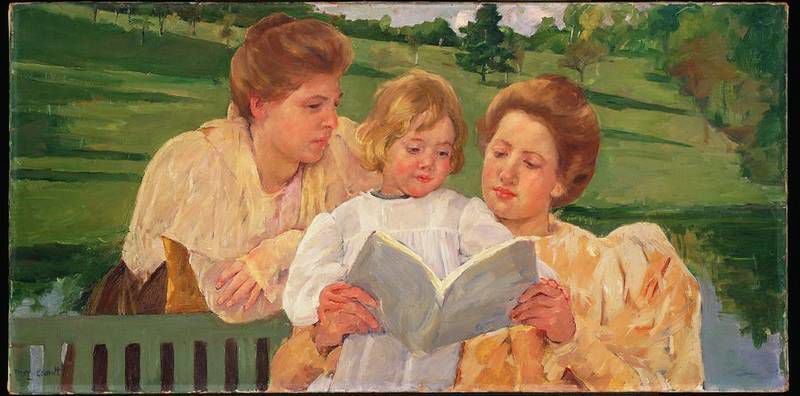

For centuries, the Madonna and child was one of the primary subjects of Western painting. Nearly every Italian Renaissance painter and Dutch master from Bellini to Van Eyck immortalized this fundamental miracle of Christianity the virgin birth of God's only son. In the 19th century, Mary Cassatt was the first painter to see the relationship between an ordinary mother and her child as no less miraculous. She depicted the daily routine of maternal care mothers bathing toddlers and babies, coaxing grumpy tots from the brink of tears, reading to bored older children with the same kind of reverence the old masters painted the holy mother and baby Jesus. Cassatt did so though in an entirely different style. Cassatt was an Impressionist, the only American-born painter among a group of French rebels who broke away from the academy to experiment with the use of natural light, painting en plein air and depicting real subjects in the contemporary world. Cassatt also happens to be the one of most important women artists of the modern era. Her work is in prominent international museum collections, and it is also among the Impressionist works on permanent display at the Shelburne Museum. This summer, the museum is hosting a blockbuster show of more than 60 works by Cassatt and Degas from its own collection and from works on loan from private collectors and museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The exhibit, "Mary Cassatt: Friends and Family," highlights the 50-year relationship between the artist and Louisine Elder Havemeyer, and the impact their friendship had on the American embrace of the Impressionist movement. The exhibit includes some of Cassatt's seminal works, namely the aquatint "Maternal Caress" and the oil painting "Bathing the Young Heir." In all, there are eight small pencil drawings, seven pastels, 13 oils and 28 prints; a number of these works are little-known family portraits from private collections. The exhibition also includes nine works by Degas, Claude Monet's painting, "Le Pont, Amsterdam," and the translated correspondence of Cassatt and Havemeyer. Cassatt developed a friendship with Louisine Elder early in her career. An inveterate collector, Elder, began to build her collection from the age of 16, and in her 20s bought Impressionist paintings by Degas, Monet, Pissarro and Whistler on Cassatt's advice. Later, when Elder married H.O. Havemeyer, who consolidated the 16 sugar factories that became Domino sugar, she broadened her Impressionist collection substantially. Through their long-distance friendship Cassatt moved to Paris at 21 and never left, Havemeyer was ensconced in Manhattan with her husband and three children the two women brought Impressionist art to the United States before it was considered important in Europe. Havemeyer, who treated her Manhattan house like a de facto museum, opened her home to viewers. She held events and public hours to further popularize Impressionist works. After her death in 1929, Louisine's collection of 1,927 works of art was donated to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. A number of the paintings and sculptures were also passed down to her three children. The youngest of the siblings, Electra Havemeyer Webb, not only inherited a share of her mother's collection of paintings, but also her passion for collecting. In 1947, Webb founded the Shelburne Museum, one of the finest collections of American folk art in the world. Situated on 45 acres in the town of Shelburne, it includes 150,000 objects, 39 exhibit buildings (25 of which are historic masterpieces of vernacular architecture) with 132,000 square feet of exhibit space. Today, her mother's Impressionist and American art is on display in the Electra Havemeyer Web Memorial Building. The Shelburne Museum has been entertaining the idea of hosting Cassatt show for some time. (As executive director Stefan Jost puts it: "It's been in the air for about 10 years.") Clearly, it was worth the wait. Many of the works on loan are from private collectors, including the descendents of Cassatt, and are rarely on public display. After the exhibition closes at the Shelburne, it will travel to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. The Shelburne Museum has produced a color exhibition catalog featuring essays by Cassatt scholar Jay E. Cantor and by Nancy Mowll Mathews, the Eugenie Prendergast Senior Curator of 19th and 20th Century Art and Lecturer in Art at Williams College Museum of Art, who has written several books about Cassatt. T The artist's life story is one of privilege, vision and determination. Cassatt was born to a prominent Pittsburgh family in 1844 and went on an extended stay in Europe with her parents for the first time when she was only 6 years old. When her family settled in Philadelphia shortly afterward, she had already decided to become an artist. At 16, she gained entrance to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and just five years later she left to study in Paris. Her subject, from the beginning, was the human figure. She began to exhibit work at the Paris Salon in the 1870s, but broke with the academy to pursue Impressionist techniques by the end of that decade. Though she never married or bore children herself, Cassatt dedicated the next 20 years of her life to re-creating intimate family scenes. Many of the portraits on display at the Shelburne Museum are of her friends and relatives participating in the private activities of family life: bathing, drinking tea, reading books or merely leaning on one another and staring into space. Cassatt depicts these loved ones with a raw intensity. The mothers cradling or nursing their babies seem transfixed by their own infatuation with the infants. Their mother love, is often all-encompassing in Cassatt's paintings, prints and drawings. Their faces are fused together in a kiss or an embrace, or their bodies become one amorphous form. Cassatt's paintings visually articulate the emotional states of motherhood and childhood. The psychological attachment is real and manifests itself in a physical way. That isn't to say, however, that Cassatt sugarcoats the maternal relationship. The figures aren't idealized. The mothers are at the edge of patience; the children often look peeved or bored, and even the babies are disgruntled. Occasionally, though, as in the exquisite portrait of Electra and Louisine Havemeyer, Cassatt captures a magical harmony. In "Augusta Reading to Her Daughter," mother and child look as though they are thoroughly fed up with each other, even though the girl is leaning on her mother's lap. The daughter's pink gown glows in garish contrast with Augusta's green dress. They are sitting on a bench outside in a lush, verdant setting. A pond behind them reflects a woodland. In spite of the idyllic landscape, their expressions belie an unhappy subtext, perhaps an essential impatience with each other. "Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror)" on the other hand illustrates a scene that could be taken straight from a Renaissance depiction of the Madonna and child. The tot in Cassatt's painting is a young male god whose mother seems to drawn to worship. Cassatt's clarity of insight into her subjects is softened by her broad open brush strokes. In many of the works, she details the facial expressions of her subjects and then lets the bodies melt away in undefined lines. These monumental mother-and-child works have broad appeal, probably because Cassatt has visually defined the nature of unconditional love, the familial devotion most evident in small tangible offerings.

Mary Cassatt: Friends and Family

Blockbuster exhibit reveals relationship between America's Impressionist and the Shelburne Museum

- By Anne Galloway Times Argus Staff

- Updated