Classic Process Excellence: the Dabbawala System

Posted: March 16, 2014 Filed under: Performance improvement | Tags: dabbawala, lean, Lean Six Sigma, lean thinking, lunch boxes, Mumbai, six sigma, supply chain, supply chain management, tiffin Leave a commentFor process excellence practitioners the dabbawalas of Mumbai are one of the great case studies of a lean, low-capital, virtually defect-free (better than 6.0 sigma) service-logistics process. The group has become so famous that they are regularly invited to present their way of working to Global Fortune 100 companies. For those unfamiliar with what the dabbawala do, here is a quick snapshot:

- A dabbawala (one who carries the box) is a person in the Indian city of Mumbai whose job is to carry and deliver freshly made food from home in lunch boxes to office workers. Tiffin is an old-fashioned English word for a light lunch, and sometimes for the box itself.

- There are about 5,000 dabbawallas who ferry over 200,000 home-cooked meals from the outer suburbs into the city each day.

- The dabbawallahs date back to the late 19th century when Bombay’s rapidly growing population needed feeding at work. More than a century later many of Mumbai’s middle classes still prefer their meals hot and home-cooked.

The process is rightly admired for its low-tech methods. No less than Professor C.K. Prahalad of the University of Michigan Business School believes the dabbawallahs offer a near-perfect case study of the principles of supply chain management.

“Six sigma essentially means you can make no errors,” says Prahalad. “One-hundred and seventy-five thousand boxes are transported every day, it has to go to the right person, it has to start from a point of origination, go through trans-shipment in the infrastructure which is the public infrastructure in the trains of Mumbai in all seasons including the monsoon and it has to arrive on time in the right place in the right box.” “I think logistics is becoming more and more a top management issue,” said Prahalad. “That’s a good thing by itself because you can dramatically reduce the capital intensity of a business. A lot of the float there is between points of production and consumption can be reduced dramatically around the world.”

The Dabbawallah Foundation, in describing the system on own website (http://www.dabbawala.in/index.php#), write:

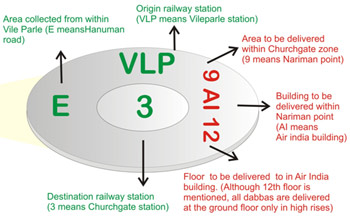

The success of the system depends on teamwork and time management that would be the envy of a modern manager. Such is the dedication and commitment of the barely literate and barefoot delivery men who form links in the extensive delivery, that there is no system of documentation at all. A simple colour coding system doubles as an ID system for the destination and recipient. There are no multiple elaborate layers of management either — just three layers.

I think their description starts to get at some of the most important aspects of the dabbawalla approach and that are keys to achieving and sustaining breakthrough performance:

- There is a de facto empowerment of the frontline rather than on a layer of senior executives at a headquarter to direct them;

- Information is encoded in the process itself (much as kanban cards transmit information automatically as a by-product of people working the process) through colour-coded containers;

- While technology is not deliberately avoided, nor is it made the focus; the basic underlying process is made sound and technology (in the form of bicycles or text messaging) is used only where it enhances the process (affordably) as opposed to taking the limelight (a problem many executives have, as enamored of their iPads and other gadgets);

- A few simple rules can create and manage a complex system and yet the system is highly resilient because of the de-centralized nature of its controls and the simplicity of its rules; if a single executive or a team of MBAs sitting in corporate headquarters tried to manage this complex web they would find it exponentially more difficult and they would induce more risk and fragility.

The process itself was described in this article by rediff.com:

- The process begins early in the morning. Cooked food is picked up from houses and caterers by dabbawallahs and taken to the nearest railway station.

- Tiffin boxes are sorted out for specific destination stations and loaded on to large, rectangular trays accordingly.

- Each tray can hold up to 40 boxes. These trays then travel in local trains down to various stations. At each station, there are another set of dabbawallahs who quickly take the dabbas meant to be distributed in that area and push in dabbas meant for other stations.

- A Mumbai local train halts at a station for about 20 seconds or less and thus, the dabbawallahs have to work with precision and speed. During rush hour, it’s a nightmare.

- At each station, the boxes are once more sorted for localities and offices and taken there by hand carts or sometimes carried by individuals. “We carry up to 35 kg for distances of a couple of kilometers,” points out Medge.

- The boxes are placed in the offices’ reception area by 12.30 pm and are picked up from the same spot by the deliverer a couple of hours later.

- The whole process then starts again in the reverse. The boxes are picked up from the offices, taken to the nearest station and sorted for their journey home.

- Forbes magazine gave this service its highest quality rating of Sigma 6, which means that per million transactions, there is just an error of one. The service runs every working day.

“Every day, we deliver 175,000 to 200,000 lunch boxes,” said Medge. “We use colours and code markings to ensure faultless delivery.” These codes would baffle a cryptographer! But they make perfect sense to the dabbawallahs. The codes and colours indicate the place from where a dabba is collected; the station where it must be unloaded and the office it is to be delivered. Explaining one part of the code, Medge said they use English alphabets to mark out stations — such as A for Andheri and Bo for Borivli.

The men who form part of the organisation are not employees. “If you have employees, then you have unions and strikes,” said Medge, revealing his deep business acumen. “We are all shareholders in the Trust and we thus share in the earnings.” On an average, a dabbawalla can make about Rs 3,000 to 5,000. The Trust provides several services to its members, including schools for the children and health care in emergencies. What makes the dabbawallahs an extremely tight-knit group is that they all hail from the same region, Pune district in Maharashtra. “We all come from the region east of the Sahyadri [Western Ghats], and everyone who joins us is known to us,” said Medge. “If an outsider does join in, we initially employ him on a fixed salary, and if in a couple of years he wins our trust, we may make him a shareholder,” added Medge.