity has to be zero. At the same time, it needs to be ensured that one or two legs of the lander do not land on a stone. It also calls for another manoeuvre―to move laterally, left or right. The challenge is that the time available is very less.

Q How challenging is it to coordinate with other teams?

A When we developed Chandrayaan-1, it was really challenging to develop the spacecraft as there were many foreign instruments to be taken within the spacecraft. We had to ensure that the spacecraft, including the instruments, did not weigh more than 500kg. It took us around four years (2004-2008) to develop the Chandrayaan-1 mission. My team was very cooperative. G. Madhavan Nair, who was then ISRO chairman, gave me a free hand to select the team. Our team also had scientists from different labs of NASA. I had to put in almost 13 hours daily to develop the Chandrayaan-1 satellite at the U.R. Rao Satellite Centre. During my stint with ISRO, I had the chance to work on more than 60 satellites.

Also read

- Why Vikram lander, Pragyan rover remain dormant despite best efforts to reactivate them?

- Chandrayaan-3: Rover confirms presence of Sulfur in lunar surface; search on for Hydrogen

- Chandrayaan-3 updates: Pragyan rover comes across large crater on its way; changes path

- Chandrayaan-3 has been about making the most of available resources

- How India learnt its lessons from Chandrayaan-2 debacle

- Importance of space exploration for life on earth

Q Did you get free time during the missions?

A As project and mission director, you do not get much spare time to pursue personal hobbies and interests. One has to work very meticulously, as team members will have some issue or the other during the mission. Though a lot of travel was required to coordinate between different centres, I tried to cut down on that by having regular video conferencing sessions and online meetings from 2004 itself. I encouraged that mode and everyone got used to it. At times, I used to get the satellite data to my house and work on it there, too.

Q How many people work on a mission?

A It depends. We need to identify the overall job at first. After that, we need to arrive at the configuration of the satellite, depending on what the launch vehicle and the satellite can do. To start with, there will not be more than 50 to 60 people to develop an initial design. Once the design is finalised, we reach out to various centres to develop the design. Post that, the team expands to 400 to 500 people and then keeps on increasing. The teams then get involved in testing and integration. Initially, ISRO used to work on a single mission, but now there are multiple launches, requiring the involvement of private firms, too.