SARDAR VALLABHBHAI PATEL Balraj Krishna - Esamskriti.com

SARDAR VALLABHBHAI PATEL Balraj Krishna - Esamskriti.com

SARDAR VALLABHBHAI PATEL Balraj Krishna - Esamskriti.com

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

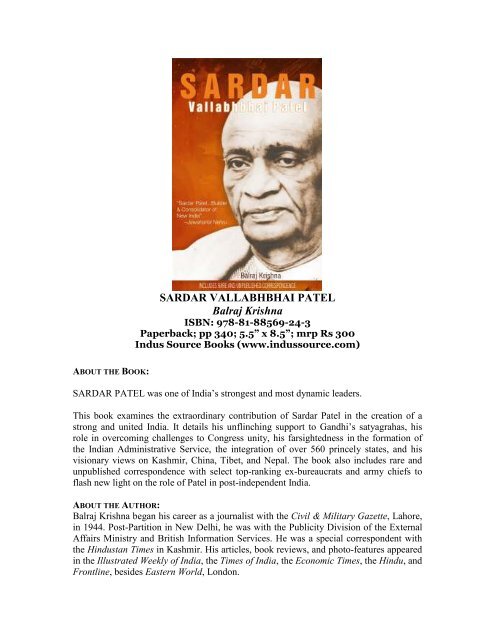

<strong>SARDAR</strong> <strong>VALLABHBHAI</strong> <strong>PATEL</strong><strong>Balraj</strong> <strong>Krishna</strong>ISBN: 978-81-88569-24-3Paperback; pp 340; 5.5” x 8.5”; mrp Rs 300Indus Source Books (www.indussource.<strong>com</strong>)ABOUT THE BOOK:<strong>SARDAR</strong> <strong>PATEL</strong> was one of India’s strongest and most dynamic leaders.This book examines the extraordinary contribution of Sardar Patel in the creation of astrong and united India. It details his unflinching support to Gandhi’s satyagrahas, hisrole in over<strong>com</strong>ing challenges to Congress unity, his farsightedness in the formation ofthe Indian Administrative Service, the integration of over 560 princely states, and hisvisionary views on Kashmir, China, Tibet, and Nepal. The book also includes rare andunpublished correspondence with select top-ranking ex-bureaucrats and army chiefs toflash new light on the role of Patel in post-independent India.ABOUT THE AUTHOR:<strong>Balraj</strong> <strong>Krishna</strong> began his career as a journalist with the Civil & Military Gazette, Lahore,in 1944. Post-Partition in New Delhi, he was with the Publicity Division of the ExternalAffairs Ministry and British Information Services. He was a special correspondent withthe Hindustan Times in Kashmir. His articles, book reviews, and photo-features appearedin the Illustrated Weekly of India, the Times of India, the Economic Times, the Hindu, andFrontline, besides Eastern World, London.

INTRODUCTIONPatel, along with Gandhi and Nehru, was a leading member of the triumvirate whichconducted the last phase of India’s freedom struggle. He was the “saviour” and the“builder”. Non-violently, he demolished the princely order Lord Wellesley had created;and in January 1946, he had nearly buried Pakistan in Karachi. Post-independence, Patelwas the creator of New India just as Surendranath Banerjea was the father of politicalconsciousness to the newly educated class of Indians in the 19 th century; and Gandhi, thefather of mass awakening pre-independence.(a) Saviour: Patel saved India from the machinations of the ruling British, and therebydid not allow large Hindu majority areas to fall into the hands of Jinnah. In 1946, in anundivided India, the Cabinet Mission was giving away to Jinnah a Pakistan <strong>com</strong>prisingthe whole of Punjab and Bengal, besides Hindu Assam, as fully autonomous parts ofGroups B and C. Gandhi favoured the plan since it preserved India’s unity. In his“paternal pride” as Congress president, Azad seemed totally <strong>com</strong>mitted, confident ofsecuring Congress acceptance. He thought that it would not only keep India united, butalso safeguard Muslim interests. Nehru, however, voiced his opposition to grouping, as itrelated to the NWFP and Assam. He even suggested that there was “a big probability”that “there will be no grouping”. Patel was more blunt than others in telling Wavell thatthe mission’s “proposed solution was ‘worse than Pakistan’, and he could not re<strong>com</strong>mendit to Congress”. 1India’s partition, as conceived by Churchill in 1945 as Britain’s prime minister, wasimplied in Attlee’s policy statement of 20 February 1947. It clearly meant the creation ofPakistan in one form or other, but in a divided India. Under it, too, Jinnah was to get thewhole of Punjab, Bengal, and Assam. Patel immediately countered it with a policystatement on behalf of the Congress, demanding a division of Punjab—and of Bengal byimplication—thereby saving Assam for India. Assam was predominantly Hindu, whereasin Bengal the Hindus were 49% as against 51% Muslims.(b) Builder: Attlee’s statement of 20 February categorically stated transference of powerto the princely states, simultaneously with India and Pakistan, thus making the princes<strong>com</strong>pletely independent on 15 August. This would have led to the creation of a “ThirdDominion”, <strong>com</strong>prising confederations of princely states, and thereby throwing openpossibilities of some of the states going over to Pakistan, in “association”, if not“accession”. This book discusses some of the conspiracies hatched in that direction,which Patel scotched with rare boldness, backed by his towering personality that exudedunquestioning friendliness towards the princes. The states involved were major ones likeTravancore, Hyderabad, Junagadh, Jamnagar, and Jodhpur, and some Central Indianstates. Through his diplomatic manoeuvres, Patel secured “accession” of all states prior to15 August, before they could be made independent on par with India and Pakistan,thereby gaining equal status. The exceptions were those of Junagadh and Hyderabad—Kashmir too, but it was under Nehru’s charge.

On the ashes of a defunct empire, Patel created a New India—strong, united, put in asteel-frame. That frame was the Indian Administrative Service, which kept a subcontinentbound together as a single unit despite disparities of politics and economy. As saviourand builder, Patel played decisive roles that took India to new pinnacles of success andglory after centuries.Yet, the saviour and builder of New India was accused of responsibility for the partitionof India; and the assassination of Gandhi. Patel never asked for India’s partition. He andother Congress leaders were opposed to it. It was thrust upon them by the British throughAttlee’s policy statement of 20 February. He merely served India’s interests by makingpartition conditional upon division of Punjab and Bengal. He could not have left thePunjabi and Bengali Hindus, as well as the Sikhs, to the cruel mercies of the MuslimLeague after the genocide of August 1946 in Kolkata. He also looked beyond, in gaininga free hand in the integration of over 560 States.About Gandhi’s assassination, General Roy Bucher, the British <strong>com</strong>mander-in-chief ofthe Indian Army, wrote to the author in his letter of 24 July 1969: “From my knowledge,I am quite sure that Maulana Azad’s charge that Sardar Patel was responsible for themurder of the Mahatma was absolutely unfounded. At our meeting in Dehra Dun, theSardar told me that those who persuaded the Mahatma to suggest that monies (Rs. 55crore) held in India should be despatched to Pakistan were responsible for the tragedy,and that after the monies had been sent off, the Mahatma was moved up to be the first tobe assassinated on the books of a very well-known Hindu revolutionary society. Idistinctly remember the Sardar saying: ‘You know quite well that for Gandhiji to expressa wish was almost an order’.” It was on Gandhi’s insistence that security had beenwithdrawn.Gandhi <strong>com</strong>manded every Hindu’s veneration, Godse being no exception. He had bowedto him in reverence thrice before firing the shots. Gandhi had exhausted the patience ofeven Nehru and Patel over two of his impossible demands. First, asking Mountbatten, athis meeting on 1 April 1947, “to dismiss the present Cabinet [interim government] andcall on Jinnah to appoint an all-Muslim administration.” 2 This would have killed Patel’sdream of creating a unified India. He had publicly stated in 1939: “The red and yellowcolours on India’s map [representing provinces and states] have to be made one. Unlessthat is done, we cannot have swaraj.” 3 In Nehru’s case, Jinnah would have denied him thechance of be<strong>com</strong>ing independent India’s first prime minister—a historic opportunityNehru could not have missed under any circumstance.Gandhi’s second demand was even more difficult. Addressing the All-India CongressCommittee on 15 November 1947, he demanded that all Muslims who had fled Indiawere “to be called back and restored to peaceful possession and enjoyment of all that theyhad had, but been forced to abandon while running away”. 4 It would have amounted tomaking Hindu and Sikh refugees from Punjab and the NWFP vacate the Muslim housesthey had occupied by restoring the same to the Muslims who were living in refugeecamps the government had set up. It would have been a cruel double tragedy for thePunjabi refugees to suffer so soon after the Punjab genocide.

A year before Patel’s demise, M. N. Roy, once a <strong>com</strong>rade of Lenin in Soviet Russia and aCommunist of international fame, wrote: “What will happen to India when the masterbuilderwill go, sooner or later, the way of all mortals? . . . Nationalist India was fortunateto have Sardar Patel to guide her destiny for a generation. But her misfortune is that therewill be none to take his place when he is no more . . . when the future is bleak, onenaturally turns to the past, and Sardar Patel can be proud of his past.” 5 He was India’s“Iron Man”, who proved to be his country’s “saviour and builder”. Today’s India is whathe created and left behind.Some of Sardar Patel’s major achievements:1. Patel was the backbone of Gandhi’s satyagrahas. During the Dandi March in 1930, heplayed the role of John the Baptist to Gandhi as a forerunner who “baptised” people enroute. In a speech as Wasna, on his way to Dandi, Gandhi admitted: “I could succeed inKheda [in 1918] on account of Vallabhbhai, and it is on account of him that I am heretoday.”2. In the Bardoli satyagraha in 1928, Patel played the role of a Lenin. The British-ownedand edited Times of India wrote that Patel had “instituted there a Bolshevik regime inwhich he plays the role of Lenin”.3. As chairman of the Congress Parliamentary Board, Patel played the role of a strict bossin the conduct of the provincial elections in 1937. In that capacity he declared: “When theCongress roller is in action, all pebbles and stones will be levelled.” He did not sparesenior leaders like K. F. Nariman and N. B. Khare; not even the indomitable SubhashChandra Bose. He was an un<strong>com</strong>promising disciplinarian. That was a major contributionto the party’s unity and strength.4. Without Patel’s support Lord Wavell could not have formed the interim government inAugust 1946, nor could Lord Mountbatten, in 1947, have implemented transfer of powersmoothly and within the time-frame. In return, Patel got for India half of Punjab and halfof Bengal and the whole of Assam. Patel also got termination of paramountcy, whichenabled him to achieve integration of over 560 princely states. That was his masterstroke,which demolished Churchill’s imperial strategy. What was that strategy? Anaccount is given in the chapter A Churchillian Plan: Partition of India.5. Briefly discussed is what would have been India’s position in Kashmir, Tibet andNepal had Patel’s proposals been implemented. Kashmir had been taken away fromPatel’s charge by Nehru under Sheikh Abdullah’s pressure, while Tibet and Nepal wereforeign territories directly under Nehru’s charge.6. Philip Mason (ICS) has written in the Dictionary of National Biography: “Patel hasbeen <strong>com</strong>pared to Bismarck but the parallel cannot be carried far. Patel was courageous,honest and realistic, but far from cynical.”

7. On his demise on 15 December 1950, the Manchester Guardian (now Guardian)wrote: “Without Patel, Gandhi’s ideas would have had less practical influence andNehru’s idealism less scope.”My dear Jawaharlal,13COULD INDIA HAVE SAVED TIBET?Patel’s Historic Letter to NehruNew Delhi7 November 1950Ever since my return from Ahmedabad and after the Cabinet meeting the same day whichI had to attend at practically 15 minutes’ notice and for which I regret I was not able toread all the papers, I have been anxiously thinking over the problem of Tibet and Ithought I should share with you what is passing through my mind.I have carefully gone through the correspondence between the External Affairs Ministryand our Ambassador in Peking and through him the Chinese Government. I have tried toperuse this correspondence as favourably to our Ambassador and the ChineseGovernment as possible, but I regret to say that neither of them <strong>com</strong>es out well as a resultof this study. The Chinese Government have tried to delude us by professions of peacefulintentions. My own feeling is that at a crucial period they managed to instill into ourAmbassador a false sense of confidence in their so-called desire to settle the Tibetanproblem by peaceful means. There can be no doubt that during the period covered by thiscorrespondence the Chinese must have been concentrating for an onslaught on Tibet. Thefinal action of the Chinese, in my judgment, is little short of perfidy. The tragedy of it isthat the Tibetans put faith in us; they chose to be guided by us; and we have been unableto get them out of the meshes of Chinese diplomacy or Chinese malevolence. From thelatest position, it appears that we shall not be able to rescue the Dalai Lama. OurAmbassador has been at great pains to find an explanation or justification for Chinesepolicy and actions. As the External Affairs Ministry remarked in one of their telegrams,there was a lack of firmness and unnecessary apology in one or two representations thathe made to the Chinese Government on our behalf. It is impossible to imagine anysensible person believing in the so-called threat to China from Anglo-Americanmachinations in Tibet. Therefore, if the Chinese put faith in this, they must havedistrusted us so <strong>com</strong>pletely as to have taken us as fools or stooges of Anglo-Americandiplomacy or strategy. This feeling, if genuinely entertained by the Chinese in spite ofyour direct approaches to them, indicates that even though we regard ourselves as friendsof China, the Chinese do not regard us as their friends. With the Communist mentality of“whoever is not with them being against them,” this is a significant pointer of which wehave to take due note. During the last several months, outside the Russian camp, we havepractically been alone in championing the cause of Chinese entry into the UNO and insecuring from the Americans assurances on the questions of Formosa.We have done everything we could to assuage Chinese feelings, to allay itsapprehensions and to defend its legitimate claims in our discussions and correspondence

with America and Britain and in the UNO. In spite of this, China is not convinced aboutour disinterestedness; it continues to regard us with suspicion and the whole psychologyis one, at least outwardly, of skepticism, perhaps mixed with a little hostility. I doubt ifwe can go any further than we have done already to convince China of our goodintentions, friendliness and goodwill. In Peking, we have an Ambassador who iseminently suitable for putting across the friendly point of view. Even he seems to havefailed to convert the Chinese. Their last telegram to us is an act of gross discourtesy notonly in the summary way it disposes of our protest against the entry of Chinese forcesinto Tibet but also in the wild insinuation that our attitude is determined by foreigninfluences. It looks as though it is not a friend speaking in that language but a potentialenemy.In the background of this, we have to consider what new situation now faces us as a resultof the disappearance of Tibet, as we knew it, and the expansion of China almost up to ourgates. Throughout history we have seldom been worried about our north-east frontier.The Himalayas have been regarded as an impenetrable barrier against any threat from thenorth. We had a friendly Tibet which gave us no trouble. The Chinese were divided. Theyhad their own domestic problems and never bothered us about our frontiers. In 1914, weentered into a convention with Tibet which was not endorsed by the Chinese. We seem tohave regarded Tibetan autonomy as extending to independent treaty relationship.Presumably, all that we required was Chinese counter-signature. The Chineseinterpretation of suzerainty seems to be different. We can, therefore, safely assume thatvery soon they will disown all the stipulations which Tibet has entered into with us in thepast. That throws into the melting pot all frontier and <strong>com</strong>mercial settlements with Tibeton which we have been functioning and acting during the last half a century. China is nolonger divided. It is united and strong. All along the Himalayas in the north and northeast,we have on our side of the frontier a population ethnologically and culturally notdifferent from Tibetans or Mongoloids. The undefined state of the frontier and theexistence on our side of a population with its affinities to Tibetans or Chinese have all theelements of potential trouble between China and ourselves. Recent and bitter history alsotells us that <strong>com</strong>munism is no shield against imperialism and that the Communists are asgood or as bad imperialists as any other. Chinese ambitions in this respect not only coverthe Himalayan slopes on our side but also include important parts of Assam. They havetheir ambitions in Burma also. Burma has the added difficulty that it has no McMahonLine round which to build up even the semblance of an agreement. Chinese irredentismand Communist imperialism are different from the expansionism or imperialism of theWestern Powers. The former has a cloak of ideology which makes it ten times moredangerous. In the guise of ideological expansion lie concealed racial, national orhistorical claims. The danger from the north and north-east, therefore, be<strong>com</strong>es both<strong>com</strong>munist and imperialist. While our western and north-western threat to security is stillas prominent as before, a new threat has developed from the north and north-east. Thus,for the first time, after centuries, India’s defence has to concentrate itself on two frontssimultaneously. Our defence measures have so far been based on the calculations ofsuperiority over Pakistan. In our calculations we shall now have to reckon withCommunist China in the north and in the north-east, a Communist China which has

definite ambitions and aims and which does not, in any way, seem friendly disposedtowards us.Let us also consider the political conditions on this potentially troublesome frontier. Ournorthern or north-eastern approaches consist of Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, the Darjeeling[area] and tribal areas in Assam. From the point of view of <strong>com</strong>munications, they areweak spots. Continuous defensive lines do not exist. There is almost an unlimited scopefor infiltration. Police protection is limited to a very small number of passes. There, too,our outposts do not seem to be fully manned. The contact of these areas with us is by nomeans close and intimate. The people inhabiting these portions have no establishedloyalty or devotion to India. Even the Darjeeling and Kalimpong areas are not free frompro-Mongoloid prejudices. During the last three years we have not been able to make anyappreciable approaches to the Nagas and other hill tribes in Assam. Europeanmissionaries and other visitors had been in touch with them, but their influence was in noway friendly to India or Indians. In Sikkim, there was political ferment some time ago. Itis quite possible that discontent is smouldering there. Bhutan is <strong>com</strong>paratively quiet, butits affinity with Tibetans would be a handicap. Nepal has a weak oligarchic regime basedalmost entirely on force; it is in conflict with a turbulent element of the population as wellas with enlightened ideas of the modern age. In these circumstances, to make people aliveto the new danger or to make them defensively strong is a very difficult task indeed andthat difficulty can be got over only by enlightened firmness, strength and a clear line ofpolicy. I am sure the Chinese and their source of inspiration, Soviet Russia, would notmiss any opportunity of exploiting these weak spots, partly in support of their ideologyand partly in support of their ambitions. In my judgment, therefore, the situation is one inwhich we cannot afford either to be <strong>com</strong>placent or to be vacillating. We must have a clearidea of what we wish to achieve and also of the methods by which we should achieve it.Any faltering or lack of decisiveness in formulating our objectives or in pursuing ourpolicy to attain those objectives is bound to weaken us and increase the threats which areso evident.Side by side with these external dangers, we shall now have to face serious internalproblems as well. I have already asked [H. V. R.] Iengar to send to the E. A. Ministry acopy of the Intelligence Bureau’s appreciation of these matters. Hitherto, the CommunistParty of India has found some difficulty in contacting Communists abroad, or in gettingsupplies of arms, literature, etc. from them. They had to contend with the difficultBurmese and Pakistan frontiers on the east or with the long seaboard. They shall nowhave a <strong>com</strong>paratively easy means of access to Chinese Communists and through them toother foreign Communists. Infiltration of spies, fifth columnists and Communists wouldnow be easier. Instead of having to deal with isolated Communist pockets in Telenganaand Warangal we may have to deal with Communist threats to our security along ournorthern and north-eastern frontiers where, for supplies of arms and ammunition, theycan safely depend on Communist arsenals in China. The whole situation thus raised anumber of problems on which we must <strong>com</strong>e to an early decision so that we can, as I saidearlier, formulate the objectives of our policy and decide the methods by which thoseobjectives are to be attained. It is also clear that the action will have to be fairly<strong>com</strong>prehensive, involving not only our defence strategy and state of preparations but also

problems of internal security to deal with which we have not a moment to lose. We shallalso have to deal with administrative and political problems in the weak spots along thefrontier to which I have already referred.It is, of course, impossible for me to be exhaustive in setting out all these problems. I am,however, giving below some of the problems which, in my opinion, require early solutionand round which we have to build our administrative or military policies and measures toimplement them.a) A military and intelligence appreciation of the Chinese threat to India both on thefrontier and to internal security.b) An examination of our military position and such redisposition of our forces as mightbe necessary, particularly with the idea of guarding important routes or areas which arelikely to be the subject of dispute.c) An appraisement of the strength of our forces and, if necessary, reconsideration of ourretrenchment plans for the Army in the light of these new threats.d) Long-term consideration of our defence needs. My own feeling is that, unless weassure our supplies of arms, ammunition and armour, we should be making our defenceposition perpetually weak and we would not be able to stand up to the double threat ofdifficulties both from the west and north-west and north and north-east.e) The question of Chinese entry into UNO. In view of the rebuff which China has givenus and the method which it has followed in dealing with Tibet, I am doubtful whether wecan advocate its claims any longer. There would probably be a threat in the UNOvirtually to outlaw China in view of its active participation in the Korean War. We mustdetermine our attitude on this question also.f) The political and administrative steps which we should take to strengthen our northernand north-eastern frontiers. This would include the whole of the border, i.e. Nepal,Bhutan, Sikkim, Darjeeling and the tribal territory in Assam.g) Measures of internal security in the border areas as well as the States flanking thoseareas, such as UP, Bihar, Bengal and Assam.h) Improvement of our <strong>com</strong>munications, road, rail, air and wireless, in these areas andwith the frontier outposts.i) Policing and intelligence of frontier posts.j) The future of our mission at Lhasa and the trade posts at Gyangtse and Yatung and theforces which we have in operation in Tibet to guard the trade routes.k) The policy in regard to the McMahon Line.These are some of the questions which occur to my mind. It is possible that aconsideration of these matters may lead us into wider questions of our relationship withChina, Russia, America, Britain and Burma. This, however, would be of a general nature,though some might be basically very important, e.g. we might have to consider whetherwe should not enter into closer association with Burma in order to strengthen the latter inits dealings with China. I do not rule out the possibility that, before applying pressure onus, China might apply pressure on Burma. With Burma, the frontier is entirely undefinedand the Chinese territorial claims are more substantial. In its present position, Burmamight offer an easier problem for China and, therefore, might claim its first attention.

I suggest that we meet early to have a general discussion on these problems and decide onsuch steps as we might think to be immediately necessary and direct quick examinationof other problems with a view to taking early measures to deal with them.Yours,Vallabhbhai PatelPrime Minister Nehru’s Note on China and Tibet dated 18 November 1950[The note was obviously forwarded to Sardar Patel as it answered indirectly some of thematters raised in Sardar’s letter of 7 November 1950.]1. The Chinese Government having replied to our last note, we have to consider whatfurther steps we should take in this matter. There is no immediate hurry about sending areply to the Chinese Government. But we have to send immediate instructions to Shri B.N. Rau as to what he should do in the event of Tibet’s appeal being brought up before theSecurity Council or the General Assembly.2. The content of the Chinese reply is much the same as their previous notes, but theredoes appear to be a toning down and an attempt at some kind of a friendly approach3. It is interesting to note that they have not referred specifically to our mission [at]Lhasa or to our trade agents or military escort at Gyangtse etc. We had mentioned theseespecially in our last note. There is an indirect reference, however, in China’s note. At theend, this note says that “As long as our two sides adhere strictly to the principle of mutualrespect for territory, sovereignty, equality and mutual benefit, we are convinced that thefriendship between China and India should be developed in a normal way and thatproblems relating to Sino-Indian diplomatic, <strong>com</strong>mercial and cultural relations withrespect to Tibet may be solved properly and to our mutual benefit through normaldiplomatic channels.” This clearly refers to our trade agents and others in Tibet. We hadexpected a demand from them for the withdrawal of these agents etc. The fact that theyhave not done so has some significance.4. Stress is laid in China’s note on Chinese sovereignty over Tibet, which we arereminded, we have acknowledged, on Tibet being an integral part of China’s territory andtherefore a domestic problem. It is however again repeated that outside influences, havebeen at play obstructing China’s mission in Tibet. In fact, it is stated that liberation ofChangtu proves that foreign forces and influences were inciting Tibetan troops to resist. Itis again repeated that no foreign intervention will be permitted and that the Chinese armywill proceed.5. All this is much the same as has been said before, but it is said in a somewhatdifferent way and there are repeated references in the note to China desiring thefriendship of India

6. It is true that in one of our messages to the Chinese Government we used“sovereignty” of China in relation to Tibet. In our last message we used the word“suzerainty”. After receipt of the last China’s note, we have pointed out to ourAmbassador that “suzerainty” was the right word and that “sovereignty” had been usedby error.7. It is easy to draft a reply to the Chinese note, pressing our viewpoint and counteringsome of the arguments raised in the Chinese note. But before we do so we should be clearin our minds as to what we are aiming at, not only in the immediate future but from along-term view. It is important that we keep both these viewpoints before us. In allprobability China, that is present-day China, is going to be our close neighbour for a longtime to <strong>com</strong>e. We are going to have a tremendously long <strong>com</strong>mon frontier. It is unlikely,and it would be unwise to expect, that the present Chinese Government will collapse,giving place to another. Therefore, it is important to pursue a policy which will be inkeeping with this long-term view.8. I think it may be taken for granted that China will take possession, in a politicalsense at least, of the whole of Tibet. There is no likelihood whatsoever of Tibet beingable to resist this or stop it. It is equally unlikely that any foreign power can prevent it.We cannot do so. If so, what can we do to help in the maintenance of Tibetan autonomyand at same time avoiding continuous tension and apprehension on our frontiers?9. The Chinese note has repeated that they wish the Tibetan people to have what theycall “regional autonomy and religious freedom”. This autonomy can obviously not beanything like the autonomy verging on independence which Tibet has enjoyed during thelast forty years or so. But it is reasonable to assume from the very nature of Tibetangeography, terrain and climate, that a large measure of autonomy is almost inevitable. Itmay of course be that this autonomous Tibet is controlled by <strong>com</strong>munists alone in Tibet. Iimagine however that it is, on the whole, more likely that what will be attempted will be apro-<strong>com</strong>munist China administration rather than a <strong>com</strong>munist one.10. If world war <strong>com</strong>es, then all kinds of difficult and intricate problems arise andeach one of these problems will be inter-related with others. Even the question of defenceof India assumes a different shape and cannot be isolated from other world factors. I thinkthat it is exceedingly unlikely that we may have to face any real military invasion fromthe Chinese side, whether in peace or in war, in the foreseeable future. I base thisconclusion on a consideration of various world factors. In peace, such an invasion wouldundoubtedly lead to world war. China, though internally big, is in a way amorphous andeasily capable of being attacked on its sea coasts and by air. In such a war, China wouldhave its main front in the South and East and it will be fighting for its very existenceagainst powerful enemies. It is inconceivable that it should divert its forces and itsstrength across the inhospitable terrain of Tibet and undertake a wild adventure across theHimalayas. Any such attempt will greatly weaken its capacity to meet its real enemies onother fronts. Thus I rule out any major attack on India by China. I think theseconsiderations should be borne in mind, because there is far too much loose talk aboutChina attacking and overrunning India. If we lose our sense of perspective and world

strategy and give way to unreasoning fears, then any policy that we might have is likelyto fail.11. While there is, in my opinion, practically no chance of a major attack on India byChina, there are certainly chances of gradual infiltration across our border and possibly ofentering and taking possession of disputed territory, if there is obstruction to thishappening. We must therefore take all necessary precautions to prevent this. But, again,we must differentiate between these precautions and those that might be necessary tomeet a real attack.12. If we really feared an attack and had to make full provision for it, this would castan intolerable burden on us, financial and otherwise, and it would weaken our generaldefence position. There are limits beyond which we cannot go, at least for some years,and a spreading out of our army on distant frontiers would be bad from every military orstrategic point of view.13. In spite of our desire to settle the points at issue between us and Pakistan, anddeveloping peaceful relations with it, the fact remains that our major possible enemy isPakistan. This has <strong>com</strong>pelled us to think of our defence mainly in terms of Pakistan’saggression. If we begin to think of, and prepare for, China’s aggression in the same way,we would weaken considerably on the Pakistan side. We might well be got in a pincermovement. It is interesting to note that Pakistan is taking a great deal of interest, from thepoint of view, in developments in Tibet. Indeed it has been discussed in the PakistanPress that the new danger from Tibet to India might help them to settle the Kashmirproblem according to their wishes. Pakistan has absolutely nothing in <strong>com</strong>mon withChina or Tibet. But if we fall out <strong>com</strong>pletely with China, Pakistan will undoubtedly try totake advantage of this, politically or otherwise. The position of India thus will be badfrom a defence point of view. We cannot have all the time two possible enemies on eitherside of India. This danger will not be got over, even if we increase our defence forces oreven if other foreign countries help us in arming. The measure of safety that one gets byincreasing the defence apparatus is limited by many factors. But whatever that measure ofsafety might be, strategically we would be in an unsound position and the burden of thiswill be very great on us. As it is, we are facing enormous difficulties, financial,economic, etc.14. The idea that <strong>com</strong>munism inevitably means expansion and war, or to put it moreprecisely, that Chinese <strong>com</strong>munism means inevitably an expansion towards India, israther naïve. It may mean that in certain circumstances. Those circumstances woulddepend upon many factors, which I need not go into here. The danger really is not frommilitary invasion but from infiltration of men and ideas. The ideas are there already andcan only be countered by other ideas. Communism is an important element in thesituation. But, by our attaching too great importance to it in this context, we are likely tomisjudge the situation from other and more important angles.15. In a long-term view, India and China are two of the biggest countries of Asiabordering on each other and both with certain expansive tendencies, because of their

vitality. If their relations are bad, this will have a serious effect not only on both of thembut on Asia as a whole. It would affect our future for a long time. If a position arises inwhich China and India are inveterately hostile to each other, like France and Germany,then there will be repeated wars bringing destruction to both. The advantage will go toother countries. It is interesting to note that both the UK and the USA appear to beanxious to add to the unfriendliness of India and China towards each other. It is alsointeresting to find that the USSR does not view with favour any friendly relationsbetween India and China. These are long-term reactions which one can fully understand,because India and China at peace with each other would make a vast difference to thewhole set-up and balance of the world. Much of course depends upon the development ofeither country and how far <strong>com</strong>munism in China will mould the Chinese people. Even so,these processes are long-range ones and in the long run it is fairly safe to assume thathundreds of millions of people will not change their essential characteristics.16. These arguments lead to the conclusion that while we should be prepared, to thebest of our ability, for all contingencies, the real protection that we should seek is somekind of understanding of China. If we have not got that, then both our present and ourfuture are imperilled and no distant power can save us. I think on the whole that Chinadesires this too for obvious reasons. If this is so, then we should fashion our presentpolicy accordingly.17. We cannot save Tibet, as we should have liked to do, and our very attempts to saveit might well bring greater trouble to it. It would be unfair to Tibet for us to bring thistrouble upon her without having the capacity to help her effectively. It may be possible,however, that we might be able to help Tibet to retain a large measure of her autonomy.That would be good for Tibet and good for India. As far as I can see, this can only bedone on the diplomatic level and by avoidance of making the present tension betweenIndia and China worse.18. What then should be our instructions to B. N. Rau? From the messages he has sentto us, it appears that no member of the Security Council shows any inclination to sponsorTibet’s appeal and that there is little likelihood of the matter being considered by theCouncil. We have said that [we] are not going to sponsor this appeal, but if it <strong>com</strong>es upwe shall state our viewpoint. This viewpoint cannot be one of full support of the Tibetanappeal, because that goes far and claims full independence. We may say that whatevermight have been acknowledged in the past about China’s sovereignty or suzerainty,recent events have deprived China of the right to claim that. There may be some moralbasis for this argument. But it will not take us or Tibet very far. It will only hasten thedownfall of Tibet. No outsider will be able to help her and China, suspicious andapprehensive of these tactics, will make sure of much speedier and fuller possession ofTibet than she might otherwise have done. We shall thus not only fail in our endeavourbut at the same time have really a hostile China on our doorstep.19. I think that in no event should we sponsor Tibet’s appeal. I would personally thinkthat it would be a good thing if that appeal is not heard in the Security Council or theGeneral Assembly. If it is considered there, there is bound to be a great deal of bitter

speaking and accusation, which will worsen the situation as regards Tibet, as well as thepossibility of widespread war, without helping it in the least. It must be remembered thatneither the UK nor the USA, nor indeed any other power is particularly interested inTibet or the future of that country. What they are interested in is embarrassing China. Ourinterest, on the other hand, is Tibet, and if we cannot serve that interest, we fail.20. Therefore, it will be better not to discuss Tibet’s appeal in the UN. Suppose,however, that it <strong>com</strong>es up for discussion, in spite of our not wishing this, what then? Iwould suggest that our representative should state our case as moderately as possible andask the Security Council or the Assembly to give expression to their desire that the Sino-Tibetan question should be settled peacefully and that Tibet’s autonomy should berespected and maintained. Any particular reference to an article of the Charter of the UNmight tie us up in difficulties and lead to certain consequences later, which may provehighly embarrassing for us. Or a resolution of the UN might just be a dead letter whichalso will be bad.21. If my general argument is approved, then we can frame our reply to China’s noteaccordingly.J. Nehru18 November 1950