We have just celebrated the 153rd birth anniversary of “Mahatma” or, more ordinarily, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

There are question on the minds of many — Is the era of the Mahatma over? This question pertains not only to those who, whether in India or around the world, have come to dislike Gandhi, but also to those who have forgotten him altogether.

This visceral or unspoken distaste not just for Gandhi but all possible Mahatmas, or great souls, is certainly the mark of an age which is deeply suspicious, to recall the famous title of Thomas Carlyle’s book, of heroes and hero-worship.

Let us leave aside the well-worn clichés of the familiar Gandhi-haters: Gandhi emasculated Hindus with his absurdly impractical philosophy of non-violence; Gandhi caused the Partition of India by not standing up strongly enough against separatist forces; Gandhi’s rejection of modern, industrial civilisation would have driven India back to the middle ages; Gandhi’s idea of self-sufficient village republics was utopian and unworkable; Gandhi’s failing unequivocally to condemn the caste system or the patriarchy made him a traditionalist rather than reformist; Gandhi’s publicly avowed abstinence was flawed; Gandhi’s belief in the voice of his conscience was irrational; Gandhi’s almost mesmerising sway over the Indian masses and his charismatic leadership of a nation of 300 million turned him into a dangerous demagogue; Gandhi’s favouring Jawaharlal Nehru over both Subhas Chandra Bose and Vallabhbhai Patel was the root cause of most of the later failures of India. And so on.

The list can go on and on. In my own book, The Death and Afterlife of Mahatma Gandhi (2015), I said that Gandhi was the man we most hate to love and love to hate. In recent times, Gandhi-bashing has reached an unprecedented ferocity.

His statues abroad have come under attack and back in India, social media was rife with Gandhi-hatred, especially on his birthday. The bottom line of all this propaganda, some puerile, much motivated, may be subsumed under one major common theme — the inability to understand Gandhi.

So great a challenge does Gandhi pose, so baffling is he even to the best of minds, that we tend to pigeonhole him into some artificial stereotype or the other. At the root of these misunderstandings is taking his words out of context, not being able to see Gandhi as very much a product of his times, not just as a trans-historical and paradigmatic change-agent.

As a person in his own day and time, he, like others, made mistakes. For example, one might draw a connecting line from his misjudgement in supporting the reactionary Khilafat Movement in 1919 to the Partition of the subcontinent in 1947.

But the fact remains that all attempts completely to de-platform Gandhi have failed. As have endeavours to substitute him with some other figure — whether V. D. Savarkar or B.R. Ambedkar, to name two familiar antagonists — as putative Fathers of the Nation.

The persistence of Gandhi remains one of the enduring paradoxes of our times. Today, when there is talk in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) circles of Akhand Bharat or undivided India, the eerie silence around the missing Mahatma in some of these conversations becomes all the more deafening.

For uniting the subcontinent through conquest or force seems like a pipe dream. Only a union of hearts and minds can make us move in that direction. That is where Gandhi re-enters the world stage. That is because when it comes to dividing people and encouraging conflicts between them, there may be a hundred other useful mascots.

But when it comes to the politics and pragmatics of non-violent coexistence, even friendship, between those divided by generations of mistrust and bitterness, we must re-turn to Gandhi.

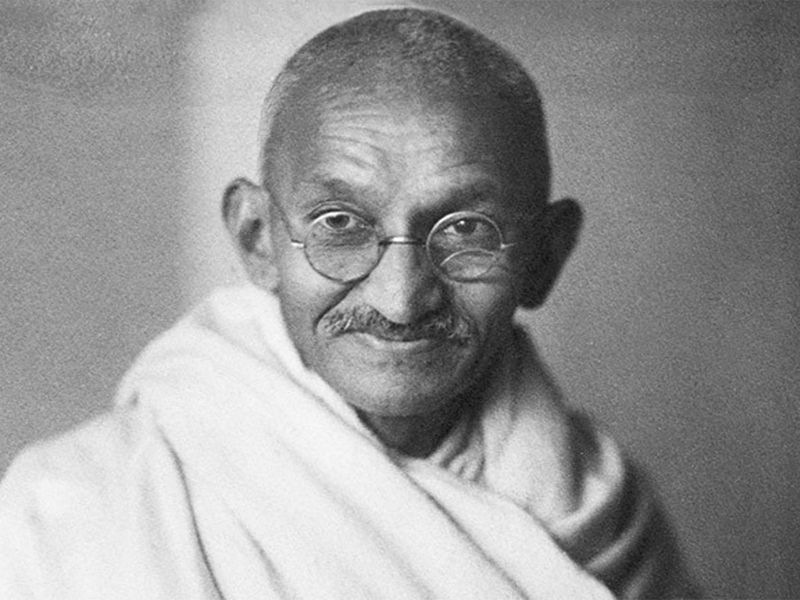

The moment we renounce violence and substitute it with love, Gandhi shows us the way. While others may teach us to kill for our beliefs, only Gandhi teaches us to give up our lives to defend the very conscience of humanity. He shows us how to face up to even the most hardened and monstrous of adversaries.

Gandhi’s undying faith in the innate goodness of humanity, his relentless pursuit of truth and ahimsa (non-injury to others), and his striving for swaraj or an enlightened polity make him indispensable to human social evolution. A stress on both private and public morality as well as striving for equality and justice for all were the keynotes of a life extraordinary by any standards.

In the face of a new admiration for violence as a useful political tool, not to speak of the rise of the cancel culture and global intolerance, it certainly seems as if the era of the Mahatma is over. Those who knew the Mahatma, walked with him, lived by his ideals and principles are now all gone.

His numerous experiments, organisations, and institutions are all in a state of decay. His ashram vows — non-violence, truth, non-stealing, non-possession, control of the palate, fearlessness, equal regard for all religions, Swadeshi and removal of untouchability — all sound irrelevant.

But, as Raja Rao says in Mahatma Gandhi: The Great Indian Way, “When the sea and the waves are seen as water you see greatness. Greatness is not great. It is.” Yes, the age of the Mahatma is over, but the return of Gandhi, the man, is inevitable.