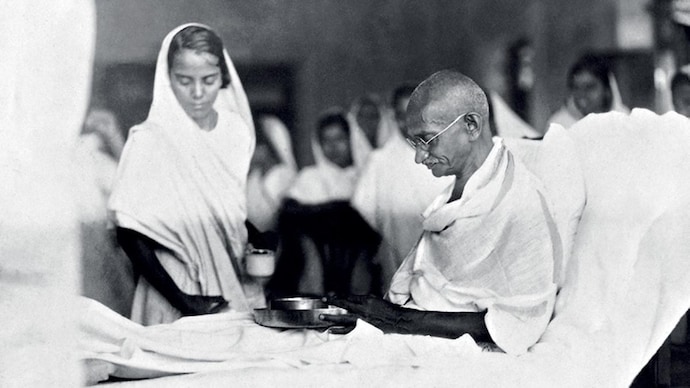

Mahatma Gandhi's experiments with food

Gandhi's eating habits were intimately connected to his politics.

In February 1929, African-American scientist George Washington Carver outlined a special diet involving whole wheat flour, corn, fruit and milk made from either soybeans or peanuts. With this vegan diet, Carver hoped to bring "greater health, strength and economic independence to India". Could a diet really achieve such grand ambitions? The intended recipient of Carver's diet certainly thought so. Like Carver, Mahatma Gandhi was a passionate food reformer who believed that eating right was central to living right, that a good diet was as much about politics and ethics as about nutrition.

However, aligning his culinary choices with his other beliefs was not always easy. Indeed, part of the appeal of Carver's diet was that Gandhi had, for years, struggled to become vegan. He believed consuming milk was unethical, but found that eliminating it from his diet left him weak and unable to respond to the many demands of his life. Could peanut milk prepared by a former slave help Gandhi resolve his lifelong search for the perfect diet?

When I started studying Gandhi's diet, I was interested in two questions: what did food mean to Gandhi? And what could I learn from his culinary and nutritional experiments? Here was a man who was extraordinarily busy and yet found time to author scores of articles, letters and speeches on questions of diet. He offered food advice to friends and strangers and eagerly devoured (forgive the pun) the latest research on the science of nutrition. What could he teach us now about how to eat and how to live?

The first thing that struck me was how Gandhi anticipated so many of today's dietary preoccupations-from veganism and whole grains, to raw food and fasting. Eliminating salt and sugar from his diet, foraging for wild greens and making his own almond milk, Gandhi seemed more like a poster-child for foodies now than the radical anticolonial activist I had studied as a child. But as I delved deeper into the history of Gandhi's relationship with food, I realised that his diet was intimately connected to his politics. For Gandhi, eating ethically meant more than avoiding certain foods; it meant connecting what we eat to the struggle against injustice and inequality.

Consider his vegetarianism. Gandhi was born into a vegetarian family. As a young man, he came to believe that eating meat had allowed the English to conquer India. If he was going to grow strong, he reasoned, he would have to eat meat too. Secretly, he sampled a few bites of goat meat. That night, he had a nightmare. "Every time I dropped off to sleep," he later recalled, "it would seem as though a live goat were bleating inside me, and I would jump up full of remorse."

Before beginning his legal studies in London, Gandhi promised his mother that he would not touch "wine, women and meat". In England, he came to truly believe in vegetarianism for the first time in his life. Although he had avoided meat for most of his childhood, it was only in London that he embraced ethical reasons to not eat meat. In the process, he found his first political cause: vegetarianism. As a member of the London Vegetarian Society, Gandhi overcame his fear of public speaking and became, for the first time, an activist championing a cause. Or rather, he became an activist championing a range of causes. The vegetarian community attracted social reformers of many kinds, and Gandhi learned to link his vegetarianism to a series of radical causes and to an expansive conception of non-violence.

Gandhi was not satisfied with merely rejecting meat. As his belief in vegetarianism deepened, he grappled with whether he should forego not just meat but also eggs and milk. Ultimately, he became convinced that he should become vegan. But giving up milk proved much harder than abstaining from meat. For decades, he tried to find a vegan equivalent to milk. By the time Carver prepared his recipe for peanut milk, Gandhi had already perfected his own homemade almond milk. But nut milks proved unsatisfying, perhaps because they were hard for him to digest. Eventually, Gandhi did something quite un-Gandhian-he revised a vow. He had vowed to never drink milk, but decided that his vow did not include goat's milk. From goat meat to goat's milk, Gandhi's vegetarian path was winding, often frustrating, but ultimately revealing of one of the greatest lessons of his lifelong struggles with food: that no one can achieve the perfect diet.

Gandhi practised many of today's most popular dietary principles, especially calorie restriction and a diet high in fruits, vegetables and nuts. His personal and spiritual growth were deeply connected to his dietary growth. His experiments with his diet have a lot to teach us, but that doesn't mean that they can be reduced to simple lessons. Gandhi would have been either amused or disgusted-or perhaps both-by the tendency of food pundits to offer simple solutions to all dietary questions. Gandhi changed his mind repeatedly. He struggled with his diet-and those struggles became as fascinating to me as his dietary triumphs.

His dietary and political struggles were interlinked. He praised salt as a young man, rejected it entirely in the middle of his life and then turned to moderation as he aged. His preoccupation with salt explains one of his most renowned acts of civil disobedience. He might never have conceived of a 'Salt March' if he had not been obsessed for decades with how much salt to add to his own food.

His interest in raw food and wild food, similarly, was both nutritional and political. He repeatedly experimented with eating nothing but uncooked food, or what he called "vital food", because it appealed to his love for simplicity. In addition, he believed that nutrients were lost in the process of cooking. "Vitamin A is destroyed by the mere applying of heat," he wrote. But his love for raw, wild greens also stemmed from his hope that India's rural poor could find sustainable and affordable sources of nutrition.

Part of what drove my initial interest in Gandhi's diet was my hope that I would learn lessons I could apply in my own kitchen. I failed to interest my wife or children in Gandhi's raw food diet. I shouldn't have been surprised: Gandhi himself usually included some cooked food in his diet. One of his favourites is a staple in my home as well: porridge. Whereas we tend to make ours with oatmeal, Gandhi preferred a whole wheat porridge that he made from scratch. His passion for whole grains is one of the easiest Gandhian dietary precepts to follow in our world.

What is the hardest? That depends on one's own dietary constraints and one's taste buds. I find it relatively easy to cut back on salt-although I have never tried, like Gandhi, to abstain entirely. I prefer fruit to most processed sweets and so am not too troubled by Gandhi's rejection of refined sugar (although when offered dark chocolate, I tend to conveniently forget Gandhi's statement that there is "death in chocolates"). For me, the greatest struggle is to eat less. In addition to regularly fasting, Gandhi was a master of portion control. While his obsession with controlling his food intake was often excessive, those of us who have the opposite problem can learn from the many strategies Gandhi employed to eat less. Did he really need such strategies? I used to think it was easy for Gandhi to abstain from eating. But contrary to his ascetic image, Gandhi loved food. That is part of why his search for the perfect diet is so relatable-it wasn't easy for him to live up to his own dietary ideals.

At his best, Gandhi connected his dietary passion to his struggles to create a better world. In 1942, with the world engulfed in war, he received a series of writings from Carver, hand-delivered by a doctor visiting from the US. Gandhi jokingly told him that he would receive the writings only from Carver himself. After being informed that Carver was too sick to travel, Gandhi initiated a pointed conversation.

Gandhi: "But even this genius suffers under the handicap of segregation, does not he?"

Doctor: "Oh yes, as much as any Negro."

Gandhi: "And yet these people talk of democracy and equality! It is an utter lie."

Doctor: "But Dr Carver is never bitter or resentful."

Gandhi: "I know, that is what we believers in non-violence have to learn from him."

As we recognise the 150th anniversary of Gandhi's birth, it is fitting to ask what we can learn from Gandhi, his legacy, and his diet. As his praise for Carver makes clear, Gandhi himself learned from many people, as well as from his own mistakes. His diet was a form of connection. Perhaps that is the greatest lesson of Gandhi's diet. In our struggles to eat right and to live right, we are never alone.

Nico Slate is a professor of history at Carnegie Mellon University and the author of Gandhi's Search for the Perfect Diet: Eating with the world in mind and Lord Cornwallis is Dead: The struggle for democracy in the United States and India.