How Robert Frank's Book The Americans Redefined American Photography

Few photographers have managed to capture the American life and culture as honestly as Robert Frank. Described as the most influential photo book of all times, his seminal series The Americans earned him comparisons to a modern-day de Tocqueville for his fresh and nuanced outsider’s view of the post-war American society. Created in the 1950s during a series of road trips through the United States, it showed a different America as opposed to the country’s self-image at the time. While capturing highways, parades, cars, diners, jukeboxes and many other American symbols, Frank portrayed an underlying sense of alienation and hardship. He investigated the gaudy insanities and strangely touching contradictions of American culture, presenting a basis for a coherent iconography of the time. His book redefined what a photobook could be - personal, poetic, and real - ultimately changing the course of the twentieth-century photography.

After almost sixty years, this body of work remains as powerful and provocative. Selected works from this seminal series will soon be on view at Albertina. Simply titled Robert Frank, the exhibition will show selected groups of artworks that make it possible to retrace the photographer’s development as an artist: from his early travel photos to The Americans and onto his introspective late oeuvre, central aspects of his oeuvre are placed front and center.

On the Road - Robert Frank and The Americans

Born in Zurich in 1924, Robert Frank came to New York in 1947, eager to escape his father’s radio-importing business. He earned his living as a commercial photographer, spending his time off wandering New York and photographing what he found. In 1954, he applied for a Guggenheim fellowship with references written by Walker Evans and Edward Steichen, proposing to create “an observation and record of what one naturalized American finds to see in the United States." With an aim to photograph America as it unfolded before his eyes, he set out to do something new and unconstrained by commercial diktats, creating a now classic book characterized by the iconoclastic spirit.

In a newly bought Ford, Frank went on three separate road trips across America over the course of two years, for the most time accompanied by his wife and two young children. Photographing American society and all its strata, he used 767 rolls of film and created 28,000 shots. His first stops were in Pennsylvania and Ohio, then Michigan, where he was allowed to photograph inside Ford's River Rouge plant in Dearborn. Yet, his journey wasn’t without incidents. He has spent three days in jail an Arkansas on the accusation of being a communist spy in the midst of the Cold War and a sheriff elsewhere in the South told him he had an hour to leave town.[1]

Scratching Beneath the Surface

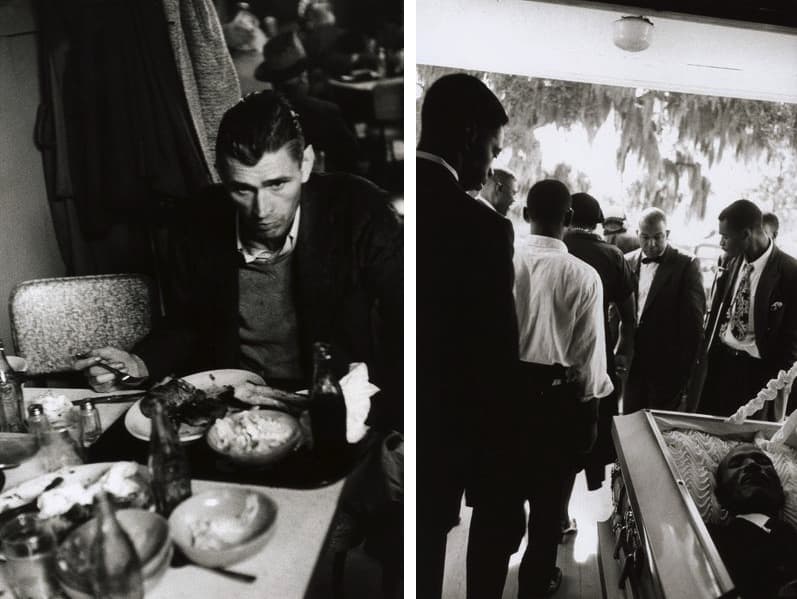

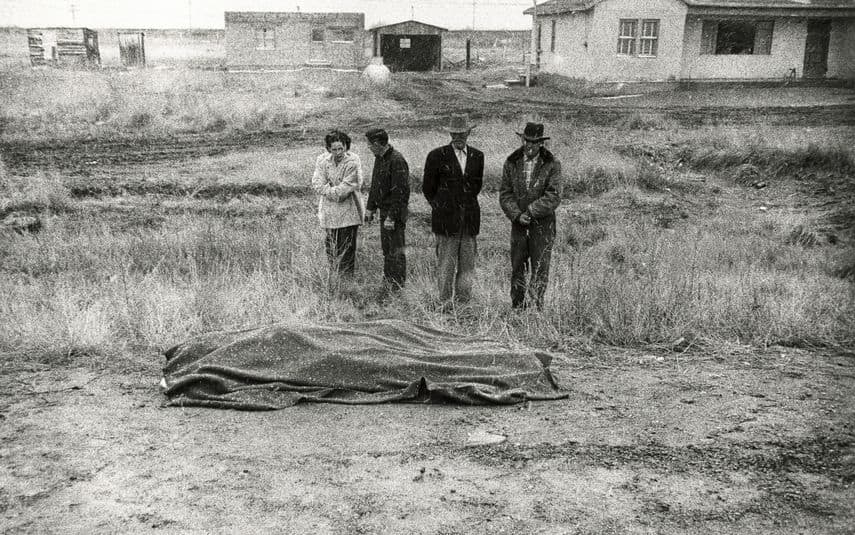

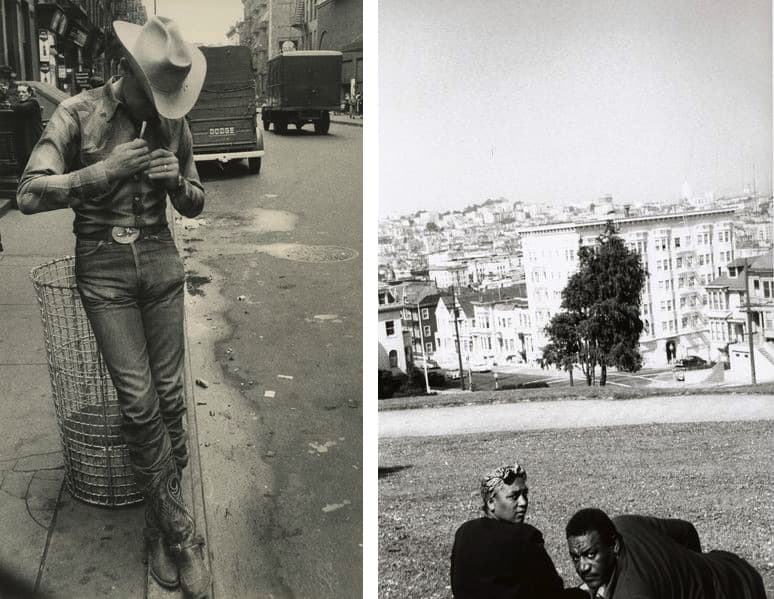

Robert Frank’s book dramatically altered how photographers looked through their viewfinders and the way Americans saw themselves. His subjects weren’t necessarily living the American dream of the 1950s. They were factory workers in Detroit, transvestites in New York, black passengers on a segregated trolley in New Orleans, a cowboy pausing to roll a cigarette in midtown Manhattan, a man in front of the jukebox with an empty dance floor behind him. Frank rarely spoke to his subjects; he chose to point, shoot and move along. Cruising around luncheonettes, public parks, roadside bars, and factories, he captured ordinary people doing ordinary things.

There were no beauty spots in his images - he photographed cars, diners, postcard racks, gas stations, drug stores, hotel lobbies, strip developments, empty spaces and unknowable faces as telling symbols of contemporary life. His shots were not artfully framed or carefully balanced, breaking the conventions of acceptable photojournalism. He shot seemingly loose, casual compositions, with often rough, blurred, out-of-focus foregrounds and tilted horizons.

Looking beneath the surface of American life, he revealed a profound sense of alienation, angst, and loneliness. Simply showing thing as they were, he illuminated the postwar American way of life in grim black and white and captured the gap between the American dream and everyday life. He found tension in the gloss of American culture and wealth over race and class differences, revealing reality of prevailing racism, violence, and consumer culture. He showed a sad, hard, divided country that seemed essentially melancholic.[2]

When it comes to editing his own images, Robert Frank was meticulously ordered and rigorous. He edited 27,000 of them down to about 1,000 prints, spread them across the floor of his studio and tacked them to the walls for a final edit. Out of a year and a half of work, Frank chose just 83 photos. The selection of photos and their sequence and pacing is fresh, rich, generous, and stunning. One can sense the narrative thrust that underpinned his thinking about the book and about photography in general.

Constructed in four sections, each begins with a picture of an American flag and proceeds with a rhythm based on the interplay between motion and stasis, presence and absence of people. Using thematic, formal, conceptual and linguistic devices to link the photographs, he created a book that displays a deliberate structure, an emphatic narrator, and distinct and intense order.

The Cold Reception

Shortly after returning to New York in 1957, Robert Frank met the writer Jack Kerouac on the sidewalks outside a party and showed him the photographs from his road trips. Kerouac immediately agreed to write an essay about the works. Published as an introduction to the first American edition, that was released a year after the French one, Kerouac’s text is a perfect complement to the photographs. The famous Beat writer wrote:

Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps, and with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America on to film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.[3]

Yet, the pictures took the public and contemporary critics by ambush, who reacted with a mixture of scorn and outrage. The Americans defied the country’s self-image at the time, showing a place that many did not want to see. The book received harsh criticism in the USA, where it was perceived as derogatory to national ideals. The support from the art world was lacking.

Minor White, the renowned photographer and Aperture magazine editor called it "a wart-covered picture of America by a joyless man". The magazine Popular Photography described it as "a sad poem by a very sick person" and derided Frank’s images as "meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness". As Frank recalls, not even MoMA would sell the book and it quickly went out of print after selling 1,100 copies.[4]

Yet, Kerouac’s introduction did help it reach a larger audience due to the popularity of the Beat phenomenon. Over time, the book and its author have gained the long-deserved recognition and praise.

A Lasting Legacy

No other book had an influence on the course of contemporary photography as The Americans did. It has challenged the documentary tradition, where photography was understood as something transparent and simplistic that was not informed by thoughts, emotions or viewpoints of the photographer. Robert Frank rebelled against the popular 1950s notion that photography was a universal language, easily understood by all, aiming to create an ambiguous form that engages the viewer and leaves them with as many questions as answers. Experimenting with composition, blur, exposure and grain, he has also challenged the aesthetic of photography that championed technical perfection in terms of clean, well-exposed, and sharp photographs.[5]

With the formal iconoclasm and a defiantly unromantic gaze, Frank influenced just about every street photographer that followed. "Seeing The Americans in a college bookshop was a stunning, ground-trembling experience for me," the photographer Ed Ruscha once recalled.[6]

But I realized this man’s achievement could not be mined or imitated in any way, because he had already done it, sewn it up and gone home. What I was left with was the vapors of his talent. I had to make my own kind of art. But wow! The Americans!

Joel Meyerowitz, a pioneer of color photography and a legend in his own right, was also deeply affected by this body of work:[7]

It was the vision that emanated from the book that led not only me, but my whole generation of photographers out into the American landscape in a sense — the lunatic sublime of America.

When discussing the photograph Canal Street, New Orleans, Meyerowitz recalls he was first puzzled with this image, wondering why Frank decided to shoot this undifferentiated mass of pedestrians. He explained:[8]

Over time, I came to realize that the reasons for making a photograph and what it may mean to you later are two different things, and what it means to somebody else is yet another. This image came to life for me years after I first puzzled about it, when I was undertaking a transformation in my own work and realized that Robert had planted a seed that was then sprouting.

With such a powerful impact, The Americans is probably the one book that connects more photographers than any other.

Seeing the series as social analysis, the sociologist Howard S. Becker was the one to compare Frank’s book with de Tocqueville's analysis of American institutions and of the analysis of cultural themes by Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. He wrote:[9]

Frank presents photographs made in scattered places around the country, returning again and again to such themes as the flag, the automobile, race, restaurants - eventually turning those artifacts, by the weight of the associations in which he embeds them, into profound and meaningful symbols of American culture.

The Man Who Saw America

In a 2004 interview with The Guardian, Robert Frank asserted that the kind of photography he did was gone, it was old. He noted:[10]

There are too many pictures now. It’s overwhelming. A flood of images that passes by, and says, 'why should we remember anything?' There is too much to remember now, too much to take in.

Yet, it would be difficult to imagine the past and present of photography without the acuteness of his eye. He has an outstanding ability "to invest the seemingly commonplace with supplementary qualities, romantic or religious and always mysterious". This man, who saw America as it was brought the cold, hard truth of his outsider’s gaze, establishing its new iconography. At the same time, he changed the very nature of photography, what it could say and how it could say it. With The Americans, Robert Frank did ultimately succeed in creating one of the most influential photographic works of the post-war period while also effecting a sustained renewal of street photography.

The exhibition Robert Frank will be on view at Albertina in Vienna from October 25th, 2017 until January 21st, 2018. The guided tour in German by the curator Dr. Walter Moser will be organized on December 13th, 2017, from 5:30 p.m.

Editors’ Tip: Looking In: Robert Frank's The Americans: Expanded Edition by Sarah Greenberg

First published in France in 1958, then in the United States in 1959, The Americans changed the course of twentieth-century photography. Drawing on newly examined archival sources, the book provides a fascinating in-depth examination of the making of the photographs and the book's construction, using vintage contact sheets, work prints and letters that literally chart Frank's journey around the country on a Guggenheim grant in 1955–56. It also explores the roots of The Americans in Frank's earlier books, which are abundantly illustrated here, and in books by photographers Walker Evans, Bill Brandt and others. The catalog concludes with an examination of Frank's later reinterpretations and deconstructions of The Americans, bringing full circle the history of this resounding entry in the annals of photography.

References:

- Cole, T. (2009) 'Americans': The Book That Changed Photography. NPR. [September 13, 2017]

- O’Hagan, S. (2009) Robert Frank’s The Americans Still Shocks, 50 Years On. The Guardian. [September 13, 2017]

- Frank, R. The Americans, from the introduction by Jack Kerouac. Steidl, 1959

- Riefe, J. (2015) The Americans: Robert Frank’s Legendary Photographs Head to Auction. The Guardian [September 13, 2017]

- Kim, E. Robert Frank’s “The Americans”: Timeless Lessons Street Photographers Can Learn Eric Kim Photography [September 13, 2017]

- Anonymous The Americans, Review Lens Culture [September 13, 2017]

- Cole, T. (2009) Ibid. [September 13, 2017]

- Anonymous (2017) Eight Photographers on Their Favorite Image from Robert Frank’s “The Americans”. The New Yorker [September 13, 2017]

- Becker, Howard S. Photography and Sociology. American Ethnography Quasimonthly, 2009

- O’Hagan, S. (2014) Robert Frank at 90: The Photographer Who Revealed America Won’t Look Back. The Guardian. [September 13, 2017]

Featured images: Robert Frank - 14th Street White Tower, New York, 1948 © Robert Frank, Fotostiftung Schweiz; Wellfleet, Massachusetts, 1962 © Robert Frank, Fotostiftung Schweiz; Rodeo, Detroit, 1955. The Albertina Museum, Vienna, on permanent loan from the Austrian Ludwig Foundation for Art and Science. Courtesy of Albertina.

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.